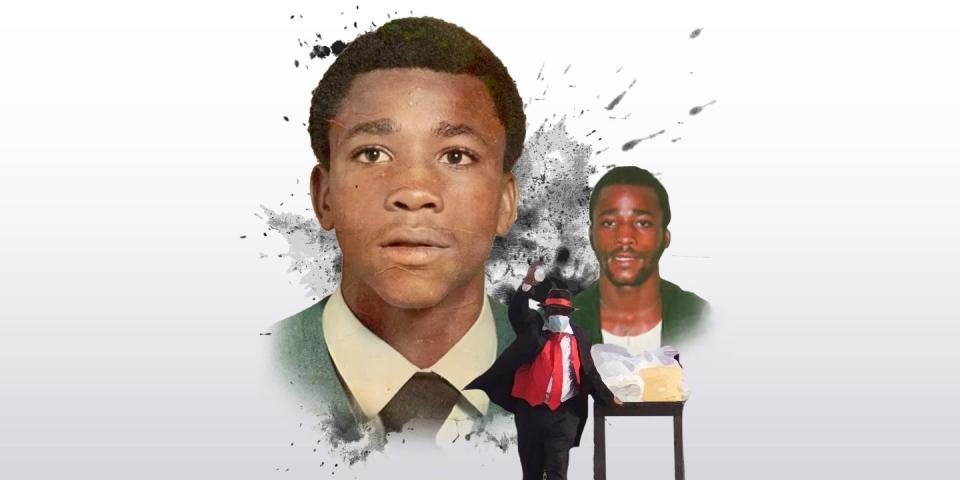

He Did Not Commit the Crime. Yet He Served 44 Years in Prison.

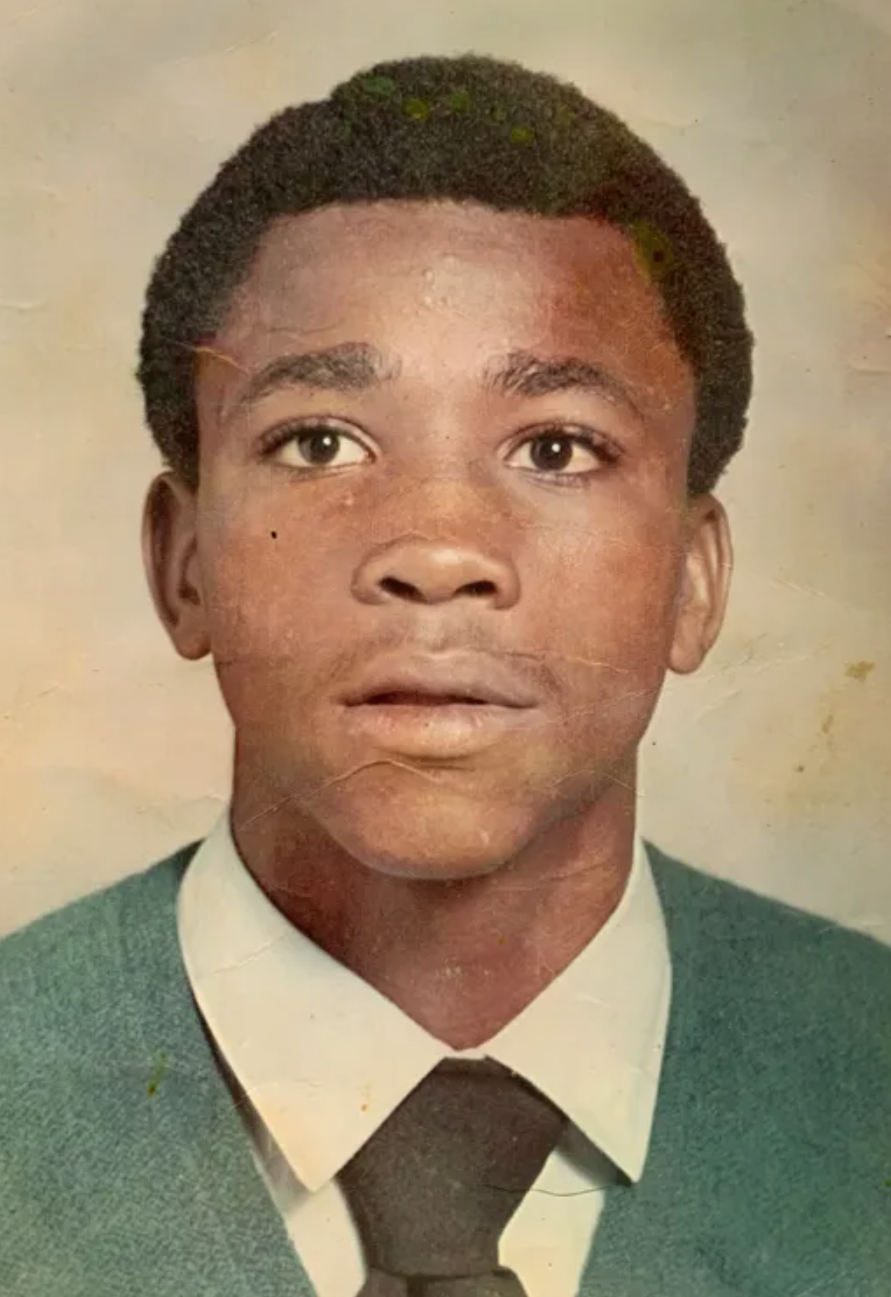

The mood at the courthouse in Concord, North Carolina was tense. Ronnie Long, 20, a Black cement mason, was on trial for the rape of Sarah Bost, 54, a wealthy, white widow. All summer, protesters had demonstrated against Long's arrest, accusing police of racial bias. Now, hundreds were gathered outside for the verdict in a case that had torn the community apart. Inside, tensions were even higher. Virtually every spectator on the defense's side was Black; everyone on the prosecution's side, and all twelve jurors, were white. When Long was declared guilty, the audience erupted, and police rushed to clear the courtroom.

That was in October 1976. This past August, Long was exonerated and walked out of prison a free man. He'd been locked up for forty-four years, placing him third on the list of American prisoners who've served the longest sentences for crimes they did not commit.

Since 1989, when DNA was first used in the United States to prove a prisoner's innocence, more than 2,650 inmates nationwide have been exonerated. Altogether, that's 24,150 years lost to wrongful convictions. And those are just the cases that the system has been forced to acknowledge.

I first became involved in criminal justice reform in the early nineties, after reading about a case in the news that highlighted the inherent unfairness of mandatory minimums. I've always despised injustice of any kind, and it wasn't long before I focused my efforts on wrongful convictions. I am the founding board member of the Innocence Project, a nonprofit started by Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld that has helped secure exonerations for hundreds of people nationwide, including more than twenty who were on death row. I sit on the boards of several more likeminded organizations, including Families Against Mandatory Minimums and the Drug Policy Alliance. In 2016, I launched a podcast on which I interview men and women who've been wrongfully convicted. It's called, appropriately enough, Wrongful Conviction. I've spoken to more than a hundred guests, and Ronnie Long stands out for the singularly grave miscarriage of justice he suffered. (You can listen to his episode here.)

When we spoke, Long was still incarcerated at Albemarle Correctional Institute, in North Carolina. He didn't know then that he'd be released in a little over a month. The country was convulsing in the wake of George Floyd's murder, which brought renewed attention to the pervasive racism of the country's institutions, perhaps none more so than our criminal justice system.

To no one's surprise, people of color make up a disproportionate number of exoneration cases. Thirteen percent of the U.S. population is Black, yet Black prisoners comprise thirty-nine percent of the male prison population and forty-seven percent of those proven to have been wrongfully convicted.

This is one wrongfully convicted Black man's story.

One evening in April 1976, Sarah Bost was in the home she'd shared with her deceased husband, an executive at one of the largest employers in the Charlotte area, when a man broke into her home, held a knife to her throat, and demanded money. He dragged her across the room, tore off her clothes, beat her, then raped her. She fought back, she'd later tell investigators, scratching him so hard that her fingernails bent backward. The phone rang, startling the attacker; he got up and ran out the front door. She ran to a neighbor, who called the police.

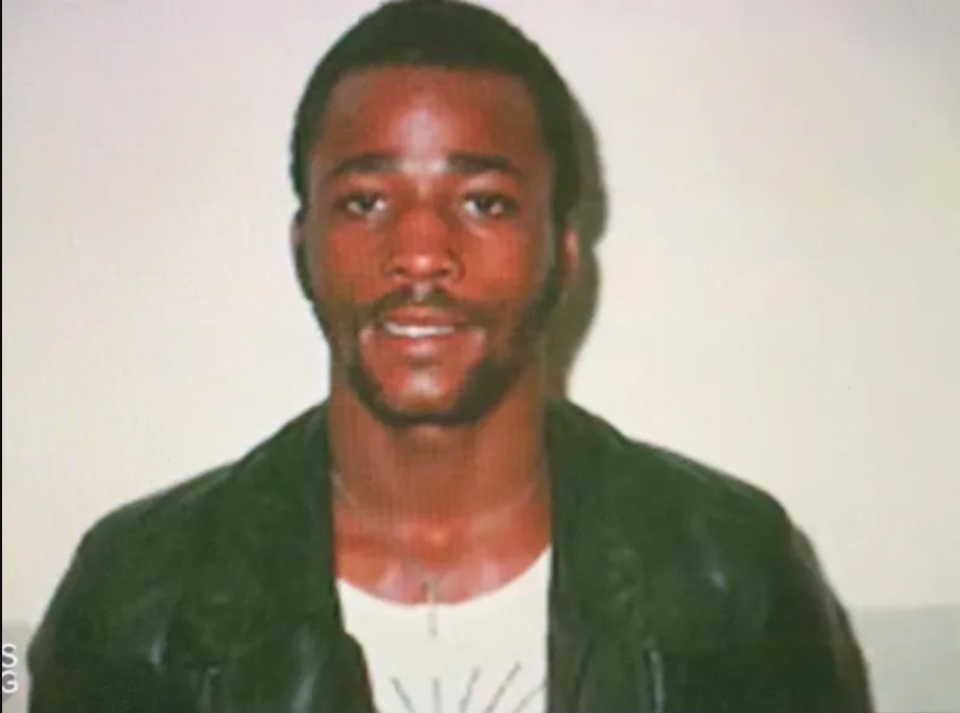

Bost told the police that the man was Black—"yellow-black," she said, according to court documents, meaning light-skinned—and wore a cap and leather coat. The next day, officers presented Bost with photographs of thirteen suspects. None of them looked like the attacker, she said.

Nearly two weeks later, police asked her to join them at the courthouse because, they said, the man who raped her might be present. Scared that he'd see her, she wore a disguise—a red wig and glasses—and sat in the gallery. Of the fifty or so people in the courtroom that day, twelve were Black, and Ronnie Long was one of them. He happened to be wearing a leather coat, and was seated in the middle of the gallery the entire time Bost was surveying the crowd. Still, it took her ninety minutes to identify him as her attacker, and only after the judge called him to come forward on an unrelated trespassing charge (which was later dropped). That evening, May 10, 1976, Long was arrested.

Notwithstanding the highly suggestive and inherently unreliable way in which he was identified, the case against Long never added up. His skin is dark, not "yellow-black." Bost had described the man as clean-shaven; at the time, Long had facial hair. He had a leather coat, but there were no scratches on it or on him. And he had an alibi: At the time of the attack, Long was across town, at his parents' house, where he lived, on the phone with the mother of his 2-year-old son.

Not one shred of forensic evidence tied him to the crime scene. This isn’t because no evidence was available. In fact, police did a thorough sweep of Bost’s home. They took hundreds of photographs, collected strands of hair as well as samples from the carpet and the wall paint, and lifted a partial shoeprint from the front porch. A sexual assault kit was collected from Bost, but there's no record that it was ever tested, or that it even still exists.

The outcome was determined before the trial even began. Physical evidence be damned, Long would be convicted, and he'd be punished to the fullest extent of the law. At the time of his arrest, there was only one possible sentence for a rape conviction in North Carolina: the death penalty.

Prosecutors dangled a plea deal so generous that it might well have called into question the strength of their case: Admit guilt, they told Long, and he'd receive a seven-year sentence, with the possibility of release on bail in just three years. Despite the overwhelming odds against him, and the fate he faced if convicted, Long turned down the offer. “My dad looked at me and told me, 'I didn’t raise ya’ll to admit to something you didn’t do'," he would later tell a reporter. "So I didn’t take the plea. I went to trial.” On October 1, 1976, the all-white jury—drawn from a pool of prospective jurors handpicked by the sheriff, four of whom had professional connections to Sarah Bost's husband—declared Long guilty of first-degree rape and burglary.

If Ronnie Long struck upon any luck at all during the ordeal, it's that he narrowly escaped state-mandated execution: Between his arrest and his conviction, the Supreme Court had struck down North Carolina's wildly broad death penalty statutes. He got two life sentences instead.

By 2005, Long was represented by the Wrongful Convictions Clinic at Duke University. That year, his lawyer requested evidence from the rape kit that had been collected from Bost, only to find out that the kit was missing. Even worse, he discovered that the forensic evidence collected at the crime scene, which had shown no ties to Long, had been withheld from the defense during trial. Though the revelations made Long's case for exoneration undeniable, he'd spend fifteen more years behind bars.

In August of this year, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth District finally asked a lower court to hear the motion for relief that Long’s defense attorneys had been seeking. Shortly thereafter, Ronnie Long was exonerated.

The court's decision effectively doubled as a searing condemnation of our criminal justice system. “What is it about us that we want to prosecute and keep people in jail when we know evidence might exist that might lead to a different outcome?” Judge James Wynn, asked during a virtual hearing in May. “Why is that so offensive to us now that we want to protect illegal activity from forty-four years ago?” He continued, “When did justice leave the process such that we let our rules blind us to the realities that we all can see?”

On August 27, 2020, Ronnie Long walked free. He wore a three-piece suit for the occasion. He was greeted by family and supporters, including his wife, Ashleigh, who'd met him when she was a criminal justice student at the University of North Carolina. Twenty years old when he entered the correctional system, Long is sixty-five today.

In late October, I called him to catch up, and to find out how the first two months of life on the outside have been. “It’s complicated out here," he told me. He's struggled to enroll in Medicare, and to find a bank that will allow him to open up an account. For a man who missed the personal computer revolution, let alone the internet, today's technology has taken some getting used to. "Things have advanced so much since 1976," he said. "But it's all good."

He remains deeply disappointed in the institutions that took away so much of his life. “If the people in the judicial system in North Carolina had a righteous bone in their bodies, it wouldn’t have taken forty-four years for me to prove my innocence," he said. "That’s why I put all my legal documents online so everyone could see what they did to me.” You can view them on freeronnielongnow.org.

Long credits the media with bringing the attention to his case that caused the state to pay attention. “The media was my voice to the masses," he said, "and it’s because of the media that I’m free."

Cases like Long's are the reason why I will never stop fighting to right the wrongs that are all too frequently wrought by our cruel and capricious criminal justice system. Entrenched institutions aren't about to start correcting themselves, especially not if they can so easily get away with it. As long as brave people like Ronnie Long continue standing up to the powers that be, despite the odds against them, it behooves each and every one of us to do our part to amplify their stories and fight for lasting change.

Check out Wrongful Conviction with Jason Flom here, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

You Might Also Like