The Effects of Childhood Sexual Abuse On Mental Health

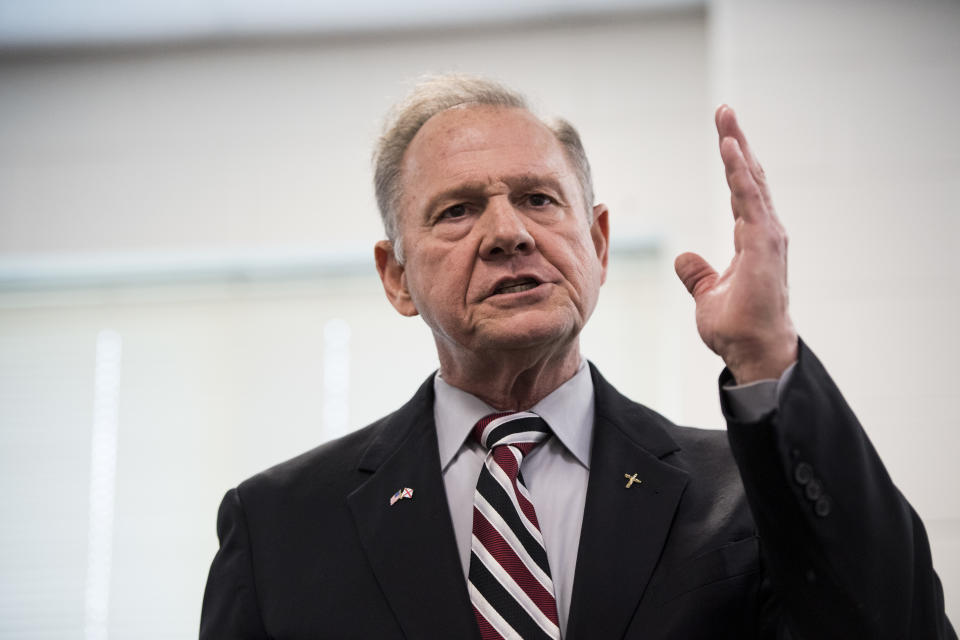

When Beverly Young Nelson described the fear and powerlessness she felt as a 15-year-old girl who, she asserts, was groped and assaulted by GOP Senate candidate Roy Moore decades ago, it resonated with Sylvia Goalen, a 37-year-old survivor of childhood sexual abuse.

Like Nelson, Goalen kept what had happened to her a secret for years, fearful that her abuser had the power to hurt her and her family.

Nelson knew that Moore was the local district attorney. He told her that if she came forward, no one would be believe her. Goalen — who was molested by a teenage cousin from ages 8 to 10 — was living in Guatemala at the time, and her parents were working on migrating to the United States. Her cousin threatened that if she came forward, no one would believe her and she would not be allowed to move.

But it wasn’t just the fear and secrecy that felt familiar. Goalen also saw her own story mirrored in the account of Leigh Corfman, now a 53-year-old customer service representative. Corfman told The Washington Post she felt “responsible” for Moore pursuing her, at one point driving to her home and undressing her. Corfman and Nelson are two of nine women who have now come forward with accusations against the Republican candidate.

“[It] set the course for me doing other things that were bad,” Corfman told the Washington Post, adding that she began drinking and doing drugs in the years following the incident. She attempted suicide when she was 16 years old.

This lifelong sense of being “tainted,” or carrying a legacy of shame — along with behavior or choices that are informed by this feeling — will sound familiar to many adults who faced sexual assault in childhood or adolescence.

“What we know from studying adverse childhood experiences is that it can impact an individual’s long-term mental and physical health and well-being,” Laura Palumbo, communications director for the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, told HuffPost, “as well as their economic well being and even their life expectancy.” Research suggests that children who are exposed to multiple forms of trauma have reduced lifespans by up to 20 years.

While the occurrence of sexual violence in childhood by no means consigns a person to a particular destiny, studies have shown the health effects can be — and often are — profound and far-reaching. The substance use and suicidal tendencies that Corfman described align with a robust body of research on childhood sexual assault victims in later life.

Goalen, who now works as an advocate with Darkness to Light — a nonprofit dedicated to preventing child sexual abuse — says that once her family moved to the United States, the assault stopped, but its effects did not.

“I didn’t care much about my body. I was very promiscuous growing up,” she told HuffPost. “I graduated with great grades, but I personally abused my body when I was younger.”

Goalen snuck out at night, drank too much and experimented with drugs. Emotionally, she says, she just felt numb.

“Childhood sexual abuse correlates with high levels of depression, anxiety and eating disorders,” Palumbo said.

Again here, the studies are plentiful — though of course, not all victims of childhood sexual abuse go on to grapple with mental health issues. Investigations have shown that children who are sexually abused are at greater risk of developing PTSD, that women who are sexually abused as children are more likely to have a major depressive episode, and that they go on to have greater lifetime prevalences of conditions like obsessive compulsive disorder and agoraphobia. They are also more likely to attempt suicide and to engage in self-mutilation than women who did not experience childhood sexual abuse.

Research has also shown that adults with a history of abuse — sexual or otherwise — are at higher risk of chronic health conditions or symptoms.

According to a 2003 review, those conditions include (but are not limited to): severe headaches, back and stomach pain, fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia. Another study, which tracked women who’d experienced sexual assault in childhood for more than two decades, found they had increased rates of obesity and major illness. There is evidence that women who are subject to moderate or severe sexual or physical abuse in childhood are at much greater risk of developing diabetes as adults, and even cancer.

Goalen, for her part, battled thyroid cancer earlier in her 30s, and while she does not believe the sexual abuse she suffered in childhood directly caused the disease, she wonders if years of mistreating her body due to the abuse finally caught up to her.

Indeed, the link between childhood trauma and poor physical health outcomes in adulthood is complex. People who are abused in childhood are more likely to engage in behaviors like drinking, smoking and riskier sexual behaviors, which subsequently increases their risk of developing certain illnesses and conditions. A 2003 study on the connection between adverse childhood experiences (which includes sexual abuse) and liver disease found that the kinds of behaviors a person engaged in were a major mediating factor.

Goalen, for example, says that although she eventually got her life more in order and now has a successful career with her local county government, she has struggled with her weight her whole life. She sees it, at least partially, as one outcome of growing up feeling somehow separate from — and betrayed by — her own body.

“I’ve been on a diet since I was 10 years old,” Goalen said. “I never thought I was skinny enough. I’ve always thought something was wrong with me.”

Experts do believe, however, that there are physiologic mechanisms that contribute to long-term physical consequences from childhood sexual abuse, too. For example, the researchers behind the 2010 study on sexual abuse and diabetes believe it’s possible the link stems from physiological changes to a person’s stress-response system.

“The research has really showed that the body doesn’t effectively ‘metabolize’ trauma,” said Palumbo.

Of course, there are limits to the research available today, not least of which is the ability of studies and investigators to parse the specific outcomes associated with specific forms of abuse at specific points in a person’s life. There is also the issue of retrospective bias, Steven Meyers, a professor of psychology at Roosevelt University and a Chicago-based clinical psychologist, told HuffPost.

“It is much easier for researchers to find adults who are receiving psychotherapy or other services and then ask whether they were abused as children,” Meyers said. “This approach, though, excludes childhood abuse survivors who do not experience symptoms or who may not be receiving services as adults. Larger studies, of which there are fewer, can include variables such as age at abuse, duration and frequency of the abuse, relationship to the perpetrator, and gender of the victim and the perpetrator.”

These are nuances the research must tackle, Meyers said.

In the meantime, when we think of these incidents — and even try to write them off as decades-old and therefore irrelevant, as some Moore supporters have said — it is essential to contend with the evidence that for some victims, they contribute to lifelong hardship and struggle. And even if that hardship and struggle is not outwardly obvious.

“What happened to me ... ” said Goalen, breaking into quiet tears. “I’m still dealing with the consequences.”

Also on HuffPost

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.