Colombians displaced by civil war now in crossfire of drugs gangs

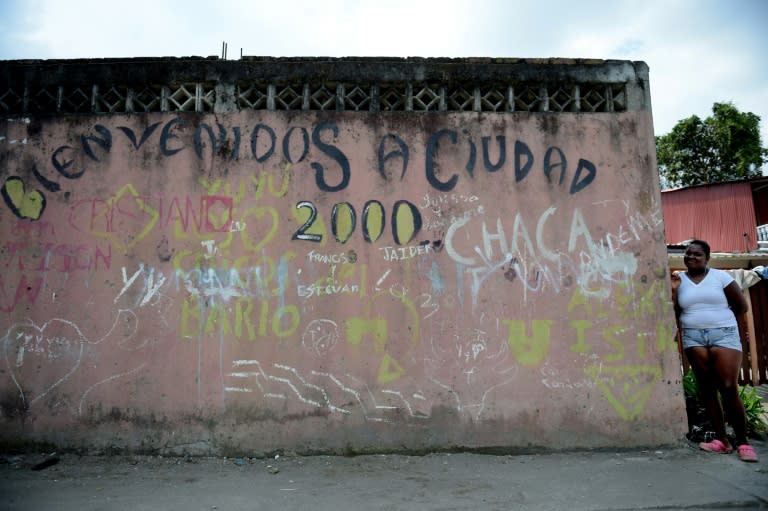

In the port city of Tumaco, the bullets are still flying a year after a peace deal ended Colombia's half-century civil war. The walls of its squalid houses are pocked by their impact, reminding those who once fled the conflict that there is still no respite from violence. People who were displaced by fighting between the army and the leftist FARC rebels are once again caught in the cross-fire, this time from drugs gangs carving out territory for lucrative cocaine smuggling routes along the Pacific coast. "They shot at our apartment. The baby was screaming in terror," recalled Marcia Perea, 47. The bullets drilled into the frame of the door that separates the living room from the bedroom and shattered her plastic chairs. Like other residents of her neighborhood, known as Ciudad 2000, the grandmother ranted about the shootings that have spread panic across Tumaco, a city of 208,000 people devastated by unemployment. Most of her neighbors had fled here to seek shelter from clashes in other parts of the country that, over more than 50 years of fighting, left around seven million people displaced from their homes. Their shacks are built over the fetid waters of a swamp and connected by a tangled web of rickety wooden bridges. "Tumaco is one of the epicenters of the conflict that continues in Colombia," said Christian Visnes, director of the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), which has been operating in Colombia since 1991. Situated on the border with Ecuador, this port city in the department of Narino sits atop one of the prize drug trafficking routes in the region, affording access for boats and submersibles to Central America and then north to the lucrative markets of United States. The dense jungle and coastal mangrove swamps make any oversight by the government difficult, despite the announcement last month that it was deploying 9,000 troops and police to tracks down FARC dissidents and other groups. - Murder on the rise - Tumaco is not the only strategic smuggling route for the cartels, but it is the area with the largest amount of land under coca cultivation in Colombia, which is itself the largest producer of cocaine in the world. It is here that all the links in the narco-trafficking chain come together. When the government signed a peace deal with the FARC one year ago, the number of grenade attacks -- a hallmark of guerilla activity in the region -- went down, said Jenny Lopez, a representative for the Defense of the People, a human rights group. Nonetheless, the much-anticipated peace did not last long. "What worries us now is the rise in homicides," she said. After the rebels -- who financed their military operations with cocaine trafficking -- downed their weapons and went home, other armed groups moved in to capitalize on their departure, triggering turf wars among rival gangs. Visnes, of the NRC, said there are now as many as 15 gangs vying for control of the lucrative drugs trade. Among other atrocities taking place in the city, Lopez recalled one Tumaco murder that was particularly grisly. "They cut off his head, his arms, they practically dismembered him and left him there." The coastline and the two small islands lying off it are crisscrossed with invisible boundaries, marking the territories of rival gangs. No one ventures out in the streets of some neighborhoods after a certain time at night. In Ciudad 2000 -- City 2000 in English -- a battle broke out recently between two gangs that lasted an entire weekend and forced 320 families to flee, said Lopez. - Tragic trigger - Between January and October, at least 2,665 people were forced to flee their homes in Tumaco, the NRC said. Without adequate shelter, the displaced families -- some from rural areas, some moving from one urban area to another -- arrive in "invasion sectors, where there are also armed groups," said Lopez. They cannot shake off the fear they live in. The peace deal stipulates that rebels who confess to their crimes, pay reparations to their victims and promise not to return to violence can receive alternatives to jail time for their wrongdoings. Arnulfo Mina, a vicar in the diocese of Tumaco, denounced the dozens of murders that have taken place here. In the past year alone, the number of homicides in Tumaco has been three times the national average: 152 victims, a rate of 74.5 per 100,000 inhabitants. "Coca is the trigger for all the problems here," said Mina, noting that the Pacific coast has historically been neglected by the rest of the country. He said even more trouble lay ahead "if the government does not have an aggressive plan for social investment" in Tumaco, where almost half the population lives in poverty, many of them without access even to safe drinking water. Once known as the "Pearl of the Pacific" for its beaches of dark sand and stunning coastal scenery, Tumaco looks more like a paradise at the gates of hell one year after the peace deal that was supposed to deliver the country from a half century of agony.