Brazil austerity fervour threatens fight against coronavirus

By Jamie McGeever

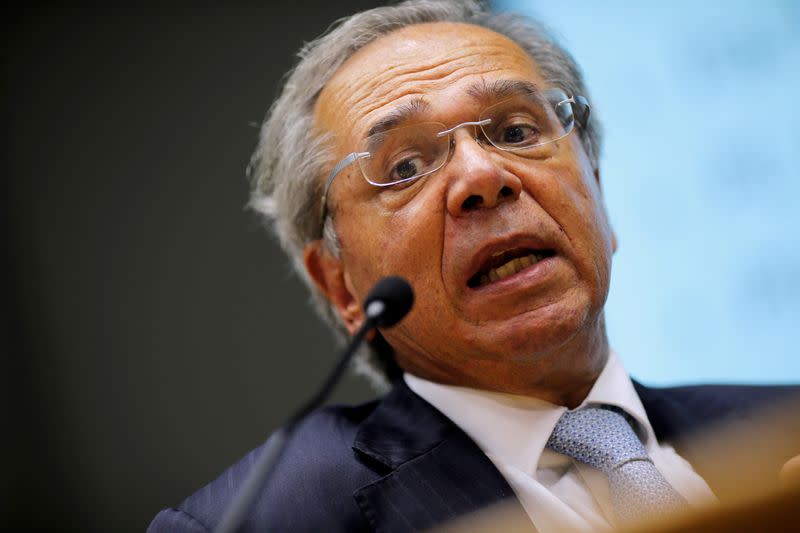

BRASILIA (Reuters) - The fiscal reforms championed by Brazilian Economy Minister Paulo Guedes may be dead, but the austerity-bound thinking behind them is alive and well, and could tie Brazil's hands in tackling its looming economic and public health crises.

While countries around the world rip up their budget rules and throw trillions of dollars at mitigating the damage from the coronavirus pandemic, some observers say Brazil's emergency spending plans are far too cautious and limited.

The reason for that is largely political. President Jair Bolsonaro, who took office in January 2019 promising an economic turnaround, has repeatedly blamed media "hysteria" for causing panic around what he dubs "a little flu." He has called the virtual shutdown of commerce across many states a "crime."

Bolsonaro's scepticism surrounding coronavirus is matched by the Economy Ministry's reluctance to cool its ardour for austerity and do whatever it takes, in fiscal terms, to limit the economic damage.

"Guedes and his team seem totally detached from the economic consensus on what needs to be done to fight this impending crisis," said Julia Braga, associate professor of economics at the Universidade Federal Fluminense in Rio de Janeiro state.

The government has proposed fiscal measures worth around 180 billion reais ($36 billion), or 2.24% of gross domestic product, according to JP Morgan, while Goldman Sachs reckons the "multi-pronged package of fiscal and quasi-fiscal support measures" is worth more than 3.0% of GDP.

They include tax breaks for households and companies, corporate tax deferrals, bringing forward social assistance payments, and making it easier to access workers' severance funds.

Many developed countries have taken much bolder fiscal steps, pumping hundreds of billions of dollars directly into households, guaranteeing up to 80% of workers' wages, and ramping up spending on health and other services.

Guedes said this weekend that overall, the measures add up to as much as 5% of GDP. But that includes some actions taken by the central bank, and what's more, only a small part of the government proposals comprises new spending.

Calls for Brazil to loosen its purse strings are growing louder by the day.

"Their reforms are based on fiscal austerity, and this agenda is absolutely incompatible with the situation the country finds itself in," said Marcelo Ramos, federal lawmaker from the centre-right Liberal Party.

"There is no point in saving the economy if we don't have a country any more. It's time to save people," he said.

Economists at Citi estimate that, in general, governments need to take fiscal measures worth at least 5% of GDP to compensate the drag on growth, calm financial markets and avert a sluggish recovery and rising inequality.

STILL NO 'WAR BUDGET'

The Economy Ministry's plans this year for major tax reform, privatisations, trimming the public-sector payroll and revamping the framework for state and federal finances have been dealt a fatal blow by coronavirus and the likely economic downturn.

Ministry officials have said repeatedly in recent weeks that despite the magnitude of the crisis, Brazil cannot afford to put its long-term fiscal targets at risk.

They insist any crisis-fighting spending will only apply to this year and be done in stages. They use words like "caution" and "prudence" in relation to spending, while reaffirming their zeal for reducing the public deficit.

Economic Policy Secretary Adolfo Sachsida also said in early March that the best vaccine against coronavirus would be to "press ahead with economic reforms," putting Brazil on sounder footing for a strong recovery.

Officials admit the government will miss its 2020 primary budget deficit goal of 124 billion reais. The projected shortfall is now over 350 billion reais as tax, oil and privatisation revenues slump while spending is likely to rise.

But they insist that a constitutional budget cap is sacrosanct, limiting government spending growth in each year to the previous year's annual inflation rate.

With 90% of the federal budget devoted to non-discretionary spending such as social security, education and public sector salaries, room for manoeuvre is virtually non-existent.

To get around this, Rodrigo Maia, speaker of the lower house of Congress, proposed that Brazil spend between 300 billion and 400 billion reais in emergency funds, creating a "war budget" under which ordinary fiscal rules do not apply. He floated the idea on March 22, but a bill has yet to be submitted.

"They seem very reluctant to take the big steps necessary, and are only doing so under pressure. But there is no doubt they will have to do more," said UFF's Braga. "This will be much worse than 2008-09."

(Reporting by Jamie McGeever; Editing by Christian Plumb and Grant McCool)