Fighting the tyranny of ‘niceness’: why we need difficult women

Difficult. It’s a word that rests on a knife-edge: when applied to a woman, it can be admiring, fearful, insulting and dismissive, all at once. In 2016, it was used of Theresa May (she was “a bloody difficult woman,” Ken Clarke said, when she ran for Tory leader). A year later, it gave the US author Roxane Gay the title for her short story collection. The late Elizabeth Wurtzel took “in praise of difficult women” as the strapline for her feminist manifesto in 1998. The book’s main title was, simply, Bitch.

The word is particularly pointed since it recurs so often when women talk about the consequences of challenging sexism. The TV presenter Helen Skelton once described being groped on air by an interviewee while pregnant. She did not complain, she said, because “that’s just the culture that television breeds. No one wants to be difficult.” The actor Jennifer Lawrence told the Hollywood Reporter that she had once stood up to a rude director. The reaction to the incident left her worried that she would be punished by the industry. “Yeah,” chipped in fellow actor Emma Stone: “You were ‘difficult’.”

All this is edging towards the same idea, an idea that is imprinted on us from birth: that women are called unreasonable, selfish and unfeminine when they stand up for themselves. “I myself have never been able to find out precisely what feminism is,” wrote Rebecca West in 1913. “I only know that people call me a feminist whenever I express sentiments that differentiate me from a doormat, or a prostitute.”

So what does it mean to be a difficult woman? I’m not talking about being rude, thoughtless, obnoxious or a diva. First of all, difficult means complicated. A thumbs-up, thumbs-down approach to historical figures is boring and reductive. Most of us are more than one thing; no one is pure; everyone is “problematic”. Look back at early feminists and you will find women with views that are unpalatable to their modern sisters. You will find women with views that were unpalatable to their contemporaries. They were awkward and wrong-headed and obstinate and sometimes downright odd – and that helped them to defy the expectations placed on them. “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself,” wrote George Bernard Shaw in 1903. “Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” (Or, as I always catch myself adding, the unreasonable woman.) A history of feminism should not try to sand off the sharp corners of the movement’s pioneers – or write them out of the story entirely, if their sins are deemed too great. It must allow them to be just as flawed – just as human – as men. Women are people, and people are more interesting than cliches. We don’t have to be perfect to deserve equal rights.

In the name of inspiring little girls living in a male-dominated world, Rebel Girls doesn't so much airbrush Coco Chanel's story as sandblast it

The idea of role models is not necessarily a bad one, but the way they are used in feminism can dilute a radical political movement into feelgood inspiration porn. Holding up a few exceptions is no substitute for questioning the rules themselves, and in our rush to champion historical women, we are distorting the past. Take the wildly successful children’s book Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls, which has sold more than a million copies. It tells 100 “empowering, moving and inspirational” stories, promising that “these are true fairytales for heroines who definitely don’t need rescuing”. Its entry for the fashion designer Coco Chanel mentions that she wanted to start a business, and a “wealthy friend of hers lent her enough money to make her dream come true”. It does not mention that Chanel was the lover of a Nazi officer and very probably a spy for Hitler’s Germany. In the 1930s, she tried to remove that “wealthy friend” from the company under racist laws that forbade Jews to own businesses. In the name of inspiring little girls living in a male-dominated world, the book doesn’t so much airbrush Chanel’s story as sandblast it. Do you find her wartime collaboration with the Nazis “empowering”? I don’t, although admittedly she does sound like a woman who “didn’t need rescuing”. The real Coco Chanel was clever, prejudiced, talented, cynical – and interesting. The pale version of her boiled down to a feminist saint is not.

I can excuse that approach in a children’s book, but it’s alarming to see the same urge in adults. We cannot celebrate women’s history by stripping politics – and therefore conflict – from the narrative. Unfurl the bunting, and don’t ask too many questions! It creates a story of feminism where all the opponents are either cartoon baddies or mysteriously absent, where no hard compromises have to be made and internal disagreements are kicked under the carpet. The One True Way is obvious, and all Good People follow it. Feminists are on the right side of history, and we just have to wait for the world to catch up.

Life does not work like that. It would be much easier if feminist triumphs relied on defeating a few bogeymen, but grotesque sexists such as Donald Trump only have power because otherwise decent people voted for them. There were women who opposed female suffrage; women are the biggest consumers of magazines and websites that point out other women’s physical flaws; there is no gender gap among supporters of abortion rights. People are complicated, and making progress is complicated too. If modern feminism feels toothless, it is because it has retreated into two modes: empty celebration or shadow-boxing with outright bastards. Neither deals with difficulty, and so neither can make a difference.

Mothers struggled to understand why their daughters were desperate to have a big wedding and wear high heels

Women’s history should not be a shallow hunt for heroines. Too often, I see feminists castigating each other for admiring the Pankhursts (autocrats), Andrea Dworkin (too aggressive), Jane Austen (too middle-class), Margaret Atwood (worried about due process in claims of sexual harassment) and Germaine Greer (where do I start?). I recently read a piece about how I was “problematic” for having expressed sympathy for the supreme court nominee Brett Kavanaugh. My crime was to say that his confirmation hearings had been turned into a media circus – and that even those accused of sexual assault deserved better. The criticism reflects a desperate desire to pretend that thorny issues are straightforward. No more flawed humans struggling inside vast, complicated systems: there are good guys and bad guys, and it’s easy to tell them apart. We must restore the complexity to feminist pioneers. Their legacies might be contested, they might have made terrible strategic choices and they might have not have lived according to the ideals they preached. But they mattered. Their difficulty is part of the story.

Then there’s the second meaning of “difficult”. Any demand for greater rights faces opponents, and any advance creates a backlash. Changing the world is always difficult. At Dublin Castle in May 2018, waiting for the results of the Irish referendum on abortion law, I saw a banner that read: “If there is no struggle, there is no progress.” Those words come from a speech by Frederick Douglass, who campaigned for the end of the slave trade in the US. He wanted to make clear that “power concedes nothing without a demand”. In other words, campaigners have to be disruptive. They cannot take no for an answer. “Those who profess to favour freedom and yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without ploughing up the ground,” said Douglass. “They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.” Changing the world won’t make people like you. It will cause you pain. It will be difficult. It will feel like a struggle. You must accept the size of the mountain ahead of you, and start climbing it anyway.

Related: How #MeToo revealed the central rift within feminism today

Then there is the difficulty of womanhood itself. In a world built for men, women will always struggle to fit in. We are what Simone de Beauvoir called “the second sex”. Our bodies are different from the standard (male) human. Our sexual desires have traditionally been depicted as fluid, hard to read, unpredictable. Our life experiences are mysterious and unknowable; our minds are Freud’s “dark continent”. We are imagined to be on the wrong side of a world divided in two. Men are serious, women are silly. Men are rational, women are emotional. Men are strong, women are weak. Men are steadfast, women are fickle. Men are objective, women are subjective. Men are humanity, women are a subset of it. Men want sex and women grant or withhold it. Women are looked at; men do the looking. When we are victims, it is hard to believe us. “At the heart of the struggle of feminism to give rape, date rape, marital rape, domestic violence and workplace sexual harassment legal standing as crimes has been the necessity of making women credible and audible,” wrote Rebecca Solnit in Men Explain Things to Me. “Billions of women must be out there on this six-billion-person planet being told that they are not reliable witnesses to their own lives, that the truth is not their property, now or ever.”

¶

My favourite definition of feminism comes from the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. A feminist, she said, is someone who believes in “the social, economic and political equality of the sexes”. That sounds straightforward, but feminism is endlessly difficult. The last 10 years have been praised for “changing the culture”, but led only to a few concrete victories. The #MeToo movement turned into a conversation about borderline cases and has not led to any substantial legal reforms. Abortion rights came under threat in eastern Europe and the southern United States. Gang-rape cases convulsed India and Spain. Free universal childcare was as much a dream as it had been in the 1970s. And the backlash has been brutal. Across the world, from Vladimir Putin in Russia to Narendra Modi in India to Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, populists and nationalists are pushing a return to traditional gender roles, while the US president boasted of grabbing women “by the pussy”.

Today’s feminist movement might be louder than previous generations, but is also more fractured, making it harder to achieve progress on any individual issue. “Cancel culture” ensures that any feminist icon’s reputation feels fragile and provisional. We barely anoint a new heroine before we tear her down again. “Sisterhood is powerful,” the activist Ti-Grace Atkinson once said. “It kills. Mostly sisters.” Feminism often feels mired in petty arguments, with younger women casually denigrating the achievements of their predecessors. “Cancel the second wave,” read one headline. When I talked at an event about the fights for equal pay and domestic-violence shelters, one twentysomething woman casually replied: “Yeah, but all that stuff is sorted.”

Feminism will always be difficult because it tries to represent half of humanity: 3.5 billion people (and counting) drawn from every race, class, country and religion. It is revolutionary, challenging the most fundamental structures of our society. It is deeply personal, illuminating our most intimate experiences and personal relationships. It rejects the division between the public and private spheres. It gets everywhere, from boardrooms to bedrooms. It leaves no part of our lives untouched. It is both theory and practice.

And there is another problem, unique to feminism. It is a movement run by women, for women. And what do we expect from women? Perfection. Selflessness. Care. Girls are instructed to be “ladylike” to keep them quiet and docile. Motherhood is championed as a journey of endless self-sacrifice. Random men tell us to “cheer up” in the street, because God forbid our own emotions should impinge on anyone else’s day. If we raise our voices, we are “shrill”. Our ambition is suspicious. Our anger is portrayed as unnatural, horrifying, disfiguring: who needs to listen to the “nag”, the “hysteric” or the “angry black woman”?

All this is extremely unhelpful if you want to go out and cause trouble – the kind of trouble that leads to legal and cultural change. We pick apart feminism to see its failings, as if to reassure ourselves that women aren’t getting above their station. We describe women who challenge authority or seek power as unladylike, talkative, insistent, self-obsessed. We accuse them of “putting themselves forward”. The critic Emily Nussbaum nailed the problem: “When you’re put on a pedestal, the whole world gets to upskirt you.”

For that reason, feminism has a particular duty to fight “the tyranny of niceness” – which is, and has always been, one of the most potent forces holding women back. Feminism is not a self-help movement, dedicated to making everyone feel better about their lives. It is a radical demand to overturn the status quo. It sometimes has to cause upset. “I cannot personally think of any widespread injustice that has been remedied by plodding worthily down the middle of the road, smiling and smiling,” wrote Jill Tweedie in 1971. “If you are sure of the justice of your cause it must be better to have people thinking of it with initial anger than not thinking at all.”

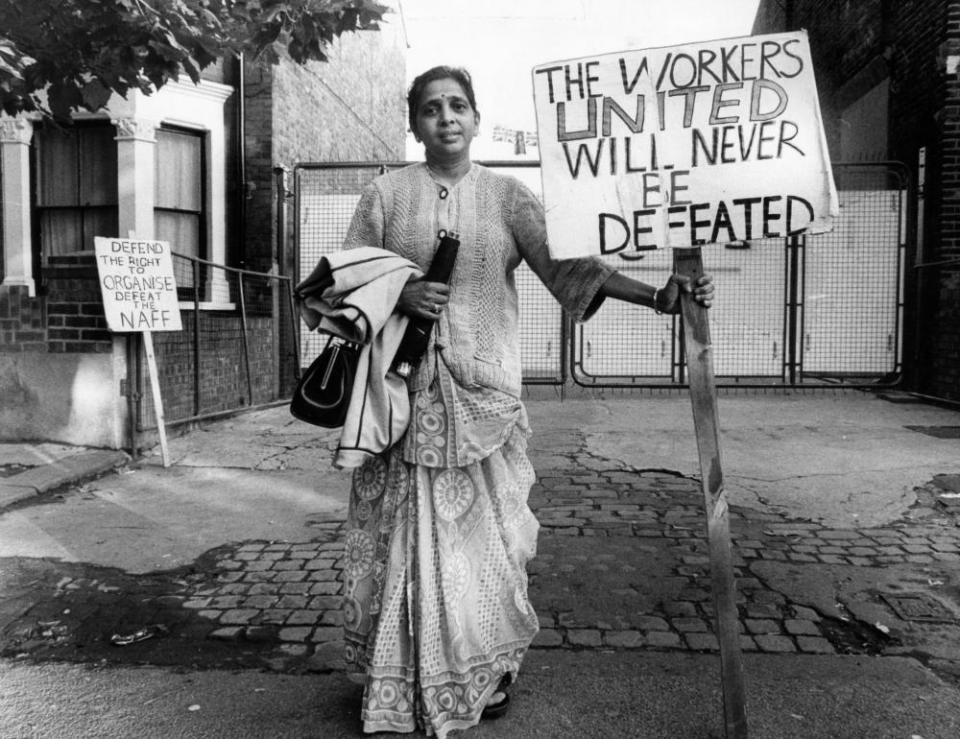

In the early 20th century, the contraception pioneer Marie Stopes showed thousands of women how to enjoy sex – and how to stop risking their lives through endless pregnancies. She was also a domineering, self-mythologising eugenicist. The suffragettes helped to secure the vote for women, but the cost was bombings, arson, criminal damage and, in one case, throwing a hatchet at the prime minister. Today, we would call them terrorists. Jayaben Desai – who led the strikes at Grunwick in the 1970s, and showed Britain that “working class” was not synonymous with white and male – ultimately failed, and her protest contributed to the Thatcherite backlash against trade unions. The woman who founded the first domestic violence refuge in Britain, Erin Pizzey, is now a men’s rights activist who says feminism is destroying the family. Selma James preached the gospel of universal basic income: only she called it “wages for housework” and wanted it to go to women, so she was ignored. Caroline Norton, who fought so hard to reform Britain’s child custody laws, relied on her own middle-class respectability to make her arguments.

All of these women belong in the history of feminism, not in spite of their flaws, but because we are all flawed. We have to resist the modern impulse to pick one of two settings: airbrush or discard.

¶

In the past decade, the internet – and particularly social media – has prompted a flowering of feminist activism. The Everyday Sexism project website, #MeToo and the Caitlin Moran-inspired publishing boom awakened a new generation to the idea that, no, sexism hadn’t been solved by their mothers and grandmothers. Their anger, their creativity and the power of their voices renewed feminism, creating its fourth wave.

Underneath all the energy, though, a split could be observed. Some young activists saw the older generation as conservatives, wedded to fixed ideas of what men and women could be, whereas they felt gender was much more fluid and playful. Their mothers were equally bemused. They had tried to smash beauty standards and restrictive ideas about the nuclear family. They struggled to understand why their daughters were so desperate to have a big wedding, wear high heels, pore over Facetuned selfies. Feminism can, and must, contain all these contradictions, the differing priorities of difficult women. But one thing should unite us: we should still try to turn our outrage into political power. The fourth wave was beautifully noisy and attention-grabbing, but now we need concrete victories that will last in a way hashtag campaigns cannot. The #MeToo movement is a dead end without structural change, such as ensuring full and free access to employment tribunals.

The fifth wave, if there is to be one, should look again at the seven demands of the first Women’s Liberation Movement conference, in Oxford 50 years ago this month. Equal pay. Equal educational and job opportunities. Free contraception and abortion on demand. Free 24-hour childcare. Legal and financial independence for all women. The right to a self-defined sexuality. Freedom from intimidation and violence. These are a reminder of how long the struggle has been – Northern Ireland only gained abortion rights last year – and how much there is left to do. Women are legally entitled to be paid the same as men, but as Samira Ahmed’s case against the BBC showed, laws are worthless if they are not enforced. Single parents (who are overwhelmingly female) still face a high risk of poverty. Lesbians are still attacked for saying “no” to the Great Almighty Penis. Social media and smartphones have created new expressions of misogyny, such as “revenge porn”, which rely on the same old mechanisms of intimidation and shame.

You might notice that I haven’t said much about some of the hardy perennials of feminist commentary: leg-shaving, bra-burning, pube-waxing. It’s not because I don’t care about them or haven’t thought about them. I don’t wear high heels (can’t walk in them, and object to the principle of a shoe that makes your feet less comfortable). I didn’t take my husband’s surname. I don’t watch pornography. I’m 100% pro‑bra as I have a cup size that requires serious cantilevering. I shave my legs because my socialised disgust with female body hair runs so deep that I couldn’t concentrate on anything else if I had furry calves. But all of these are ultimately personal decisions, rather than collective actions. And since we live in a deeply individualist society, debates over women’s choices on these topics will never struggle to get airtime. My most hated headline format – “Can you be a feminist and … ” – will never, ever die. In this climate, the most radical thing we can do is resist treating everything as a personal choice, and resist turning feminism into a referendum on those choices. Let’s swim against the tide by talking instead about what we can do together.

Change requires us to put aside our egos, and our differences, and focus on our shared goals. The suffragettes saw themselves as an army. Jayaben Desai did not go on strike alone. Erin Pizzey and her “battered wives” made sure the government could not ignore them, by staging a sit-in at Downing Street. Feminism will never be free of infighting, of personality clashes and contests over priorities. It will never be perfect, or nice. But no wonder sexists and reactionaries are scared of it, because – by God, can it get things done •