‘It depends on your politics’: Georgia’s uneven reopening breaks along party lines

The BeltLine is a former railway turned nature trail that loops 22 miles through Atlanta, and it’s been crowded with walkers and cyclists since Georgia relaxed its short lived shelter-in-place on 1 May.

But the masses have largely stayed away from the BeltLine’s shopping crown jewel, Ponce City Market, as many of its stores chose to remain closed, despite the crippling economic hardship caused by the shutdown.

“I don’t think it’s as much as like turning on and off the light switch, as much as it’s ‘What’s going to ensure the sustained viability and success of our tenants long term?’” says Michael Phillips, president of Jamestown Properties, the Market’s developer.

Related: Trump's push to reopen US risks ‘death sentence’ for many, experts warn

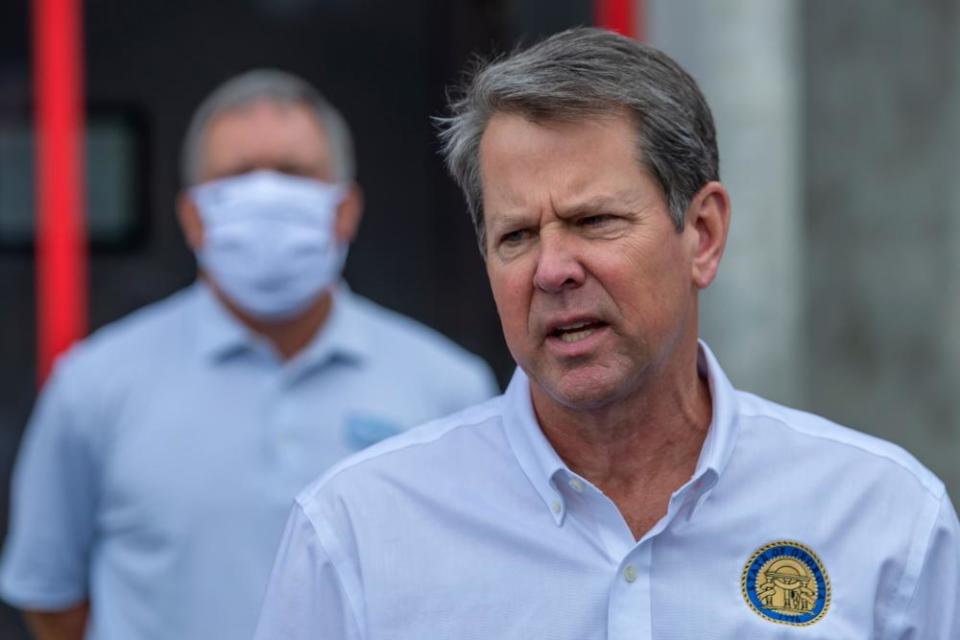

Georgia, helmed by Republican governor Brian Kemp, has been at the forefront of the reopening movement in the US, to the cheers of anti-lockdown protesters and the horror of many public health experts. As America watched, Georgia’s gyms, churches, hair and nail salons, and tattoo parlors were allowed to reopen in late April, with mandates of social distancing. A week later, all other gathering spots – except bars, nightclubs and live performance venues – were allowed to open too.

Photograph: Erik S Lesser/EPA

But far from reopening in full, Georgians’ embrace of their freedom from lockdown has been a patchy affair, with business owners and their customers only tentatively emerging from their homes, as the pandemic still rages in much of America.

Fears of a second coronavirus wave remain, amid reports of erroneous data releases by the state and a lag in the reporting itself. The result is that some Georgia residents venture out and businesses tentatively open, while many others remain closed. The pattern of reopening seems to mirror the political divides of the state.

Many businesses in predominantly liberal-leaning communities, similar to the one where Ponce City Market is based, have resisted the easing of restrictions. In downtown Decatur, one of the most liberal-leaning towns in the state, a number of storefronts are still shuttered in its idyllic square.

“The White Bull will be temporarily closed due to social distancing. We look forward to opening again soon,” the White Bull restaurant announces on its site in late May. “Stay safe, stay healthy.”

Another staple, Sweet Melissa’s, has been closed since March.

But other neighborhoods are flinging their doors wide open, ready to return to life before the coronavirus. Atlantans are seeing a rift: uneven re-openings across the city, at times based on the faultlines of their communities as Georgians wait to see if their lives can return to normal.

“I live in suburbia in north Atlanta, and the attitude up there about this whole thing is completely different,” says Brian Maloof, the owner of Atlanta restaurant Manuel’s Tavern, as he watches a regular eat a hamburger under an outdoor tent near his restaurant on CCTV.

“It is completely dependent upon your political philosophy, on whether or not you’re going to open and throw the doors open and everything is fine, or if you’re going to be more cautious about it.”

But the economy is flickering back to life.

Around Mother’s Day, as restaurants welcomed people to celebrate, Holeman and Finch, one of Georgia’s largest bakeries, saw an increase in sales, reaching a pandemic high of 10% of normal business.

The wholesale bakery’s goods, found in approximately 300 restaurants statewide, are delivered to only half of its partners nearly a month after the governor lifted the state’s short lived shelter-in-place, and at a small fraction of its usual profit, says the company’s director of business operations Brittany Brown.

But the damage is done, and the road back looks hard as fears of the virus – or its return – remain. The company has let go more than 80 employees in the past two months, and recently asked 14 to return to work. Only four showed up, Brown says, many of them unable to make it back to work because public transportation has not returned to full capacity. One employee told her he would have to walk eight miles each day, in between various legs of public transport, to get to work right now. He wouldn’t be able to return to work, he told her.

But even as employees have the go-ahead to return to work, it doesn’t mean they or their employers are open for business. The Georgia department of labor announced Thursday that more than 2m regular initial unemployment claims have been processed in the past 10 weeks – more than the 1.7m claims filed over the last five years combined.

More than 40,000 Georgians have tested positive for coronavirus since 1 February, with no downward trend of cases that the governor projected while announcing his plans to revive the economy at the end of April. Instead, a misleading chart was posted on the public health department’s website showing a steady decline in cases over two weeks, with the dates out of order, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

“I have said from the very beginning that we are making decisions based on data, science and the advice of public health officials like Dr Toomey,” Kemp said at a news conference Thursday, referring to the head of the public health department. “We are also committed to full transparency and honesty as we weather this healthcare crisis.”

The chart has since been taken down. Georgia’s Republican governor was one of the last to declare a shelter-in-place and the first to lift the order. According to the state’s own data, the numbers are ping-ponging on the chart, similar to a plateau, rather than a decline, three weeks after restrictions eased.

As the numbers fluctuate, by the state’s own additions and miscalculations, Georgians watch those numbers weary and impatient to return to their daily rituals.

Recently, Maloof, the owner of Manuel’s Tavern, received a call from a group who had been meeting at his restaurant for nearly three decades. They wanted to meet inside, they begged him, asking him to make an exception for them as he served dozens of others takeout only. He relented by cordoning off space for his loyal customers, making space for the group.

On the day he opened for them, he counted the people in a corner of his restaurant, the ones who came through the door.

“Only eight were willing to come inside,” Maloof says. “It was very telling to me how much fear there is, and how much concern is still out there.”