Broadway shows this year strike a relevant chord

NEW YORK (AP) — A man works for decades and can barely scrape together enough pennies to fix his fridge. He shuffles into his home late after fruitless workdays, filled with an increasingly urgent despair. Then to top it all off, he's fired.

"Oh boy, oh boy," he mutters quietly to himself at his empty table.

It could be a scene set today, but it's 1949 and it's Arthur Miller's play, "Death of a Salesman."

A Tony Award-nominated revival of the drama currently on Broadway is one of many shows this season that mirror today's tougher times — not only economically, but in a subtle way, socially and politically.

Willy Loman is a man destroyed by his own stubborn belief in the glory of American capitalism and its spell of success. The show works in current day on a micro level; Loman the salesman could be any a middle-class man crushed under the recession. But it also could be a macro-level symbol of the smoke-and-mirrors sham of sub-prime mortgages. When Willy's dream world collapses, so does his life — not unlike our economy.

It was something Miller, who wrote the play at 33, never expected.

"I couldn't have predicted that a work like 'Death of a Salesman' would take on the proportions it has," Miller said in an interview in 1988. He died in 2005. "Originally, it was a literal play about a literal salesman, but it has become a bit of a myth, not only here but in many other parts of the world."

Mike Nichols, director of the revival that critics have hailed as devastating, said the play remains relevant while other shows recede because it's about two universal themes: The economy, yes, but also fathers and sons.

"Some great plays are left sort of where they happened, because the world changes, and then they can be great plays, like 'The Importance of Being Earnest,' but the society has changed," Nichols said in a recent interview. "You can't say that's what things are like now. But you can with this — it remains frighteningly apt."

The play at the Barrymore Theatre stars Philip Seymour Hoffman as the doleful Willy Loman and we watch, transfixed, as he descends, beaten by his own mind as well as by life, until the inevitable bottom. "My God, Willy Loman is my father," one audience member whispered to another during a recent performance. "And Biff is mine," the other replied, referring to Loman's eldest son, the source of Willy's pride, delusion and his greatest disappointment.

The production hews close to the original that starred Lee J. Cobb and was directed by Elia Kazan. The set is a recreation of the original design, a skeleton of with wood and steel giving way to abstract girders and silhouettes of trees.

Nichols, who directed the film "The Graduate" and the play "Barefoot in the Park," said he wanted to stage the show in part because he felt Hoffman was meant to play the lead role and it was right for this period we're in.

"It seemed apt for the moment for now, for the time," he said.

The idea of selling to Nichols seemed more relevant today than ever. Drug companies sell on television, televisions are sold on the Internet. And everyone is selling himself — and can pretend to be whoever he wants to be, Nichols said.

"It's so startling once you're in the middle of it," Nichols said. "It's everyone. Everyone is a salesman, and they're selling themselves, online. Everyone is on Facebook. You can't get into certain places online without Facebook. That's only about being known."

Other Broadway works that became strangely prescient include the revival of Gore Vidal's "The Best Man," which rang true this election cycle with its debate between elitism and populism despite being 50 years old, and David Henry Hwang's "Chinglish," which has uncanny echoes to the political scandal surrounding former Chinese Politburo member Bo Xilai. There's also the battle over gentrification in Bruce Norris' "Clybourne Park."

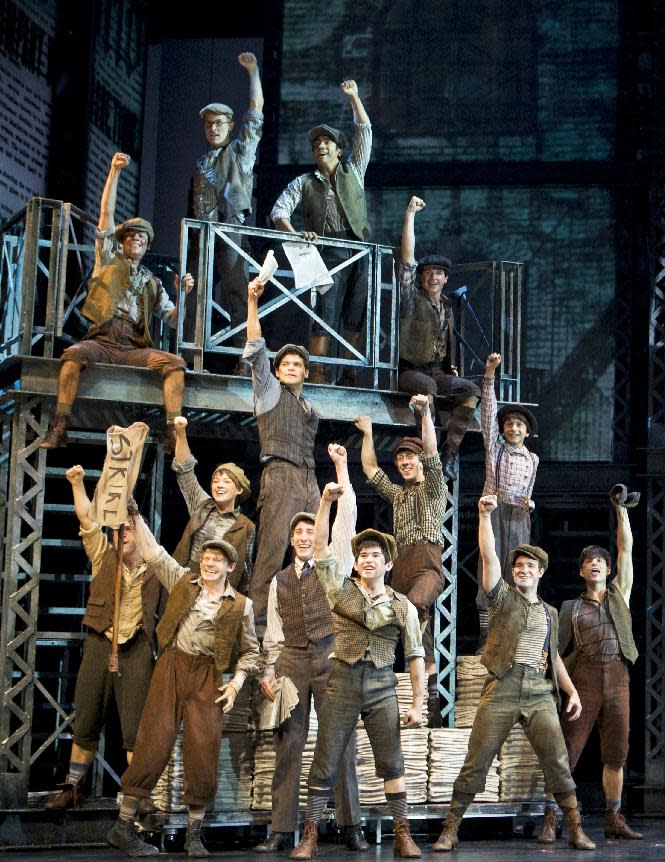

And "Newsies," which earned eight Tony nominations, is a not-so-subtle love letter to unions wrapped in Disney tinsel as a turn-of-the-century song-and-dance show starring lithe boys in knickers doing back flips. The musical, and its precursor film, is based on newsboy strike of 1899.

Circulation at the turn of the century depended on a cadre of boys hawking newspapers — or, as they were known, papes — around the city. (Extra, extra, read all about it!) They bought papers, sold them at a small profit and had to keep the ones they couldn't sell. When Joseph Pulitzer raised the price of his paper, "The World," the boys formed a union and went on strike, and after two weeks of rallies and rabble rousing, they compromised. Publishers would continue to charge a higher price, but they agreed to buy back any papers the newsies couldn't sell.

"All kids are seeing now is 'unions are evil,' 'America can't be great, because we have unions.' What kind of horrible message is that?" asked Harvey Fierstein, playwright and actor, who wrote the book, based on the Disney film by Bob Tzudiker and Noni White. "It's a message delivered by certain politicians."

Fierstein said the title was the most requested by high school producers of all in the Disney cannon, but it had never been turned into an official staged show. So Fierstein, working with Alan Menken who wrote the songs for the film too, wrote a story that would portray unions in a positive light, as a way to sneak in a lesson to the masses.

"An America without equal ground is not America," he said. "So I saw that struggle and fight in 'Newsies.' I knew it was going to reach that younger audience, and so I wanted to teach them something, and to give girls a good role model."

The role model he's speaking of is the character of Katherine, the cub reporter covering the strike and publicizing it as a "children's crusade." Despite the subject matter, the play is by no means heavy — there are tap dances and shuffles and high kicks, and upbeat numbers like "King of New York," that kept a recent audience full of young girls in squealing delight.

The idea of a ragtag youthful proletariat uprising smacks of last fall's Occupy Wall Street movement — but Fierstein said the show for him is more in the spirit of the 1960s hippies than the 99 percenters.

"The show is definitely about stuff that everyone except for the 1 percent has to worry about," he said. "But I'd really compare to the 1960s. I just want to say, in an innocent kind of Disney, way: Don't give it away kids, this is your world."

___

Online:

http://www.deathofasalesmanbroadway.com

http://newsiesthemusical.com