'It was an act of principle': The Covid doctor who quit over Cummings

On 24 May, a couple of days after it was revealed that Dominic Cummings had travelled to Durham during the lockdown, a British cardiologist, Dr Dominic Pimenta, published a tweet in which he threatened to resign if Cummings did not. For Pimenta, news of Cummings’s trip had landed like a blow. In March, he had been drafted on to a Covid-19 intensive care unit, where he had witnessed suffering and death, struggle and recovery: “This sheer volume of human capacity that had been devoted to trying to save lives.” His tweet came at the end of a terrible weekend of intensive care shifts, during which he had watched patients die, their loved ones absent, and he had given everything of himself and seen colleagues do the same. And now this? “If we are going to be asked to risk our lives,” he wrote later, “the least we can expect is to be treated like people.”

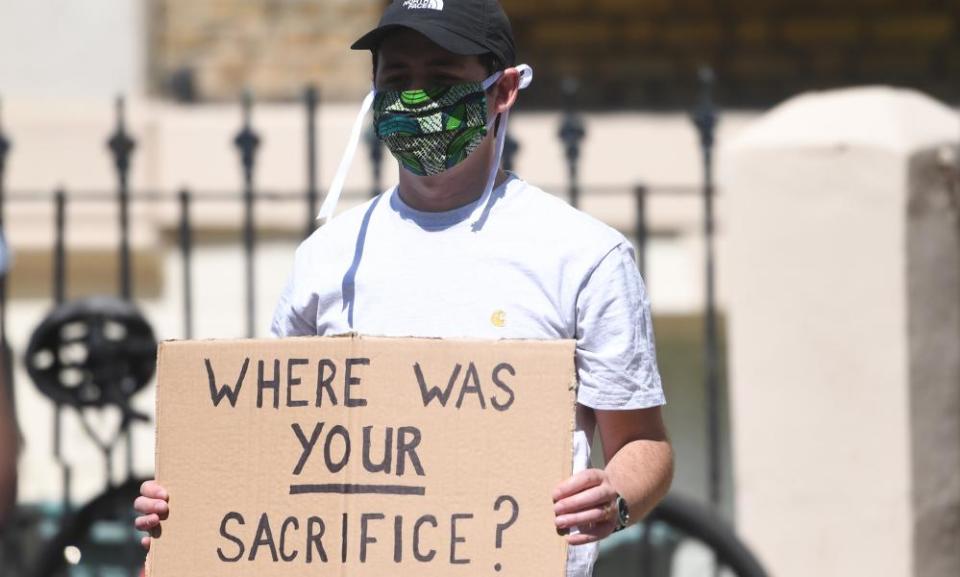

Pimenta’s tweet was widely shared. By the following morning he’d become a national news story, and he was invited by the media to share more of what he wanted to say: how he hoped that by making a stand he might highlight the recent sacrifices of healthcare workers while reassuring the public that their own sacrifices had not been in vain, that the lockdown was saving lives, that they must maintain faith in it. Catherine Calderwood, Scotland’s former chief medical officer, had recently resigned for a minor lockdown transgression. Pimenta wanted Cummings to do the same, or to at least acknowledge how irresponsible he’d been. “It was an act of principle,” Pimenta says. “And the principle was: this isn’t acceptable, I will not accept it. All I ever wanted was for the government to underline the importance of the lockdown.”

On social media, strangers congratulated Pimenta for making a stand. But much of the reaction he received was negative. People asked, How could he quit now, in the middle of a pandemic? Wasn’t he letting others down? He had hoped his superiors might make a stand, but nobody did. So when he was asked why he felt this was his responsibility, he replied: “If not me, then who?” He thought: “If everyone accepts this, then it becomes acceptable.” In medical school, he had been encouraged to speak up whenever he felt something was wrong. And maybe he took this too personally, he admits, but he considered making a stand a moral obligation. “There was almost a duty of public health to draw attention to the fact that this was not OK,” he says. “There had to be a line.”

When Pimenta realised that Cummings had no intention of handing in his notice, and that the government would not force him to, he understood what had to come next. His family was supportive, but apprehensive. His colleagues were mostly confused. What would he do now? He could still work as a doctor, but giving up his cardiology post meant significantly stalling his career – would it ever recover? He had had no intention of resigning before the pandemic, and yet here he was. When he handed in his notice, he agreed he would continue to work in the intensive care unit until October, by which point, he hoped, the coronavirus would have been contained and many of the patients he was caring for would have recovered. After that, he would be free to do something else.

Pimenta is 33, with dark hair shaved close to the scalp. We are meeting in his north London garden, while his sister cares for his young children, to discuss these past few months: the controversial decisions he has made, the decisions that turned him into a quasi celebrity and led to his resignation.

On the morning of 28 February, long after the coronavirus had escaped Wuhan and spread to other parts of the world, but before life in the UK began to change inconceivably, Pimenta published an urgent opinion piece on the Huffington Post in which he described Covid-19 as “a spectre on the horizon”, shared terrifying national infection estimates, and requested that the UK government act more decisively to ensure the NHS was prepared for the coming storm: more intensive care beds, more staff, immediate containment measures. Britain had yet to enforce lockdown – it wouldn’t do so until 23 March, despite confirmed cases in the UK as early as January – and even with significant warning, government reaction seemed sluggish. “Everybody kept saying, in that typically British way, ‘The NHS is ready,’” Pimenta says, “and I was like: ‘It’s really not!’”

If we’d been able to cope, it all would have been avoidable

He had watched with morbid fascination when Covid-19 first appeared in China, and then with terror and awe as it raged across the world. Soon, the bad news came in an endless flow. Pimenta’s wife, Dilsan, is also a doctor, and they began sharing emerging research with increasing frequency. It did not paint a pretty picture. A week before Pimenta published his opinion piece, while the pair sat at their kitchen countertop eating soup to stave off the February cold, Dilsan shared worrying news.

“It’s in Italy now,” she said.

Both of them sat sullen.

“If it can happen in Italy, why not here?”

The news came as “an explosion”, Pimenta says. What was once “a distant earthquake” had suddenly moved much closer. They watched as Italy was torn apart – the overloaded intensive care units, the shocking number of body bags, the confusion and terror and tragedy. Pimenta was troubled. At work, a large London teaching hospital, his colleagues discussed the coronavirus anxiously, aware it was coming if not already silently among them. But they seemed prevented by procedure to put into place measures that would contain the spread. Until mid-March, hospital guidelines restricted Pimenta from testing patients for coronavirus unless they had recently travelled to affected areas, even though the virus was known to be already out in the community. Pimenta struggled to understand why more action wasn’t being taken. Once, when he suggested replacing face-to-face appointments with phone consultations to reduce contact, he was overruled. He spoke to doctors at other London hospitals who had been asked by management to remove their masks because the sight of them panicked patients, placing their health at risk. (Some later contracted the virus.) He found that though many of his superiors appeared worried, others were blasé, driven by “a combination of naivety and optimism”, and unable to face an uncomfortable truth. Worse, the seriousness of the situation had yet to sink in at government level, Pimenta thought, and the trickle-down effects of its inactivity meant that the danger hadn’t fully permeated the public consciousness. The atmosphere in the hospital, as well as in public spaces he still visited, was one of inertia. Often, a kind of wait-and-see attitude prevailed.

Pimenta began to return home from work in a funk. He was unable to sleep. He thought: “Shouldn’t we be doing more? Why aren’t we preparing?” Anxious, he recorded observations on his way to and from the hospital. Just before he published his opinion piece, he noted: “There are now two obvious and inescapable truths. That the virus can no longer be contained, because we aren’t testing or finding contacts anymore, and that without widespread measures it will continue to double every two to three days. And yet still nothing changes.”

As soon as Pimenta published that first opinion piece, he was roundly described as sensationalist and irresponsible, both on social media, by strangers, and at work, by many of his hospital colleagues. His co-workers thought he was inciting panic unnecessarily. “A lot of them thought, ‘Why is it you that’s saying this? What right do you have?’” Colleagues asked: “Isn’t there someone up the chain who should speak out instead?” Because Pimenta is active on Twitter, he began to be labelled a “media doctor”. People questioned his ambitions, as though he were using his medical position as a platform to celebrity. Was he performing his duty? Or was he self-promoting? Pimenta was undeterred. “I just kept doing the numbers,” he says. “OK, if we have this many cases one week, then we’ll have double the week after, and so on and so on. All I could see was that this was going to get much, much worse. And people would say: ‘Oh no, that won’t happen.’ But nobody could actually prove to me that it wouldn’t!”

In the middle of March, Pimenta appeared on Channel 4 News to reassert his opinion that government should enforce a national lockdown as quickly as possible in order to contain the virus. By then, the UK had recorded 53 Covid-19-related deaths, according to the World Health Organisation, and confirmed case numbers were soaring. Other countries had shut down already. But again his appearance was described as attention-seeking and alarmist, even though prominent scientists, including Sir Patrick Vallance, the government’s Chief Scientific Adviser, had suggested doing the same. At work, he became “horribly isolated”. Weeks later, he resigned.

In June, Pimenta started writing a book. He had been approached by a publisher to write an account of his personal experience on the frontline of the pandemic: about those anxious early days, when the wave was coming but nobody seemed prepared; about life in a Covid-19 intensive care unit; about his resignation. When he started writing, he looked back through the notes he had jotted down as the coronavirus spread and then, to help with chronology, at his Twitter feed, which he used throughout the first wave like a personal blog, and which threw up the raw emotion of the past few months.

Pimenta’s book, Duty of Care, is a startlingly personal account. It can be described as a memoir, a thriller or a horror story, but really it is all at once. He thinks of the book as a corrective. “For lots of people, lockdown was this intangible inconvenience. You just stayed at home until you were told not to. You didn’t see it. But we did. We saw the wave hit. We saw people sicker than we’ve ever seen – a huge loss of life. And what I worry about is this whole episode has gone undercover. The ITUs were closed. Relatives couldn’t visit.” He hopes that by describing his own experience, the book will provide “an idea of what it was like, what it achieved, what your sacrifice achieved”.

Pimenta will receive a writer’s fee for the book, but its royalties will be donated to Heroes, a charity he set up in March in response to the UK’s critical shortage of PPE. Heroes has since developed into a support network for the welfare and wellbeing of NHS workers, partly because Pimenta is concerned about the long-term emotional toll the outbreak will have on them – the pressure and agony of the situation, of so often being helpless while patients suffer. A recent Chinese study found that front-line nurses in Wuhan experienced “a variety of mental health challenges, especially burn-out and fear”. He fears a similar wave will hit the NHS. “One of the drivers of PTSD is being out of control,” he says, so “there’s going to be a massive toll on people who felt dumped in it. Everybody, to some extent, was taken unawares. Everybody stood up and did their best. Nobody said: ‘No, this isn’t for me.’ But the sacrifice was huge: 540 UK healthcare workers dead.”

In many ways, Pimenta had been right to speak out, publicly, on all the occasions that he did. A study recently published in the Lancet found that Cummings’s trip eroded public trust in the lockdown and the government’s handling of the pandemic. Several reports have found that imposing an earlier lockdown in the UK, even by a week, as Pimenta suggested, would have saved thousands of lives. A recent Amnesty report found that the number of healthcare worker deaths in the UK during the pandemic is the highest per million in the world, a tragedy Pimenta believes was preventable. “If we’d had the capacity to cope,” he says, “all of that was so avoidable.” He blames the government: “A failure to prepare from the top down, a failure to build stocks, a failure to train and a failure to do it all on the hoof.”

Throughout the first wave, Pimenta watched as his colleagues were asked to risk their lives. “There were a lot of fractious moments when people were worried, and they were told not to worry, or that their worry was inducing other people to worry.” Since the outbreak of the pandemic, many people have asked: “Is it a doctor’s moral obligation to put his patients’ lives ahead of his own?” “You have to accept in your mind that it is a job, that it pays a wage, that you don’t have to stick it out,” Pimenta says. He thinks referring to healthcare workers as “heroes” can be problematic, because it suggests they have inhuman ability, that they are driven by some higher moral obligation or force, as if it is their duty to serve the rest of us, when really they are just normal people trying to get through the day.

Pimenta is “still processing” all that has happened to him. The past months have been “scarring” and “emotionally wearing”. He says he is unsure whether his decision to resign was worthwhile, that perhaps there might have been a different way, a more measured response. “Obviously, it didn’t make a tangible difference,” he says. “But on the other hand, opinions were changed. People understood that there was still an importance to the lockdown. Maybe it brought attention to that? So in many ways, yes, it was worth it. Was it worth it personally? Probably not.”

After he resigned, a friend asked Pimenta if he would be interested in getting into politics. It was a logical question – strangers on Twitter had asked the same – to which Pimenta replied, “Hell, no.” The pain inflicted on his family by negative reaction to his decision means he will engage in “public life no more than necessary”, he says. But he does have an interest in affecting policy, particularly within the NHS. His resignation catapulted him into “the national conversation”, he says, and he can see the seductive power in that, in being able to do more than “just shout at the TV” when he feels something is wrong. Maybe he’ll become a media doctor after all. “If I had 10 followers on Twitter, we wouldn’t be having this conversation,” he says. “But having access to that platform, and believing you have something to say that can change the national conversation… How could you not say something? Isn’t that duty?”

Duty of Care: One NHS Doctor’s Story of the Covid-19 Crisis by Dr Dominic Pimenta is published by Welbeck on 3 September at £8.99