Here Is How Biden Can Attack High Drug Prices Without Congress

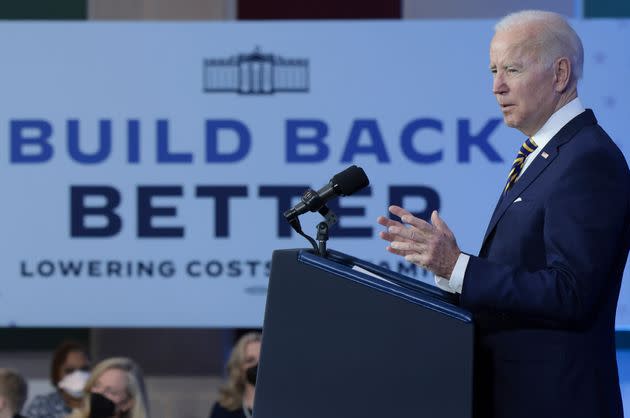

Lowering the price of prescription drugs is a longtime goal for Democrats, and for most of last year it looked like President Joe Biden and his allies were on track to do just that, thanks to an initiative in their “Build Back Better” legislation. But Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) is blocking that bill and it’s an open question whether Democrats can still pass some version of it.

Biden has some other options on drug prices, however, and one involves an especially expensive cancer drug called Xtandi. UCLA researchers first developed it nearly two decades ago, with the help of federal research funds, and today it is helping extend the lives of prostate cancer patients all over the world.

But here in the U.S., the manufacturer that has exclusive rights to produce Xtandi charges dramatically more than what it charges in some other developed countries. As a result, treating an American patient for one full year costs almost $190,000, based on publicly listed wholesale prices. The federal government covers the bulk of that, mostly through Medicare, which spent more than $5 billion on Xtandi between 2015 and 2019. Private insurers also pick up a share, as do individuals taking the drug. Their out-of-pocket costs can reach $10,000.

Late last year, some prostate cancer patients asked the Biden administration to intervene ― by invoking executive authority under existing laws so that other manufacturers could produce cheaper, generic versions. The request has gotten support from progressive heavyweights Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and activist Ady Barkan, organizations including Social Security Works and Public Citizen, as well as two influential liberal columnists: David Dayen of The American Prospect and Michael Hiltzik of the Los Angeles Times.

One reason for the attention is that this isn’t just about the price of a single cancer treatment. The Biden administration and its successors could use the same authority on other high-priced pharmaceuticals. “This isn’t the end-all, be-all,” says James Love, the director of Knowledge Ecology International who has been leading the campaign to intervene on Xtandi. “But it will set a precedent, with implications way beyond this one drug.”

The cause is not new. A variety of activists, legal experts and consumer advocates have been begging the federal government to use this same executive authority for years. Neither the Obama nor the Trump administration would. The question now is whether the Biden administration will prove more receptive.

The answer, which could come this week, will depend on how the administration chooses to interpret its authority under existing patent laws ― and where it lands on the perennial debate over whether regulating drug prices will deter medical innovation.

The answer may also provide a clue on how Biden plans to govern for the rest of his term. If Republicans get control of Congress in the midterms, passing ambitious legislation will be almost impossible, making executive action the best and maybe only way to pursue his domestic agenda. The Xtandi decision could be an early test of how aggressively he’s willing to deploy it.

The President Has Two Sources Of Authority

The idea of the federal government effectively breaching a company’s patent protection may sound radical. It’s not.

Under existing laws ― specifically, Section 1498(a) of the U.S. Code covering the judiciary ― the federal government has the power to license production of any patented good to another company, or to manufacture that good on its own, just so long as it is for government use. Companies holding patents can seek “reasonable and complete” compensation from the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, but they can’t stop the government from acting.

Section 1498(a) dates back to the early 20th century and functions a lot like eminent domain, allowing the federal government to acquire patented goods for a public purpose ― and then paying the owner of the patent in return. The Defense Department has used this power in order to guarantee production of essential parts for the U.S. military arsenal, or to prevent manufacturers holding the patents from demanding outrageous prices.

The federal government has not taken advantage of 1498(a) for medical goods in modern history. But it did threaten to do so in one very famous instance ― after 9/11, amid fears that terrorists would unleash some kind of bioweapon on the public. The Bush administration wanted to stockpile the antibiotic Cipro, which the manufacturer Bayer sold exclusively at a high price. The administration threatened to use its 1498(a) authority and license production of a generic version of Cipro if Bayer didn’t agree to provide mass doses of the drug at lower prices. Bayer agreed.

This isn’t the end-all, be-all. But it will set a precedent, with implications way beyond this one drug.James Love, director of Knowledge Ecology International

Progressives and their allies think the Cipro case shouldn’t be exceptional. They want the federal government to threaten use of 1498(a) for other high-priced drugs, starting with Xtandi, prompting manufacturers to lower their prices as Bayer did with Cipro ― or, failing that, allowing production of cheap generics by other firms.

The 1498(a) power is not the only potential tool for lowering drug prices through executive power. There are also the provisions of the Bayh-Dole Act, 1980 legislation named for the two former U.S. senators who sponsored it, Kansas Republican Robert Dole and Indiana Democrat Birch Bayh.

Bayh-Dole gave private entities the right to patent and sell drugs developed with the help of federal research funding, in the hopes of providing more incentive for private industry to turn research breakthroughs into usable medicines. By most accounts, it has done just that, contributing to the creation of countless medical breakthroughs for which the drug industry has in turn reaped massive profits.

But Bayh-Dole also seeks to make sure the public is getting a fair return on its investment. It does so through two separate legal mechanisms, one of which is known as “march-in rights,” which give the government the right to produce a drug on its own or to license production to other companies when a manufacturer has not made a product available to the public on a “reasonable basis.”

There Are Two Big Arguments Against Using The Authority

Prior to last year, patients and companies had asked the federal government to use Bayh-Dole to lower the price of a drug six times. The petitions have always gone to the National Institutes of Health, because of its role in administering federal research money, and NIH has always said no.

The most recent instance was in 2016, the first time prostate cancer patients petitioned for action on Xtandi. NIH’s argument was that Bayh-Dole was not designed to give the federal government power to threaten patents simply for the sake of lowering a drug’s price. That is also the view of the Bayh-Dole Coalition, an interest group whose members include pharmaceutical companies plus universities that sometimes reap big windfalls from the drugs their researchers help develop.

“While making health care more affordable is a laudable goal, it can’t be done on the back of Bayh-Dole,” Joseph Allen, the coalition’s director and a former adviser to Bayh, wrote in a Stat News column last fall. “That’s not how the law works.”

As proof, the coalition and its allies like to cite a 2002 letter to the editor of The Washington Post that Bayh and Dole co-signed, when the possibility of using the law to lower drug prices first got serious attention. “The law makes no reference to a reasonable price that should be dictated by the government,” Bayh and Dole wrote. “This omission was intentional.”

But there’s reason to wonder how faithfully Bayh and Dole were recounting the bill’s history. By 2002, the two had retired from Congress and were in the lobbying business, at firms representing pharmaceutical interests. Two decades before, when Bayh and Dole were writing and defending their legislation from critics, they had offered repeated assurances that it would protect the public from profiteering ― precisely because critics were worried about that.

While making health care more affordable is a laudable goal, it can’t be done on the back of Bayh-Dole. That’s not how the law works.Joseph Allen, director of the Bayh-Dole Coalition

“There are countless references in the legislative record to the need to maintain competitive market conditions through the exercise of march-in rights,” legal scholars Peter Arno and Michael Davis wrote in a seminal 2002 law review article laying out the case for using Bayh-Dole to reduce drug prices.

The other case against unleashing executive authority on drug prices is that it would threaten innovation. As this argument goes, the profits from expensive drugs like Xtandi offset losses for all experimental treatments that never make it to approval, attracting the investment capital that underwrites research and development. Reduce prices and profits with Bayh-Dole or 1498(a) authority, and there will be fewer breakthroughs, according to this line of thinking.

The counterargument is that the profits from drugs like Xandi go far beyond what it takes to attract capital, especially when so much of what passes for drug company innovation today doesn’t really add value. And if the goal is to support innovation, progressives and their allies say, there are more efficient ways to do that ― like having the federal government make cheap capital available to smaller firms that are the ones doing most of the development work these days.

This debate should sound familiar, because it’s exactly the same debate that comes up with every attempt to exert some kind of government control over drug prices, including the ongoing arguments about the price regulation proposals in Build Back Better. But when it comes specifically to the use of 1498(a) and Bayh-Dole, the risk to future innovation would seem to be small, simply because of the practical limits on just how much either can achieve.

Every request to intervene in the price of a drug would take time for the federal government to process, and many would prompt lengthy court battles. And while using 1498(a) or Bayh-Dole even a handful of times could have a powerful signaling effect, causing drugmakers to think twice when they try to jack up prices, ultimately it would have a fraction of the impact that strong legislation would.

But strong legislation isn’t on the agenda right now. The most optimistic scenario for Democrats is to rescue and pass Build Back Better’s drug price provisions, which they have already scaled back dramatically in order to appease a handful of skeptical lawmakers with close ties to the drug industry, including Rep. Scott Peters (D-Calif.) and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.). In that context, making the most of executive authority may be the most far-reaching opportunity Biden has to make progress on pharmaceutical prices.

This Is A Test Of How Aggressively Biden Will Govern

Whether he will use this particular opportunity is another matter. Biden has his own close ties to the pharmaceutical industry through his lengthy involvement with cancer research and is likely to take their arguments seriously.

Biden may also be reluctant to challenge officials at NIH who have long opposed expansive readings of Bayh-Dole and 1498(a) ― whether because they think it will deter innovation, because they believe they may someday profit from their own work with industry, or both. Biden may be especially deferential to NIH now that he has tapped its former director, the famed scientist Francis Collins, to serve (temporarily) as his top science adviser. It was Collins who presided over the recent petition rejections when he was in charge of NIH.

But in July, Biden put a hold on a regulatory proposal from the Trump administration that would have forbid the use of Bayh-Dole to control prices. Two months later, Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra issued a report on drug pricing that referenced march-in rights specifically. Advocates on both sides of the debate interpreted these developments as a signal that Biden is open to the idea.

And the politics would certainly seem to favor action. If the prescription drug reforms of Build Back Better don’t become law (and maybe even if they do) Biden will be eager to demonstrate progress on drug prices, especially given all of the polling showing that efforts to lower drug prices are wildly popular.

Whatever happens with Xtandi and drugs, this probably won’t be the last time Biden faces a choice like this. If he is facing a Republican House, a Republican Senate, or both starting in 2023, the only way forward on everything from climate change to labor standards will be through the ambitious and sometimes creative use of executive power.

These efforts will inevitably face resistance, from outside his administration and sometimes within it. If he can’t overcome that resistance, he’s not going to get much done.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.