The history of the Group Representation Constituency

by Bertha Henson and Christalle Tay

SINGAPORE — You go to a restaurant. You have a choice between picking your dishes from the a la carte menu or going for the set. Think of the Group Representation Constituency as a set - with at least three and at most, six courses. There will always be a main course, which will be the leader of the GRC, usually a political heavyweight. There will always be dessert too, which could be kueh-kueh, lassi, or sugee cake.

The GRC scheme was introduced as an idea in the late 80s as a sure-fire way to get a non-Chinese into Parliament as an MP. The Government was worried that the majority Chinese population would pick someone of the same ethnic group if the electoral map only comprised single-seat wards. An older idea of "twinning a Chinese and non-Chinese'' would mean over- representation of the minorities. Then the GRC concept was fleshed out, after a long-drawn national debate which included representations made to a Parliamentary Select Committee.

Of course, it was a controversial issue, given that this marked the first time race was so openly discussed in Singapore. That, plus the argument that voting for a slate was a travesty of the one-man-one-vote system and was a ploy to handicap the diminutive Opposition further.

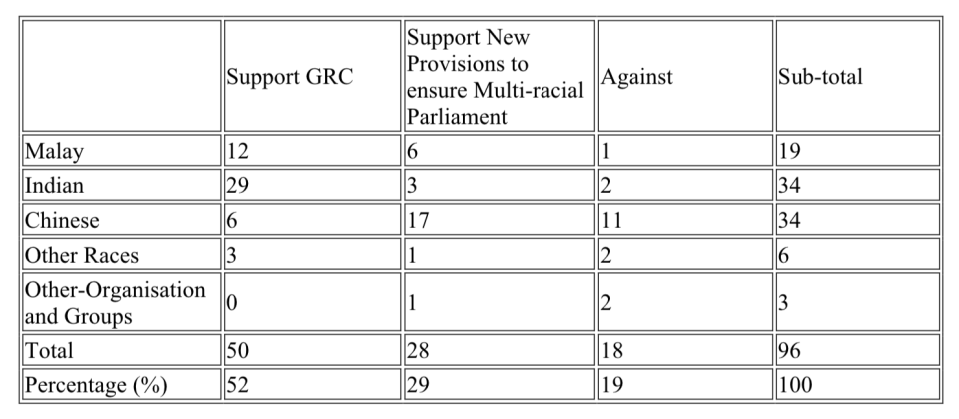

The committee, set up to investigate public support for the scheme and see if there was a better proposal to ensure multi-racial representation in Parliament, received 96 public submissions, with 50 supporting the GRC scheme and 28 supporting the need to ensure a multi-racial Parliament but with concepts other the GRC.

The following chart breaks down the distribution of the 96 public submissions by race and stance taken.

Source: National Archives of Singapore, the Report of the Select Committee on the Parliamentary Elections (Amendment) Bill [Bill No. 23/87] and the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment No. 2) Bill

Interestingly, one-third of the Chinese respondents did not support the GRC concept nor any moves to ensure a multi-racial Parliament.

The GRC marked one of the earliest of the Government’s activist ethnic policies to ensure that minorities have some form of representation. More recently, the same argument, supported by surveys, was made to establish a presidency that will always be rotated among the ethnic groups if one group has not been elected for too long.

Despite the misgivings of those who wanted race-blind representation, the GRC system worked in guaranteeing minority representation. In today's Parliament, it ensured at least 16 out of the 89 elected seats belong to MPs from minority communities.

Over time, the justification for GRCs was strengthened with the formation of town councils, which would achieve economies of scale if they managed a larger area. The bar was therefore set higher: opposition parties must not just be able to field the numbers if they want to contest in a GRC,m but were required to administer and manage a town as well. Later, another argument was made for even bigger GRCs which could form the boundaries of the Community Development Council, which are government-funded grassroots bodies introduced to help organise and lead smaller grassroots organisations. There are five CDCs in Singapore, each led by a PAP MP: South West, South East, North West, North East and Central.

The introduction of GRCs in 1988 (of three members each) led to a scramble among political parties to meet the minority requirement and to field enough candidates to stand in a GRC. The ground rules, literally, were changed with mergers of single-seat wards. Teams, which must include a Malay and an Indian/Other had to be fielded in wards that needed specific representation.

This meant that they had to collaborate with each other to maximise the effectiveness of the opposition’s limited number of candidates. Opposition parties Barisan Sosialis (BS) and Singapore United Front (SUF) merged with Workers’ Party (WP) in a bid to pool candidates. SDP and WP also strategised constituencies to contest in, with SDP candidates contesting in SMCs while WP candidates focused on GRCs. Both parties also agreed to avoid three-corner fights.

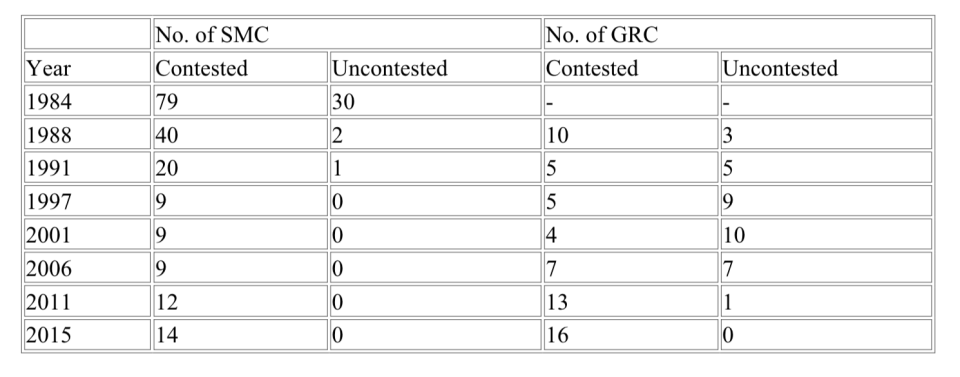

Source: Elections Department Singapore

Opposition parties struggled particularly in the elections from 1991 to 2001, when the minimum members in GRC started growing from the original three to a high of six. In 1997, nine out of 14 GRCs were uncontested. Out of the nine, four were six-MP GRCs and the remaining five were five-MP GRCs.

But if GRCs were supposed to close the Parliament door to the Opposition, SMCs still meant there was a window open. Besides Mr Chiam See Tong, then with the Singapore Democratic Party, retaining his Potong Pasir seat, WP chief Low Thia Kiang took Hougang in 1991. In the same GE, SDP took the SMC wards of Bukit Gombak and Nee Soon Central, bringing the opposition tally up to four.

That window, however, was shut and almost bolted in the following GE, in 1997. Constitutional amendments in 1997 raised the maximum size of GRCs from four to six, resulting in a dramatic decrease of SMCs as larger GRCs were introduced.

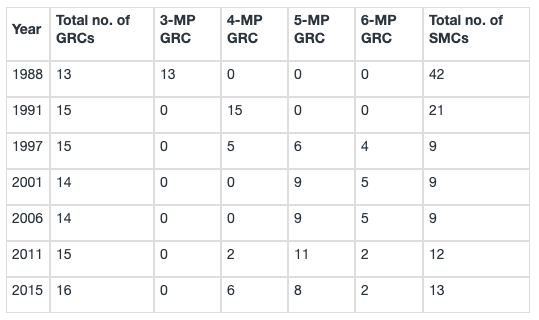

The number of SMCs was drastically reduced to nine, just shy of the legal minimum of eight. This reduction in the opposition’s chances, as they saw it, was coupled with the rise of jumbo GRCs. From a minimum of three MPs per GRC, a few GRCs were expanded to six MPs. The running joke then was how the whole of Singapore should be designated as a gigantic GRC. Three-MP-GRCs have gone into extinction, with the smallest GRCs constituting four members.

Source: EBRC reports (1988 - 2015)

Needless to say, there were criticisms that the Government was handicapping the Opposition by making it even more difficult to field such a large slate. The phrase “hanging onto the coat-tails of ministers’’ came into vogue.

The big GRCs had top ministers anchoring the ward. For example, the jumbo six-member Ang Mo Kio GRC is helmed by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. The conventional wisdom was that voters would not want to risk losing a minister by rejecting the PAP slate.

Since GRCs were introduced, no Cabinet minister has contested in a single-seat ward. Although the current Minister for Culture, Community and Youth, Ms Grace Fu, juggles a Cabinet minister appointment and Yuhua SMC, her appointment was only made on 1 Oct 2015 – after she was elected into the 13th Parliament. So will she stay on in Yuhua or be moved to the greater safety of a group?

There was also a question mark over whether the PAP was correct to say that non-Chinese candidates would have trouble getting elected if they stood in single-seat wards. There were two exceptions: PAP's Michael Palmer won in a three-cornered fight for Punggol-East against two Chinese opposition politicians, and PAP's Murali Pillai won 61.2 per cent of the votes against veteran politician Chee Soon Juan in the Bukit Batok by-election.

But the initial misgivings of the Opposition over the GRC scheme seemed to have been misplaced. In 2011, the WP swept up the five-member Aljunied GRC. The view that voters would not sacrifice a minister or other officeholders was extinguished. Then Foreign Minister Mr George Yeo, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office and concurrently the Second Minister for Finance and Transport Ms Lim Hwee Hwa, as well as Senior Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Zainul Abidin Rasheed – not quite a lightweight team – and two other members of the PAP team bowed out. The win was mainly attributed to the pulling power of WP’s Mr Low, who left the safety of his single-seat ward to lead the GRC team. It was a venture which paid off.

But it was not to be for veteran MP Chiam See Tong, who left his Potong Pasir seat for his wife to contest, and moved to fight in neighbouring Bishan-Toa Payoh GRC with four other members of the Singapore People’s Party. He lost the contest. So did his wife.

In 2015, the opposition parties proved nimble enough to adapt to the electoral changes, so much so that they were able to contest all seats for the first time ever. The PAP managed to wrest Punggol East from the Opposition and pared down the WP's share of votes in Aljunied GRC. There is now less talk about the GRC scheme being a handicap to the opposition, although there remains rumblings about whether the one-man-one-vote system has been compromised.

The PAP still has a GRC-linked card up its sleeve: Winning a GRC is not the same as being able to run a town council - and right now, the courts are looking into whether the WP did it right.

Bertha lectures in the National University of Singapore. Christalle is a final-year Communications and New Media Department undergraduate.

Related stories

COMMENT: Boundaries review committee formed...so now what?

PM Lee convenes Electoral Boundaries Review Committee

No formation of Electoral Boundaries Review Committee yet: Chan Chun Sing