Christo, conceptual artist who wrapped the Reichstag – obituary

Christo, who has died aged 84, was the Bulgarian-American conceptual artist best known for wrapping the Reichstag in Berlin in nearly 25 acres of silvery polypropylene fabric and nine miles of rope for two weeks in 1995.

With his French-born wife and collaborator Jeanne-Claude (and then alone after her death in 2009), Christo (real name Christo Javacheff) occupied a unique position in contemporary art, undertaking eye-catching monumental wrapping-up exercises and other huge, if ephemeral, projects across the globe.

Refusing any sponsorship, saying it would limit their freedom, they funded their projects from sales of Christo’s drawings, collages and scale models – so profitably that their strategy became the subject of a case study compiled by the Harvard Business School. In 2018, the drawings and collages of one of Christo’s projects were priced at between $100,000 and $900,000. Christo, as one interviewer observed, was probably the only renegade artist to have a line of credit from a Swiss bank.

Their projects included putting up 3,100 giant 20ft-high blue and yellow umbrellas in Japan and in California (where one of the umbrellas blew over and killed a tourist), and wrapping, variously, a mountain in the Rockies, a swathe of Australian coastline, a 24-mile-long fence in California, a series of islands off the coast of Miami (in shocking pink), 176 trees in Switzerland and the Pont Neuf in Paris.

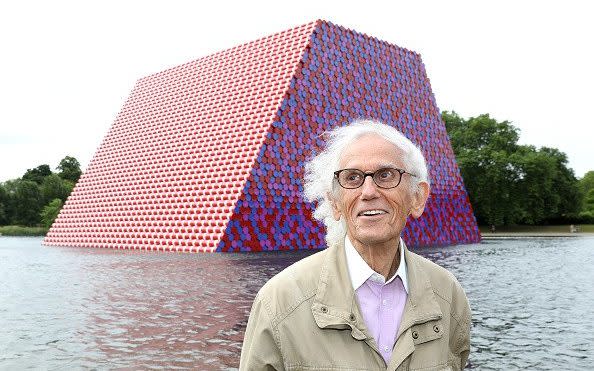

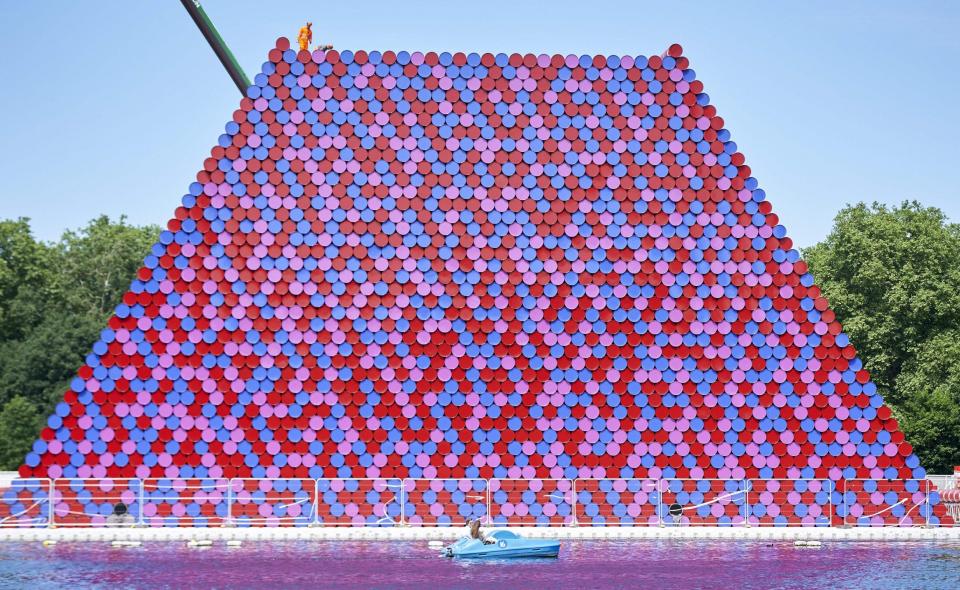

In Britain in 2018 Christo created The Mastaba, a work which involved balancing 7,506 painted barrels, with a combined weight of 500 tons, on a floating platform in the middle of the Serpentine in Hyde Park, where it remained for a couple of months before being dismantled.

Christo’s monumental wrapping-up projects provoked fiercely conflicting opinions, and not all came to fruition. Over the River, a plan to suspend reflective, translucent fabric panels high above a seven mile stretch of the Arkansas River in Colorado, was cancelled in 2017 after a long legal battle by local residents and the election of Donald Trump.

Indeed Christo and Jeanne-Claude themselves were hard pressed to explain the significance of their work. Describing their $21 million 2005 installation, The Gates, consisting of 7,500 saffron-coloured fabric panels hung at 12ft intervals along 23 miles of footpaths in Central Park – a project involving 5,290 tons of steel, 60 miles of vinyl tubing and more than a million square feet of fabric – Jeanne-Claude called it “a work of art of joy and beauty, which by definition has no purpose, no useful function.”

Christo, meanwhile, claimed that the importance of their work lay less in the end product than in the planning and construction. “For me aesthetics is everything involved in the process,” he told the New York Times in 1972, “– the workers, the politics, the negotiations, the construction difficulty, the dealings with hundreds of people. The whole process becomes an aesthetic”.

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff was born on exactly the same day as his future wife, June 13 1935, in Gabrovo, in what was then the Kingdom of Bulgaria, the second of three sons. His father was a textile manufacturer while his mother was the secretary at the Academy of Fine Arts in Sofia.

By the time Christo was admitted to the academy in 1953, Bulgarian cultural life had been crushed under communism. Finding the dogmatic socialist curriculum stifling, in 1956 he used a connection at the academy to receive permission to visit family members in Prague. He was there when Soviet forces crushed the Hungarian uprising, and shortly afterwards he left the communist bloc for good, fleeing to Vienna after bribing a railway official to let him stow away on a freight wagon.

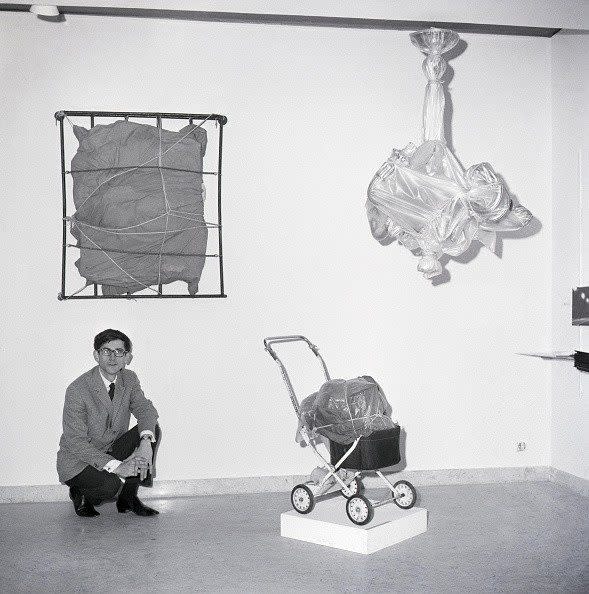

In Vienna, he stayed with a family friend, studied at the Vienna Fine Arts Academy, and was granted political asylum. He supported himself with commissions and, inspired by visits to art galleries in Switzerland, created his first “wrapped” work – a paint can, one of a series of wrapped household items that he called his “Inventory”.

In February 1958 Christo left for Paris, where he eked a living washing dishes and cars – and by painting conventional portraits of well-heeled Parisiennes to whom he was introduced by his landlord, the hairdresser Jacques Dessange .

Among his sitters were Brigitte Bardot (whose portrait he later wrapped in plastic) and the mother of Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon, the woman he married in 1962. They had a son and began their artistic collaboration, originally working under Christo’s name, but later crediting their installations to both “Christo and Jeanne-Claude”.

Christo had his first solo show in 1961 in Cologne, where exhibits included stacked oil drums and a wrapped Renault car inside the Galerie Haro Lauhus and a series of mysterious wrapped Dockside Packages on the quayside by the River Rhine. Some critics saw the works as an attack on consumerism, but Christo made no such claims.

In 1964 Christo and Jeanne-Claude moved to the United States, where they lived and worked in a converted former factory building in Manhattan’s SoHo district.

Their refusal to accept sponsorship enabled them to take a laid-back attitude to other people’s opinions, with the result that they often had trouble getting permission for their projects. The Reichstag wrapping project took 25 years to come off.

In addition, Christo always took the precaution of renting the space for miles around any given project, so that no one else, no matter how important or well-known, could piggyback on it. The Three Tenors wanted to sing and Claudio Abbado and Maximilian Schell wanted to have the Berlin Philharmonic play Fidelio in front of the wrapped Reichstag. All were turned down.

One of Christo’s most spectacular later works was a 2016 installation entitled The Floating Piers, consisting of 100,000 square metres of bright dahlia yellow fabric floating on 220,000 large polyethylene cubes on Lake Iseo, Italy, linking Monte Isola to the mainland town of Sulzano, and to a smaller island called San Paolo, in a 5.5km swathe held together with 220,000 matching screws, and kept in place by 190 anchors weighing five tons each.

“To be on The Floating Piers,” wrote Gaby Wood in The Daily Telegraph, “is both a privilege and a violation: a way of defying laws of nature we hadn’t realised we’d accepted so readily.”

In March this year Christo was given the chance to fulfil a long-held ambition when the Mayor of Paris gave him permission to parcel up the Arc de Triomphe in “25,000 square metres of silvery blue, recyclable plastic fabric and 7,000 metres of red rope”. Originally scheduled to open this Autumn, the project was postponed for a year due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Bronzed, white-haired and slim, Christo was a man of great charm and sunny optimism, fired by a belief that in the end things would always turn out well. He attributed his youthful nine-stone figure to eating raw garlic and yogurt every day for breakfast.

He is survived by his son.

Christo, born June 13 1935, died May 31 2020