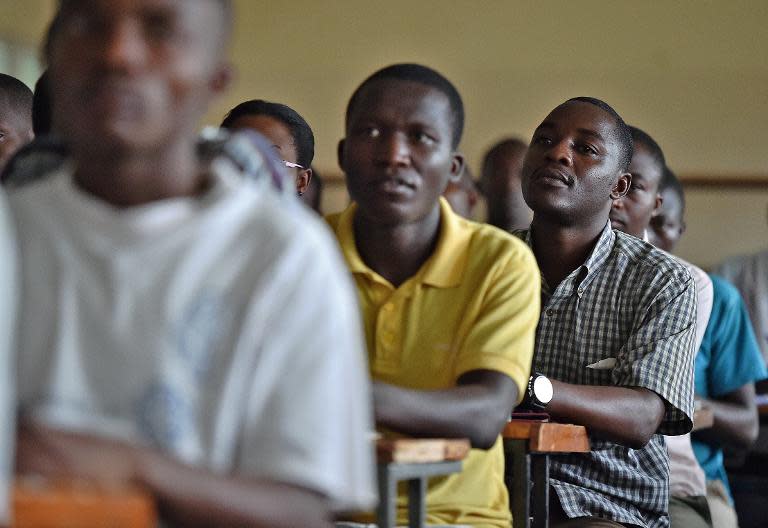

Economy in the dumps, Burundi students hunger for change

Like most students in Burundi, Serge Claver Nzisabira can barely make ends meet, even when he shares a miniscule two-room address with four others in a Bujumbura suburb. All five of them struggle to keep up with their rent, which eats up their meagre monthly scholarship of 30,000 Burundian francs (about $19 / 17.5 euros). They share only two mattresses, one of which was fully occupied by a roommate in the throes of a malaria attack. "In 2012, when I arrived here, life was a little more affordable than today," said Nzisabira, aged 25, a student of English at the University of Burundi who comes from the southern province of Makemba, a poor rural area. Nzisabira said that in the past few years, the price of rice has gone up by 50 percent, and he is now forced to get by on just one meal a day. Burundi, a small nation of hills in central Africa's Great Lakes region, is one of the continent's most densely populated and poorest countries. With elections approaching in June and current President Pierre Nkurunziza seeking to stay put and enjoy a disputed third five-year mandate -- despite a constitutional limit of two terms -- the appalling economic situation has become a burning topic. Burundi scores badly on nearly all indicators. Among key ones, per capita Gross National Income is just $260, life expectancy is 54, and 67 percent of people eke out an existence below the poverty line, according to World Bank figures. Agricultural production is not keeping up with population growth and the country is heavily dependent on foreign aid. Endemic corruption worsens such bad tidings. Burundi ranks 159th out of 175 nations on Transparency International's corruption index, and has been labelled the most graft-ridden country in the region, despite tough competition. Few senior officials pay any taxes, anti-corruption activists say, while opacity prevails when it comes to the awarding of lucrative state contracts. - 'An explosive situation' - According to Faustin Ndikumana, a protest group leader trying to lobby the government to tackle high prices, Burundi's current predicament is unsustainable. "The situation is explosive because of the economic problems, but the authorities seem unwilling to address these problems, not even to engage in a dialogue," he said. In February, students went on strike to protest over yet another delay in the payment of their grants. This coincided with a call for a general strike called by Ndikumana's movement against the high cost of living. "Students are not the only ones who are poor. Everyone is behind them," said Gilbert Niyongabo, an economics professor at the main university. The financial woes come on top of mounting complaints of a government campaign of repression driven by Nkurunziza's desire to hang on to power. The political crisis has raised fears that worse is yet to come for the landlocked country, still recovering from a brutal 13-year-long civil war that ended in 2006. Burundi lies in a region beset by genocide and chronic insurgency by a multitude of arm groups. It has a Hutu majority and a Tutsi minority like its small neighbour Rwanda, where Hutu troops, police and militias slaughtered 800,000 people, mostly Tutsis, in 1994. Student Nzisabira, however, insists that he and his classmates are not looking for a major confrontation with the authorities and that the strikes are always an absolute last resort. "Really, the strike is the final step after our allowances arrive late," he said, explaining that absences from studying mean courses are completed in five years rather than four, prolonging their poverty. But regarding the forthcoming polls, he signalled that Nkurunziza cannot take an election win for granted: "We want leaders who will solve the problems of the students."