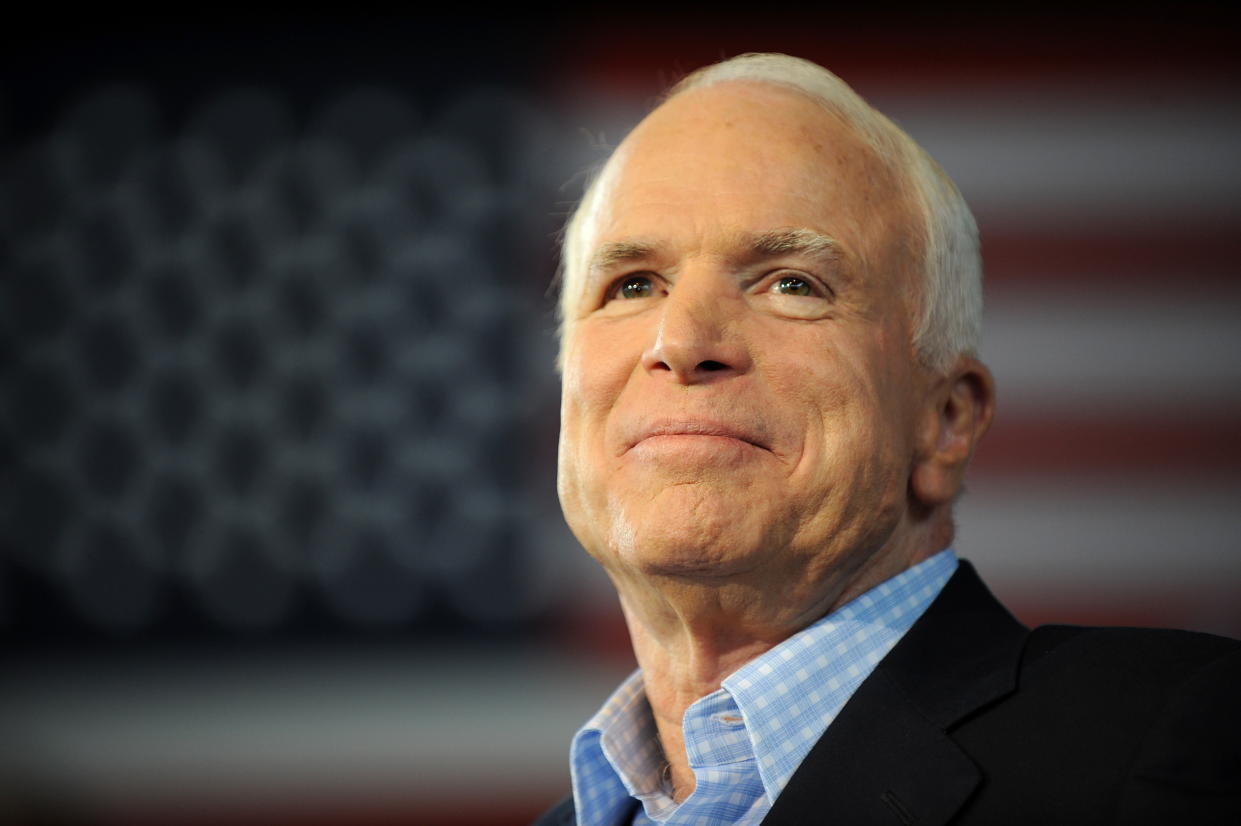

John McCain and the death of perspective

Donald Trump doesn’t remind you much of the brilliant actress Helen Mirren, but this week in Washington, with all the fuss over flags and funeral arrangements, he nicely reprised her Oscar-winning performance in “The Queen.” Maybe you’d call this version “The Drama Queen.”

If you didn’t see the 2006 film, the true-life premise goes like this: Princess Diana dies, and all of Britain loudly grieves. But Queen Elizabeth II, sitting in her palace, disdains her former daughter-in-law’s celebrity and prefers to handle the funeral privately, without making a big national to-do about it.

The new prime minister, Tony Blair (played by Michael Sheen, because there’s a law in England that Tony Blair can only be played by Michael Sheen), tries to help the aging Elizabeth see that times are changing, and that the monarchy itself could be in jeopardy. But the queen just can’t wrap her mind around the fact that the people love Diana in a way they can’t love her.

You see where I’m going with this?

In our version of “The Queen,” John McCain is the one whose death prompts a moment of national mourning, while the would-be monarch seethes at the implicit rejection. Except here the characters are essentially inverted.

Here it’s the character who represents decorum and duty whose death evokes a sense of abiding loss. And it’s the superficial celebrity type, the guy who trashes tradition and can’t get enough of the cameras, who finds himself isolated on the throne.

It’s almost enough — almost — to make you feel some sympathy for Trump, if you have any sense of pathos at all. Throughout his life, despite all the wealth and fame that came his way, all Trump ever wanted was some validation from the country’s cultured, moneyed establishment — people with class, to use the president’s vernacular.

It doesn’t take Jung to see that all of this raging against the machine, all these rallies meant to incite resentment and elicit deafening roars of adulation, are really just Trump’s way of handling rejection.

But even now, at the pinnacle of Trump’s unimaginable success, with all his money and generals and armored cars and all the rest, it’s the grizzled old warrior, a man for whom Trump harbored nothing but jealousy and contempt, whose death somehow unites the elite of both parties.

So intolerable is this for Trump, so stinging an indignity, that he was willing to hurriedly throw half of NAFTA back together and call it by another name just to give himself something to talk about.

Trump, like Queen Elizabeth, isn’t wrong to see some injustice in all of this. After all, he did what McCain never could, despite two gallant tries, which was to actually win the presidency.

And he’s right that we in the media have always slobbered over McCain (except for that brief period when he actually had the nomination in 2008), because he knew exactly how to make us feel vital and appreciated, whereas Trump could stop an asteroid from crashing into California by catching it with his bare hands, and all the editorial writers would want to know is why he didn’t deflect it toward Russia.

As the media critic Jack Shafer pointed out in a brave column this week, reporters who weren’t even born when McCain left a prison in North Vietnam reminisced about him this week as if they had shared his dorm at Annapolis.

I didn’t know McCain all that intimately, and especially not in later years. I spent a bunch of time with him during and after his 2000 presidential campaign, and interviewed him at length about foreign policy in 2008 for the New York Times Magazine. He didn’t appreciate the way the Times treated him that year, and my requests after that were mostly turned down.

I also had a hard time seeing McCain as an uncomplicated hero. While I respected his tenacity in passing his signature law, the reform of campaign finance in 2002, I came to believe over the years that McCain-Feingold, as it was known, did more harm than good to a functioning political system.

And choosing Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008 was easily the least patriotic thing McCain ever did. By cynically exploiting the extremism in his own party and further conflating celebrity with service, McCain cracked open the door through which Trump would eventually burst.

But all that said, I think I understand why the nation mourns McCain as we would a Roosevelt or an Eisenhower. It’s not because he was always right (he wasn’t), or because he was the last of the war heroes (he isn’t), or because he was such a warm-hearted and decent character (he could be, but he could also be petty and erratic).

It’s because he so embodied the one thing we miss most in our politics right now, which is a sense of perspective.

Most of the veterans in McCain’s generation had it, and since there was a time when every president and most senators had worn the uniform, the capital once had it, too.

When you’ve seen people die grisly deaths at a young age, when you’ve prayed fervently just to come home and find a spouse and a job and live out your years in decent health, you don’t look at the next election as a life-and-death situation. You don’t think of party loyalty as the truest test of human character in the universe.

We could call it existentialism, I guess, which is the word Norman Mailer once applied to John Kennedy. It’s the idea that you’re willing to take political risks for what’s right, because you know what genuine risk is all about.

So maybe your party leader or some blogger will get upset. You’ll still have your life and your limbs, and you can always find something to do with them other than voting yea or nay.

Trump, we understand, represents the death of perspective. He hasn’t a shred of it. Like anyone who equates survival with public success, all he can think about is what other people will think of him.

And this entire generation of political leaders isn’t a whole lot better. I’m not suggesting we’d be better off as a country if we manufactured more wars; we should be thankful that so few of today’s politicians had to endure the hell that most of their predecessors did going back to the nation’s birth.

But man, would it be nice to see a few more public servants speak and vote their consciences, even if it means they might draw a primary or lose a seat, because the worst that can happen is that they’ll have to change jobs, which is what most Americans do with regularity, and it doesn’t exempt them from having to show integrity.

That’s what McCain was — not all the time, but most of it. He was the guy who apologized to South Carolinians for sullying himself with the Confederate flag. He was the guy who told that woman at a town hall in Minnesota that Barack Obama was a patriot, not an Arab.

He was the guy who stood firm against torture as a tactic of war when the leaders of his own party found ways to justify it morally and legally, because not being able to raise your arms to comb your own hair in the morning has a way of clarifying what you mean by American values.

To quote a character from another great film, “This Is Spinal Tap,” that right there is “too much f***ing perspective.”

Maybe our politics can yet be reclaimed by a new generation of veterans who bring some of this same perspective to the cause. It’s no coincidence that Seth Moulton, once a young platoon leader on the battlefield in Iraq, is the Democratic congressman willing to tell his party’s chief boomer, Nancy Pelosi, that it’s time to get out of the way.

Mostly, though, we’re left with parties who behave like teams in thrall to the passions of their rowdiest fans, and a president whose understanding of human frailty begins and ends with a mirror.

So while the queen broods, her subjects mourn. We’re saying goodbye to a statesman, and we don’t have a lot of those left to lose.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: