Cancer-killing virus could deliver instructions that unmask tumours and prevent disease returning, study finds

Scientists using viruses to combat cancer have found a way to prevent the disease from returning by targetting the healthy cells tumours enslave to use as camouflage and life support.

University of Oxford researchers say this is the first time they have been able to target the fibroblasts cells which have been “tricked” into supporting the tumours without causing toxic reactions in healthy tissue.

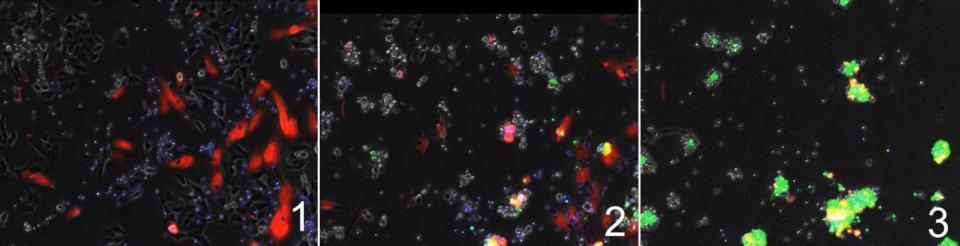

This two-pronged attack could allow doctors to directly target tumours and unmask the cancer cells, which “kick starts” the immune system causing it to attack the deadly invader.

While it still needs to be proven in human trials, it was safe and effective in tests on mice and in-lab samples of human carcinomas – the most common group of tumours that arise in the lining of the major organs or skin.

“Even when most of the cancer cells in a carcinoma are killed, fibroblasts can protect the residual cancer cells and help them to recover and flourish,” said Dr Kerry Fisher, from the University of Oxford’s Department of Oncology, who led the research.

“Until now, there has not been any way to kill both cancer cells and the fibroblasts protecting them at the same time, without harming the rest of the body.”

While the technique is new, the virus which attacks the carcinoma is already part of human trials to test their safety and effectiveness as an immunotherapy treatment. This is a broad term for a new generation of techniques which use the immune system as part of the treatment, in this case the virus kills cancer cells and this damage also triggers the immune reaction.

“We hope our modified virus will be moving towards clinical trials as early as next year to find out if it is safe and effective in people with cancer,” Dr Fisher added.

The findings, published in the journal Cancer Research on Sunday used a virus called enadenotucirev which has been developed to only target cancer cells and leave healthy ones untouched.

Once inside a cell, viruses replicate and burst out, rupturing their host and spreading to other cancer cells.

However, Dr Fisher and colleagues made use of another property of viruses which allows them to insert genes into infected host cells’ DNA. In this case, the recipe to wipe out enslaved fibroblasts.

Fibroblasts are one of the key cell types in the body that build up connective tissues like collagen, repair wounds and maintain the environment outside of the body’s cells.

An untargeted attack on them could destroy them throughout the body, and cause serious side effects by disrupting these functions, so a cancer-targetting virus is the perfect delivery system.

The genetic instructions inserted into the cancer cell force it to produce a protein molecule called, bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE), and this acts like a glue to bind fibroblasts with a key immune system unit called a T-cell.

Also known as killer cells, T-cells are the search and destroy units of the immune system. They spot defective cells and destroy them and once tumours started to produce BiTT and glue them to fibroblasts, it also alerts the immune system to the wider tumour.

“We hijacked the virus’s machinery so the T-cell engager would be made only in infected cancer cells and nowhere else in the body,” said Dr Joshua Freedman another author of the study from Oxford University said. “The T-cell engager molecule is so powerful that it can activate immune cells inside the tumour, which are being suppressed by the cancer, to attack the fibroblasts.”

Dr Michelle Lockley, from Cancer Research UK, who was not part of the study, said: “This work in human tumour samples is encouraging, but can be complicated – one of the biggest challenges of immunotherapies is predicting how well they will work with the patient’s immune system, and understanding what the side effects could be.”