Democrats Are Using An Old Playbook To Attack The Supreme Court And Fracture The Conservative Coalition

After the Dobbs decision, Democrats touted their legislation to reform the court by imposing term limits, requiring justices to abide by ethics rules, providing a legislative veto for certain decisions and adding four seats to the court. (Photo: Illustration: Damon Dahlen/HuffPost; Photos: Getty)

On Jan. 22, 1973, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Roe v. Wade that women have a federal right to an abortion. Nine days later, Minnesota Republican Rep. John Zwach introduced the first constitutional amendment in Congress to overturn the decision.

In the years that followed, attacks on the court — and abortion rights — served as key party-building tools for Republicans as they put together the conservative electoral coalition that came to dominate American politics.

Where Roe helped conservatives build that coalition, the court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturning Roe presents Democrats with the opportunity to pull at its seams, and to do so with some of the same fusillades against the Supreme Court.

Two weeks after the court’s decision, Democrats introduced a flurry of legislation aimed at reversing the decision and protecting other rights, including same-sex marriage, same-sex relations and contraception access, after Justice Clarence Thomas said the court’s prior decisions granting them should be overturned too.

House Democrats promptly passed legislation legalizing abortion nationwide, preventing states from banning interstate travel by abortion seekers or the importation of medication abortion through the mail, protecting same-sex marriage and legalizing contraception access. Only the law protecting same-sex marriage appears to have a shot at passing the evenly divided Senate as Republican elected officials are almost entirely unified against legal abortion.

While those bills didn’t directly target the court, but rather the practical outcome wrought by its decision in Dobbs, some other pieces of legislation were aimed right across First Street. After the Dobbs decision, Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee touted their suite of procedural legislation to reform the court by imposing term limits, requiring justices to abide by ethics rules, providing a legislative veto for certain decisions and adding four seats to the court.

“Probably none of them are going to pass, but that’s not the point,” Dave Bridge, a Baylor University political science professor who has written about the political role of legislative attacks on the court, said about all court attacks levied by Democrats.

House Democrats lead an abortion rights protest in front of the U.S. Supreme Court Building on July 19, 2022 in Washington, DC. (Photo: Anna Moneymaker via Getty Images)

The point of the procedural attacks is to tarnish the legitimacy of the court. Meanwhile, issue-based attacks on the abortion bans that followed from Dobbs play a political role that historically has been used to build durable political coalitions, most recently by the conservative movement that overturned Roe.

“The best place to look would actually be to Roe v. Wade, and how Reagan played his cards right and used that decision to build the Republican coalition,” Bridge said.

Cracking The New Deal Coalition

The Republican Party became dominant with Reagan’s victory in the 1980 election by following the model of successful dominant political coalitions of the past. They cobbled together groups representing minority populations across the country in order to form a majority coalition.

In American history, similar majority coalitions include the Jeffersonian Republicans, Jacksonian Democrats, Lincoln’s Republicans and FDR’s New Deal Democrats. These coalitions become dominant when their electoral success ensured that the policy priorities that unified their majority together were fixed into national law and culture and lasted for decades.

The Supreme Court’s political role in these majority coalitions is “to confer legitimacy” on both “the particular and parochial policies of the dominant political alliance” and “the basic patterns of behavior required for the operation of a democracy,” political scientist Robert Dahl wrote in his seminal 1957 essay on the political role of the court.

Or as political scientist Robert McCloskey put it in his 1960 study of the court’s political role: the Supreme Court “seldom strayed very far from the mainstreams of American life and seldom overestimated its own power resources.”

The court’s ensuing decisions on school prayer, the treatment of criminal defendants, school desegregation and abortion tested the theories of Dahl and McCloskey as they were, at the time, not only counter to mainstream public opinion, but pitted members of the dominant New Deal coalition against each other.

These decisions prompted a response in the form of issue-based attacks on the court that helped Republicans break apart the New Deal coalition and put together the majority coalition that would supplant the Democrats’ New Deal coalition with Reagan’s 1980 election.

The attacks on the court levied by conservatives from the 1950s through the 1980s served three different purposes, according to Bridge and his Baylor University political science colleague Curt Nichols, in their papers “Congressional Attacks on the Supreme Court: A Mechanism to Maintain, Build, and Consolidate” and “Court Curbing via Attempt to Amend the Constitution: An Update of Congressional Attacks on the Supreme Court from 1955–1984.”

They were made to “maintain coalitional cohesion, build a new majority, or consolidate recent victories,” Bridge and Nichols write. Each of these purposes can be demonstrated throughout the enervation of the New Deal order and the rise of Reaganite conservatism.

The New Deal political order unified a diverse array of groups including union members, Northern and Western white liberals, Catholics, Blacks and Southern segregationists around the common pursuit of policies that allowed strong federal government involvement in economic affairs from industrial investment, regulation, worker empowerment and antitrust enforcement.

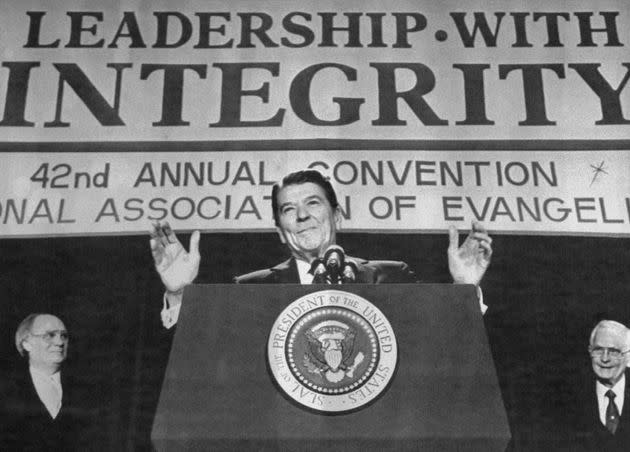

President Ronald Reagan speaks to the National Association of Evangelicals where he called for passage of amendments to outlaw abortion and make prayer a part of the school day for public school students. (Photo: Bettmann via Getty Images)

By the early 1950s, the New Deal’s unifying economic priorities were safely enacted into law and the Supreme Court, made up solely of justices appointed by Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, conferred legitimacy on them as well. Dissension emerged once the court began to side with affiliated coalitional groups in conflicts that pitted them against other coalition members.

This began with the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education that found the racial segregation of public schools to be unconstitutional. Racial equality was a goal pursued by white New Deal liberals and Black voters, but it pitted them against Southern segregationists wedded to a policy of white supremacy. One year later, Southern segregationist Democrats consistently attacked the court with jurisdiction-stripping bills aimed at prohibiting the court from deciding cases related to the administration of state education systems.

These attacks, according to Bridge and Nichols, “helped southern Democrats maintain coalitional cohesion … by trying to redirect the Supreme Court away from pursuing liberal second-order preferences, attacks contributed to the political effort to slow the implementation of Brown, and obstruct the federal government from desegregating ‘with all deliberate speed.’”

‘The Larger Share Of The Pie’

Beginning in 1962 with the court’s decision in Engel v. Vitale banning prayer in public schools, attacks on the court increasingly came from Republicans. Engel was deeply unpopular with both Catholic voters, who were a sizable voting bloc in the Democrats’ coalition, and Southern white protestants, already incensed over the court’s desegregation rulings.

Instead of the attacks levied by Southern Democrats to keep their coalition together, Republican attacks sought to “build a new majority” by showing they sided with affiliated New Deal groups angered by the court’s decisions.

Such attacks, like the constitutional amendment to overturn Engel introduced by New York Republican Rep. Frank Becker on the day the decision came out, “contributed, in previously unrealized ways, to the slow-motion breakup of the New Deal coalition,” Bridge and Nichols argue.

The court’s decision in Roe accelerated that breakup.

In a memo prepared for President Richard Nixon, his advisor Pat Buchanan wrote that abortion was “a rising issue and a gut issue with Catholics.”

“[F]avoritism toward things Catholic is good politics; there is a trade-off, but it leaves us with the larger share of the pie,” another memo prepared for Nixon stated.

Nixon shifted his abortion position to attract Catholic votes prior to the court’s decision in Roe, but it would be Reagan who reaped the full political benefits.

“The response to Roe was a necessary part of the Reagan Revolution,” Bridge said. “Roe wasn’t sufficient, but Roe was necessary.”

Roe was “the tipping point,” Bridge added, because, “It creates single-issue voters and also it’s the last straw for socially conservative Democrats like Southern Democrats and Catholic Democrats.”

Where Catholics once accounted for between one-third and one-half of Democrats’ vote share, Republicans won 61% of the Catholic vote in 1984, Bridge and Nichols note.

Democrats And Dobbs

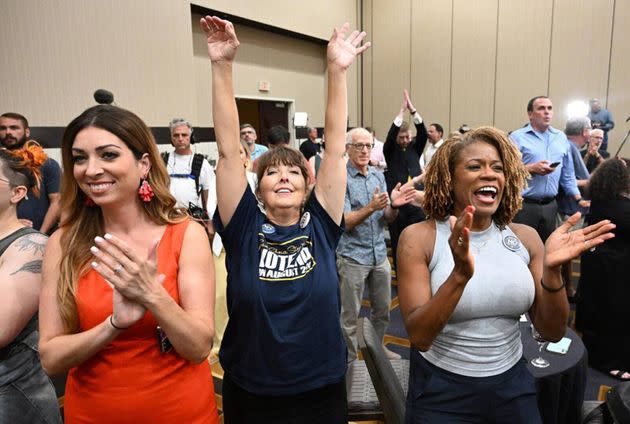

Calley Malloy, left, Cassie Woolworth and Dawn Rattan applauded the failure of a ballot initiative on Aug. 2, 2022, that would have taken away abortion rights in Kansas. (Photo: Tammy Ljungblad/Kansas City Star/Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

Now the shoe is on the other foot.

Polls consistently showmajorities above60% are opposed to the court’s decision to overturn Roe while popular support for the court has dropped dramatically. Sixty-one percent disapproved of the court in a poll by Marquette Law School. Fifty-three percent told Gallup they disapproved of the court, the highest level recorded in the 21st century, while a record low of 25% said they had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the court.

“There are more pro-Roe Republicans than there are anti-Roe Democrats,” Bridge said. “The share of the pie is bigger for Democrats.”

Twenty-three percent of Republicans and 54% of independents self-identify as pro-choice while only 10% of Democrats self-identify as pro-life, according to Gallup.

The court, just as it did in the 20th century, moved from legitimating the policy concerns that brought a majority coalition together, like undoing the New Deal economic order, to enacting the preferences, like banning abortion, of coalitional groups, like the religious right, that are unpopular and expose divisions in the coalition.

Support for federalism and an opposition to high taxes and federal government intrusion in the market held the GOP coalition together. That fits nicely with arguments against the federal government’s role in ending Jim Crow, desegregating public institutions, taking affirmative action to combat racial prejudice or secularizing public life. But once in power, Republicans prioritized tax cuts and supply-side free market reforms over all other policies as these were the first-order priorities of the coalition.

Since the majority coalition could not, or did not want to, enact the second-order preferences that divided their coalition through legislation, they put the energy for those preferences into judicial nominations, where they could be enacted without electoral considerations.

“Part of the story all through the Reagan-Bush era was that Republican presidents were balancing their opposition to Roe with electoral considerations,” said Thomas Keck, a political scientist at Syracuse University who studies the political role of the court. “But the judges — Neil Gorsuch or Samuel Alito — couldn’t care less about those political considerations. They are more committed to a particular ideological vision of the Constitution than they are to the short-term electoral fortunes of some Republican senator.”

The American public’s position on abortion may be far more nuanced than just pro- or anti-abortion, but with Roe gone, Republicans are now the ones who have to defend policies that the public does not support including the failure to provide exemptions for rape, incest or the mother’s health; limiting care to mothers who might be harmed or die from childbirth; prosecuting women and doctors; banning out-of-state travel for abortions; and policing the mail for FDA-approved abortion medication.

“The big takeaway is the campaign message, which is that Supreme Court attacks can be a site on which you can enlarge your coalition,” Bridge said. “They don’t have to work. You don’t have to pass attacks. You don’t even have to follow through on promises to make changes to the Supreme Court. You can use it as a winning issue, and winning elections is the ultimate currency in American democracy.”

Democrats and abortion rights supporters have already seen success in the landslide victory for abortion rights in Kansas on Aug. 2.

Rep. Hank Johnson (D-Ga.) touts legislation to add four seats to the Supreme Court after its Dobbs decision overturned Roe v. Wade. (Photo: Tasos Katopodis via Getty Images)

They are now pouring money into campaign ads tarring Republican candidates at every level of government for supporting Dobbs and backing unpopular anti-abortion policies that can now actually be enacted into law. Democrats have spent at least $31.9 million attacking Republican candidates on abortion, more than six times that spent by Republicans, in the 50 days since the Dobbs decision according to The New York Times.

But even if Democrats can successfully maneuver to take political advantage of Dobbs as Republicans did of Roe, the Supreme Court remains a unique problem.

A Minority Court

Democrats have won the popular vote in eight out of the last nine presidential elections, but the court is stacked with six justices appointed by Republicans.

“Most of the time through the court’s history the process of judicial selection has kept the court within the main lines of public opinion and political support, but that process seems to have broken down,” Keck said.

The three nominees who proved pivotal in overturning Roe — Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett — were all appointed by a president who lost the popular vote. They were also confirmed by the votes of senators representing a minority of the American electorate. They are the first three justices to hold the honor of both such distinctions. The only other justices in history similarly confirmed by senators representing a minority of the American electorate, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, are also on the court.

“That is quite unprecedented and striking,” Keck said. “It helps explain the situation that we are now in.”

And it helps explain the introduction of procedural attacks on the court like those adding seats to eliminate the conservative majority. By targeting the legitimacy of the court, these reform proposals aim to influence the court’s behavior.

“If this six-justice majority persists for the time being, then a big part of the story is going to be about what divisions emerge,” Keck said.

These court reform proposals also act as a marker at the start of a debate over the court’s role that will only grow stronger if the conservative supermajority continues to issue decisions that stray far from mainstream opinion.

And if Democrats’ issue-based attacks on the court over Dobbs end up working as Republican’s attacks over Roe did in the 20th century, the court will find itself even more unbalanced from the expressed democratic will of the people. Every prior moment when the court has found itself out of line with popular sentiment, it has faced attacks on its legitimacy and calls for reform. And every time it has eventually wound up in line with popular opinion, at least on the unifying goals of the dominant political coalition.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.