China protests use health threats as rallying cry

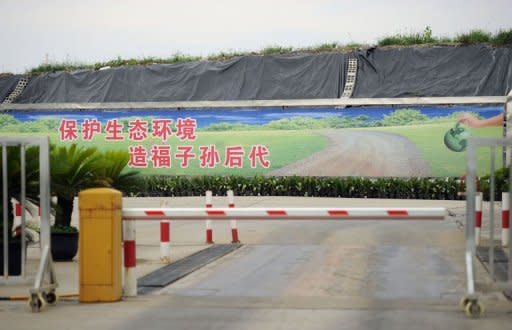

When the wind blows in one Shanghai suburb, residents can smell the stench rising from a towering garbage dump, feared to be so harmful it can make people vomit and cause birth defects. Now residents of Songjiang district are raising a stink about the future of the landfill, one of a series of recent protests across China as people hold the government more accountable for health and environmental problems. "All the garbage in Songjiang comes here," said Chen Chunhui, who grew up nearby. "This is a residential district, so people are making a fuss. They say if you smell it, your baby will be a freak." Hundreds took to the streets in late May and dozens again in early June to oppose the landfill and a planned garbage incinerator, which officials had proposed to solve the festering problem. The May protest is believed to be Shanghai's largest since 2008, when hundreds marched against an extension of the city's high-speed "maglev" train line, prompting the government to suspend the project indefinitely. The Songjiang protesters -- who are largely young, educated and not necessarily Shanghai natives -- claim the incinerator would spew dangerous toxins and slammed the local government's lack of transparency on the project. "Oppose the incinerator, protect our homes," said one protester wearing a surgical mask to show the potential harm at the June demonstration, which took place under the watchful eyes of nearly 100 police. Government officials announced in May that Songjiang would build the 250-million-yuan ($40-million) incinerator on its current landfill site as the population swells. But residents claim the incinerator could affect the health of hundreds of thousands of people and call for moving the landfill, which towers up to 17 metres (19 yards) and covers an area the size of a football field. Environmental pollution and perceived health threats are sparking protests elsewhere in China, helped by social media which allows organisers to publicise their causes and rally others despite tight control in the one-party state. Last year, thousands of protestors halted production at a polluting solar panel factory in the eastern city of Haining, while residents of the northeastern city of Dalian stopped a planned petrochemical plant. Earlier this month in the southwestern province of Sichuan, hundreds of protestors clashed with police over a planned metals plant in Shifang city and forced the project to be scrapped. "This nascent urban middle class is increasingly unwilling to accept perceived threats to their quality of life, so you are having a greater tendency for people to take to the streets," said Phelim Kine, senior Asia researcher at New York-based Human Rights Watch. China had an estimated 180,000 protests -- or "mass incidents" -- in 2010 and the numbers have risen steadily since the 1990s, according to estimates by sociology professor Sun Liping of Tsinghua University in Beijing. But the government has grown more sophisticated in handling them since the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, when soldiers fired on protestors, Kine said. "They have made the calculation that it is better to allow people a measure of active, public protest as a way to let people blow off steam," Kine said. However, the government still targets protest leaders, seeking to dissuade them using soft and hard tactics, he added. In the Songjiang case, Shanghai authorities have allowed the protests to take place, amid a massive police presence, but have not sought to clear away demonstrators with mass detentions. In the May demonstration, police blocked protestors from marching to the nearby university district, fearing greater student participation. In the smaller June protest, organisers held a dialogue with authorities, which allowed the demonstration to take place as long as it remained orderly. But the local authorities have not yet given any signal of giving in to the protesters. "Trust us, we will be spending so much money that there's no reason for us not to make sure it operates properly and safely," Xu Qiyong, an official of Songjiang's sanitation bureau, told the state-backed Global Times newspaper. But trust remains an issue. "There is no transparency. There is no confidence in the government," one protester said.