Did a coronavirus cause the pandemic that killed Queen Victoria's heir?

The epidemic spread with startling speed. It appeared first in London and within weeks had swept Britain. Thousands died of respiratory illness, the prime minister was laid low, and employees’ sickness disrupted industry and transport.

It sounds familiar. Yet this epidemic erupted in 1891 when waves of disease swept round the globe, eventually killing more than a million people. The outbreak was later attributed to flu and dubbed the Great Russian Flu pandemic.

However, a group of Belgian scientists has since argued that the pandemic was caused by a different agent: a coronavirus. “It’s a very convincing analysis,” Dr David Matthews, a coronavirus expert at Bristol University, told the Observer. “The scientists used very sophisticated, advanced research and their claim is worth taking seriously.”

The study was led by Belgian biologist Leen Vijgen and her team’s results were published in the Journal of Virology several years ago. Their work, which has re-emerged with the appearance of Covid-19, suggests the coronavirus linked to the 1890 outbreak is likely to have leapt from cows to humans before spreading worldwide. In the case of Covid-19, it is thought bats were the source of the virus.

The Vijgen argument is based on the close genetic match between the human coronavirus OC43, a frequent cause of the common cold, and another coronavirus that infects cows. By studying mutation rates in the two viruses, researchers concluded they probably shared a common ancestor from around 1890, indicating the virus jumped from cows to humans at that time. Thus, that year’s epidemic “may have been the result of interspecies transmission of bovine coronaviruses to humans,” the researchers say.

Many 1890 patients suffered central nervous system damage – rare in influenza but common in today's Covid-19 pandemic

This link was suggested in 2005 - making the researchers look extraordinarily prescient. “This is a very careful piece of work,” said Matthews.

Observers have pointed out that many 1890 patients suffered central nervous system damage – a relatively rare symptom for influenza but common in the Covid-19 pandemic.

Another striking feature of the 1890 disease was the observation that men were far more vulnerable than women, another feature shared with Covid-19. At the time, one senior doctor recalled how he had been astonished to arrive at morning surgery in January 1890 to find more than 1,000 patients – the majority of them men – clamouring for treatment.

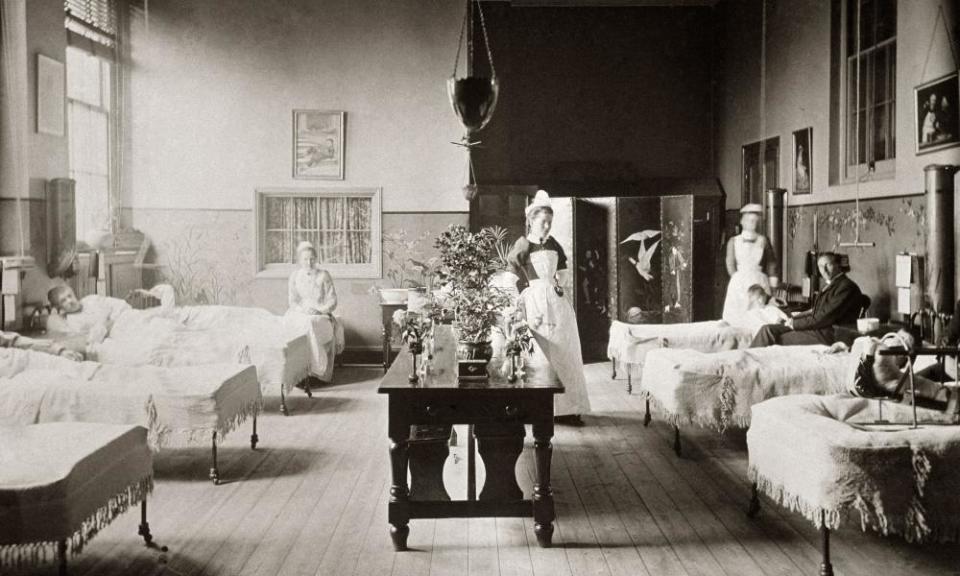

Humanity has had time to live with OC43 which today only causes relatively mild illnesses. By contrast the 1890 pandemic – like Covid-19 today – had a dreadful initial impact. The first cases were reported in late December 1889 and thousands of people died over the next six weeks. Courts were closed, several senior politicians became seriously ill, including Lord Salisbury, the prime minister, while telegraph and railway operations were disrupted when large numbers of workers fell ill.

The most famous victim was Prince Albert Victor, Queen Victoria’s grandson. Prince Eddy, as he was popularly known, contracted the disease during a New Year’s shooting party and on 14 January, after five days with pneumonia, he died aged 28. He was second in line to the throne and his death changed the line of succession. The Queen’s grandfather George, Albert’s younger brother, was crowned instead.

At the time the cause of the epidemic sparked serious medical divisions. The existence of a virus – an entity so tiny it would have been invisible even through a microscope – had yet to be established by scientists, and epidemiological thinking was dominated by miasma theory. This claimed that weather or fluctuations in the upper atmosphere created toxic air that poisoned humans.

“However, such theories could not explain why isolated communities such as lighthouses, jails and monasteries, which were presumably exposed to the same occult influences, escaped the epidemic or why the influenza appeared to attack cities and densely populated urban centres close to railways and roads before spreading to rural areas,” notes medical historian Mark Honigsbaum.

The initial 1890 outbreak subsided after six weeks. However, the disease returned the next year and caused nearly twice as many deaths and also reappeared in 1892. The Registrar General calculated the death toll in 1890 as 27,000, in 1891 as 58,000 and in 1892 as 25,000.

These second and third waves are worrying given that we are still in the first outbreak of Covid-19. Honigsbaum expresses caution, however. “The claim that the ‘Russian influenza’ pandemic could have been due to a coronavirus is intriguing, if speculative. Certainly, one of the pandemic’s key features was the way it attacked the nervous system, sparking remarkable cases of depression, psychosis and insomnia.” One notable victim was another prime minister, Lord Rosebery, who was laid up for six weeks in 1895 with a crippling fatigue.

“There were also frequent relapses,” adds Honigsbaum. “These suggest a first attack did not necessarily confer immunity, something scientists suspect may also be true of coronaviruses.”