‘It’s all my fault’: How I killed Jack Reacher

Lee Child, wildly successful thriller writer and creator of Jack Reacher, has come clean: he’s retiring. In fact, he retired around the middle of last year, after completing Blue Moon, his most recent book. He didn’t start the following book – as he has been doing religiously for the last 20 odd years – on 1 September. The next one, The Sentinel, will still appear though. Out this October, it’s written by his kid brother, Andrew, formerly known as Andrew Grant, now re-baptised “Andrew Child”.

But the original Reacher is dead. I mourn him. But I killed him. His publishers, Penguin Random House, thought I would. Turns out they were right. It’s all my fault. Me and possibly Tom Cruise too. Maybe Reacher was already on his last legs anyway, but we finished him off.

I first fell in love with Jack Reacher over 10 years ago in a little indie bookstore in Pasadena, California, down the road from Caltech. I picked up a paperback at random. The Enemy. All about some hardcore, 6ft 5in, 250lb military cop dishing out rough justice to all and sundry. Not my usual fare, but there was something distinctive about the voice – moody, muscular and yet melancholy, like a Miles Davis solo. I bought it, read it (I was supposed to doing something else entirely) and then read another Reacher. And another. I was hooked.

When a new Reacher came out, I reviewed it for The Independent. Sometimes, after you write a review, authors will write in to complain; on this occasion, uniquely, the author wrote to me and thanked me for it. Lee liked a particular line in it, where I had described Reacher as “a liberal intellectual with arms the size of Popeye’s”. Before long I was interviewing him in London, and then again in New York. By 2014 I had read all 19 Reachers, some of them in hardback. Like any decent addict, I was already wondering where my next fix was coming from.

Which explains why it was that, in August of that year, when I had the crazy idea of trying to write a book about somebody writing a book – but in real time, simultaneously, up close and personal, to actually sit and watch a writer write a novel from beginning to end – the first author I thought of was Lee Child. It could have been Marcel Proust or James Joyce or Albert Camus, but they were dead. It could have been Donna Tartt, but she was so slow (around 10 years per book) that I could be dead before she finished. Whereas Lee, I knew, knocked them out regular as clockwork, one a year. So I emailed him, very tentatively, to ask: would you mind if I look over your shoulder for a year while you’re writing the next Reacher?

Nothing could have surprised me more than the reply I received: “I’m starting the new one Monday, so if you’re serious, you’d better get over here.” It felt like fate knocking at the door, so I got on a plane to New York and knocked on his door on the Upper West Side the following Monday, 1 September. He was probably amazed that I had turned up, but since I had, he had to go through with it.

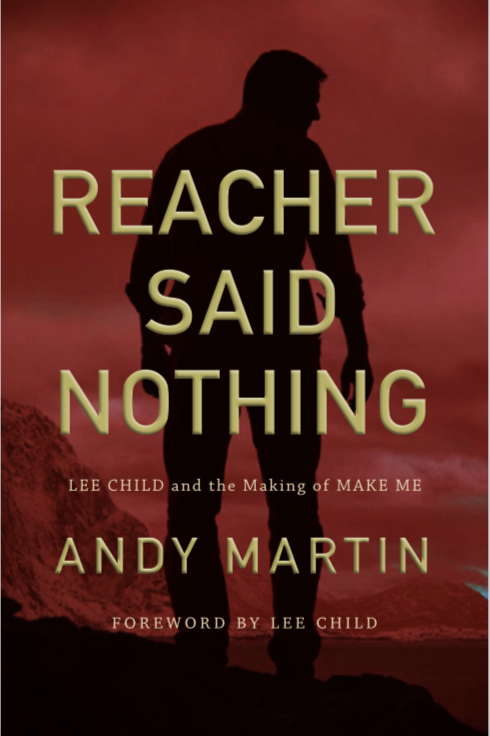

So for months on end, I watched Lee write his 20th novel in the Jack Reacher series, Make Me. I sat perched on a couch a couple of yards behind him, taking notes for the book that would become Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of “Make Me”. The rule was that I started when he started and finished when he finished. I couldn’t sneakily go about rectifying and polishing; he didn’t, so I couldn’t. The line of his that still echoes in my brain, even now, is: “This is not the first draft – it’s the only draft.” That sounded as if Jack Reacher were writing a novel: nobody was going to mess with his prose.

And that, of course, was my fundamental error: to confuse the writer and his hero. Perhaps, to be fair, there is a bit of Odysseus in Homer, a bit of Madame Bovary in Flaubert and, likewise, a bit of Jack Reacher in Lee Child. As Lee himself said, recalling his days brawling in the school playground, “Reacher is me aged nine”. Do they not share the same birthday (29 October)? Both drink absurd amounts of black coffee. They’re both tall. But Lee is barely more than half Reacher’s weight. More of a stick insect. Fold him up neatly and you can fit him into one of Reacher’s arms. As he once said, in shorts he looks like Olive Oyl.

Again, Reacher: takes the bus, of no fixed abode. Child: private jets and houses in several countries. And a Renoir and an Andy Warhol on the wall. Despite all of which, I still tended to think of Lee in terms of Reacher, the vigilante, nomadic outsider, drop-out and avenging angel. Oddly enough, I think I may have been the first to explain to Lee the blindingly obvious, namely that he was all the bad guys he had ever dreamed up as much as he was Jack Reacher. The horrible Hook Hobie, the seductive and sadistic Lila Hoth, the monstrous Little Joey, they were all alter egos. “You evil mastermind bastard!” I blurted, when he finally worked out, several months after Make Me’s first page, exactly what horror was going on in the tranquil small town of Mother’s Rest.

It came as a bit of a shock to him: that he was the bad guy, not just the good guy. But the irony of the situation I found myself in was that, according to some (OK, many), I was the bad guy. A lot of people assumed that I would put Lee off his stroke. One guy I met in a New York bar told me flat out: “You are killing Jack Reacher!” (He also said I was a pervert and a voyeur.)

Coleridge blamed “the Person from Porlock” for messing up his great poem “Kubla Khan”. The Reacher publishers were even more explicit: they called me “toxic” and wanted Lee to stop talking to me. I get this. From the point of view of the publishers, they were the lucky owners of a golden goose, laying regular golden eggs – did anybody really need an egg inspector? Wasn’t there a risk he might upset the goose? Or cause him to stop laying?

Over 100m

Books sold worldwide by Lee Child

I had trespassed into the inner sanctum, the holy of holies, the very room in which the great man was working. In their eyes, I had committed a mortal sin.

As far as I was concerned, I was basically a guy in a white coat. This was a semi-scientific experiment. What could possibly go wrong? I was an anthropologist studying a primitive tribe, which happened to consist of just one man. Lee referred to our relationship as a kind of Stockholm syndrome, but whether I was holding him hostage or the other way round was unclear. He and I both scoffed at the word “toxic”. As if I could be some kind of poison! This was a guy who smoked a packet of Camels a day and an occasional pipe of hashish: he must be immune to having a fly on the wall watching him. And yet, looking back, I now wonder if all the doubters, fearing for their hero’s welfare, did have a point. (Not too many people worried about my welfare. I was exposing myself to a lot of second-hand smoke, which really was toxic.)

Lee’s job was done, I thought, the day he pressed send and delivered his file to the publishers. I stopped when he stopped. But I had been exclusively focused on the writing process (as had he, of course). It took a few months for me to get the blinkers off and realise that the book didn’t even exist at that point. It hadn’t been published, and hardly anyone had read it. I was definitely the first to read it (if you exclude the writer), and I believe I hold the record for the slowest ever reading of a Reacher, given that I couldn’t read any faster than Lee could write.

I spoke to a woman in Stockholm who had read the entire Lee Child oeuvre in the record time of five weeks

But that left out the whole business of printing and publishing and marketing and selling and reviewing and reading the book, when it really existed, rather than as a file on a computer. So I had to go back and write the book that would become With Child: Lee Child and the Readers of Jack Reacher, in which I became, this time perhaps, a real anthropologist with the immense tribe of loyal Lee Child readers – the “Reacher creatures” – in my sights.

I got to meet the real woman, living in San Antonio, who had bought the right (at a charity auction) to have a character named after her in Lee’s book, and whose life turned out to be uncannily like the fiction. I spoke to a woman in Stockholm who had read the entire Lee Child oeuvre in the record time of five weeks, driving herself and her entire family mad in the process. There was only one reader, who lived in the backwoods of Montana, who reckoned he was tougher than Reacher – in fact he considered Reacher to be a “lightweight”, an urban sophisticate who would not survive in the wilderness. But then again, he had a habit of dousing himself in elk urine (for the purpose of attracting other elks) and had invited Lee to go bear hunting with him (Lee politely declined). Another reader, in South Africa, found that Reacher was a perfectly acceptable substitute for her recently deceased husband.

Meanwhile, Lee carried on writing the next one, Night School (a classic MacGuffin narrative involving a stolen suitcase), beginning on 1 September, as ever. But there was a significant shift. Whereas in Make Me the horde of really rather evil citizens in Mother’s Rest were largely anonymous (“the guy in the post office”, “the guy in the rubber shop”, “the guy with the hair”), Wiley in Night School not only had a name but a whole backstory – and even shared several characteristics with Reacher himself, including wearing the same or similar clothes. Lee, having realised that he was the bad guy as much as Reacher, felt he had to make him just a bit more sympathetic than usual. He also sped the whole thing up, in comparison with Make Me, turning it into more of a film script.

This was partly because I was no longer watching him quite so closely, but it probably had more than a little to do with Tom Cruise.

From the very first, the Reacher novels are literary artefacts (Steve Cavanagh, author of Thirteen and Twisted, has called Lee Child “the greatest writer on the planet”), but they are also eminently filmable. Yet while the film rights sold, no movie was made until Tom Cruise came along and made One Shot into Jack Reacher (2012), with none other than Tom Cruise playing the title part. Lee got so much flak for that – as if he had chosen Cruise for the part – that it even spilled over onto me. I began to receive threatening messages, intended for Lee, saying stuff like: “Go to hell, Child, you sold us out!” (at the more polite end of the spectrum). There was a sizist element in all this: Reacher was huge, hulking, an exemplar of hegemonic masculinity; Tom was not. And let me apologise right now for once comparing the two of them, in print, to the Empire State Building on one side of the street and Dunkin’ Donuts on the other.

There has been something subtle going on in the writer’s psyche. He had to give up writing because he realised he was no longer Reacher

Size had nothing to do with it. They just had different skill sets. Tom specialised in driving (or piloting a plane/helicopter or riding a motorbike at high speed) and running; his best films were like a long chase scene. Reacher was useless at driving and running; he was just too damn big to fit in a car anyway. Reacher was more of an inaction hero, a thinker, perfectly happy to stroll around town and have seemingly pointless conversations or sit and have a haircut and the like, pausing only for occasional bloody fight scenes or casual carnal encounters. The film, although not terrible, was not great. The Reacher novel was always an exercise in mythic realism; the film was neither that realistic nor mythic.

And now Tom was making a second movie, Never Go Back (2016), based on the 18th book in the series. Lee was messing around down in New Orleans shooting his cameo appearance; he’d had one in the first film too. Probably unwise if he didn’t want people to identify him with the movie versions of the books. He stuck to a line: “The last time I looked at the book, the words were exactly the same in the same order.”

They were the only ones he had written. Everything else was Hollywood. But the reality was he was going to be ascribed responsibility regardless. I once asked him: “Why don’t you make the films yourself? You’ve got enough money, buy a studio or something.” His answer: “I’m too used to being a lonely writer in a back room: I couldn’t get on with enough people for long enough.” But the fact is that he had started to think about taking back control. His job title at the TV company Granada (before he got sacked and became a writer) was “controller”. He didn’t like being out of control.

I freely admit it was my fault too. Just as his shrewd publishers feared, I had succeeded in gentrifying him

Lee had a final three-book contract to fulfil. He was seriously thinking of hanging up his boots after book 21, but then they offered him “ridiculous” money to do more. Lee was always honest about the amount of money he was earning – far more honest than any writer I’ve ever come across. He even showed me a cheque once (it was for $28.72, residuals from Paramount Pictures for one of his token appearances). “I’m 100 per cent art and 100 per cent commerce,” he once said.

His plan, after being given the push from Granada, was always to pay off the mortgage and support his family. He did that. He has earned at least £100m, probably more like £200m. But the writing wasn’t all about the money. He had a tone and a style and a soul that defied mere materialism. A whole set of aesthetics and perhaps even ethics. There was a precarious equilibrium between art and commerce that he sustained while writing Make Me. But if he was going to shift his balance, it was only ever going to be one way. In the direction of business.

Why did he run out of steam? The easy answer is that he was lured away by television money to Amazon Prime. Which is doubly ironic considering he used to – very publicly and repeatedly – heap scorn on Amazon for what they had done to the book market and independent bookstores around the world. They still have to find the right guy to play Reacher. Tom is out. They are now looking for “the biggest guy we can find”.

But it seems to me that there has been something more subtle going on in the writer’s psyche. He had to give up because he realised he was no longer Reacher. Which, of course, is stupid, because he never was Reacher in the first place. But, for the space of 20 or so books, it was possible for him to dream of himself as the hero. A saviour figure. Reacher was always a lone wolf, an outsider, a “Meursault with muscles” as I once wrote, thinking of Camus’s hero.

Lee hated, as he would say, “the big guys”, and took sides with the victims, the powerless, the weak and the infirm. But Lee had himself become one of the big guys. In particular, there was only ever a Camel cigarette paper between him and his Penguin Random House publishers (Transworld in the UK). He had become part of – a rather dominant part of, Mr Big himself – an organisation, a system, a gang, not dissimilar in structure to the mafias that Reacher so despised.

Lee hated to plot and plan. He preferred to write in a rough, spontaneous, improvisatory way, making it up as he went along. But then he got caught up in the plotting of publishers to snare yet more readers and sell yet more books. The whole point of Reacher was to vanquish the plotters and their subterranean conspiracies. Lee used to deride the “PR bullshit” of his own publishers, but he finally bought into it. It was bound to happen. Maybe anyone would have done the same, but it spelled the end of Reacher. Lee realised that he had finally become the bad guy.

I freely admit it was my fault too. Just as his shrewd publishers feared, I had succeeded in gentrifying him. I took him seriously as a writer, something he had never done. It would have happened anyway, but I legitimised him, gave him quasi-academic respectability. He went from being a chancer, an opportunist, a rebel, a Birmingham boy who had cracked it, to an upstanding member of the literary establishment.

Handing Reacher over to his younger brother Andrew is a nice touch. And generous too. But back when I was hanging out with him, there was never any question of passing on the baton. He always said he would only let someone else write Reacher over his dead body. They could do it after he was dead, he said, because then he “wouldn’t care”. But, for a while at least, he cared. He twice turned down offers from the Fleming estate to have a shot at the Bond franchise. He compared literary resurrections of Stieg Larsson’s Lisbeth Salander or Jason Bourne to the half-decomposed zombies of Stephen King’s Pet Sematary. You could do it, but was it worth it? Clearly the publishers thought it was, and Lee ultimately went along with their scheme. You can retire, but Reacher can’t.

And so a new Child is born. Andrew Child, né Grant, the accomplished author of Run and Invisible, and most recently Too Close to Home, now has a great character to go with his undoubted skill at plotting. I spoke to him recently, and it is clear that he is doing all the work. Lee is taken up with the television adaptation of Reacher. But they both say that “they” are preserving Reacher so as not to betray his legion of fans. Which, to my way of thinking, would be entirely fair and reasonable. Except for one thing.

Take a look at the cover (already revealed) of the next book. All they had to say was something along the lines of “Lee Child’s Jack Reacher, by Andrew Child”. You could put Lee Child and Jack Reacher in a very large font. That would have been playing it straight. But no. The publishers had to go and shove their “PR bullshit” all over the front cover. The Sentinel is, ostensibly, by “LEE CHILD and Andrew Child”. The fiction begins before you open the book.

There is one remaining mystery. Why did he even let me conduct my mad-scientist experiment on him in the first place, which, contrary to my best intentions, had some “toxic” effect? Was it because, like some ageing boxer, he wanted someone around to record his last big fight? I think it may have been because he was genuinely amazed at his own success and really wanted to know how he did it and needed someone else to do the analysis for him. He also thought that I was a “wild card” and he liked doing things differently. Besides, he used to say, “what’s the worst that could happen?”

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of “Make Me”’ published by Polity

Use promo code: AMP20 for a 30 per cent discount on Reacher Said Nothing and With Child when purchased through politybooks.com

Code valid globally until 30.06.2020

Read more

Lee Child says Tom Cruise is ‘too old’ to star in action films

Past Tense by Lee Child, review: 'I found myself absorbed'

Lee Child gives a master class on writing a short story in 12 hours