The First World War tactic helping Ukraine fight a modern conflict

Every soldier carries an entrenching tool in their battle order. Unwieldy and inefficient, these lightweight folding spades seem designed to strip skin from your palms and the insides of your fingers. Using them is the definition of backbreaking labour. Yet they are almost revered amongst the infantry and kept clean, oiled and sharp, ready for use.

This is because of one very simple truth about trenches: they are the lowest common denominator of warfare. When all of your technology is spent or neutered – and particularly when you are unable to move through, or around, the enemy firepower arranged against you – trench systems will proliferate. Soldiers will dig, because compacted earth is one of the best absorbers of high explosives there is. In a trench you will be completely protected from small arms and, depending on the design of the trench – and except for direct hits – substantially protected from artillery, mortars and air attack. In a well-built trench, you will live to fight another day.

That must be the hope in eastern Ukraine, specifically Bakhmut, where trench warfare has made a reappearance, with artillery and rocket strikes being delivered by both sides over a heavily-mined battlefield. We’ve all seen the horrific reports on the television – of mud, blood, and guts; of soldiers calf deep in liquid mud; of dugouts full of wounded soldiers; of young men and women anxiously awaiting the whine of an incoming shell. On social media, one can also see fields of Russian corpses – the results of the latest human wave of mobiks crashing up against the Ukrainian trench systems. Any ground being taken in Bakhmut, which was visited recently by Zelensky in a morale-building tour, is measured in metres and thousands of casualties – much like it was in the First World War.

But the Russians too are rushing to build trench systems where they expect to defend in the coming months: adverts have appeared on Avito, a Russian version of eBay, seeking craftsmen to help build and fortify trenches in Crimea. The pay rate is 7,000 rubles (£72) a day which, for such risky work, tells you something about the state of Russia’s economy.

For the public, the reports of trench warfare in Ukraine are as surprising as they are distressing. Think back to the aerial wars in Iraq – the high altitude “shock and awe” bombing, that seemed to signal an end to boots on muddy ground. Surely in 2023 we should be fighting hi-tech, low casualty wars using drones and cyber warfare? How is it that we are still stuck in this old way of warfare? The answer lies in those military digs made notorious by poets like Wilfred Owen and Isaac Rosenberg, or in films like All Quiet on the Western Front or Journey’s End: the trenches of the First World War.

Coincident with the first widespread use of high explosive artillery in warfare, both sides were forced into opposing trench systems that stretched from Switzerland to the North Sea. The key word here is forced. Neither side wanted to end up stuck attacking or defending a trench system. But for the first three years of the war, neither side had the ability to manoeuvre around or through their enemies. The movement of the initial stages of the conflict settled into a stalemate from which neither side could escape until the very end of the war.

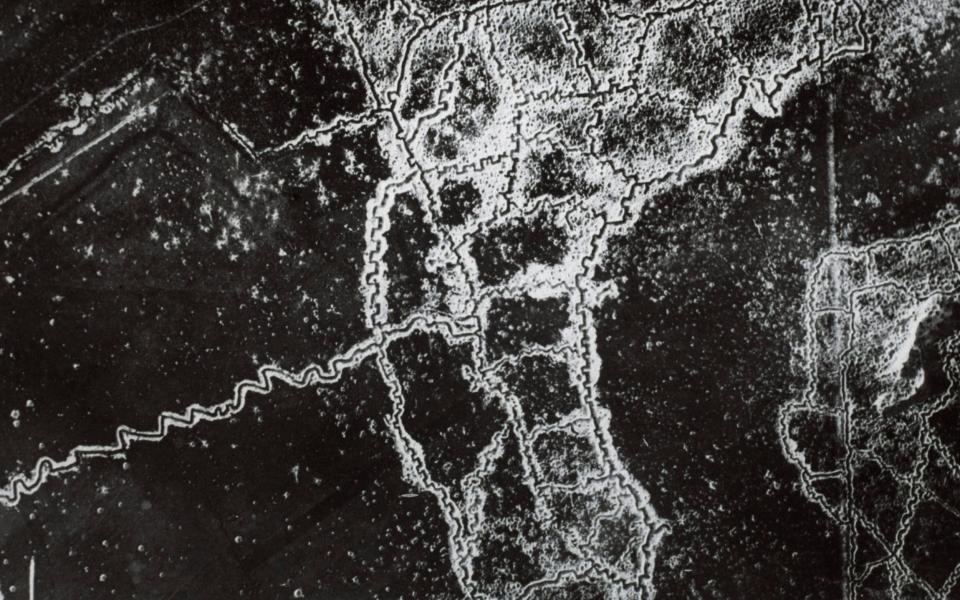

And trenches are as they seem in the films. Uncomfortable and wet. At least eight feet deep so one can move without stooping; a fire step, or series of boxes to stand on, so that the trench can be defended; laid out in zig zags, so that an explosion from a grenade is contained in a short section of trench; reinforced with stakes and planks so that they don’t collapse. And organised into a system, with front line trenches, communications trenches, secondary lines, and bunkers for storage or sleep. And fascinatingly, because they are the lowest common denominator of warfare, they have changed little in design over the past 100 years.

Since the First World War, conflicts have tended to have periods of trench warfare, when both sides are unable, or unwilling to manoeuvre. For example, the different theatres of the Second World War had alternating periods of movement and attrition, dominated by opposing trench systems. Once one side was able to generate a manoeuvre force, the trenches disappeared.

The battle of Stalingrad is a case in point; both sides were locked in gruelling hand-to-hand, building-to-building, trench-to-trench combat before the Soviets were able to drive a force through another part of the line and encircled approximately 250,000 German soldiers in and around the city. This particular encirclement and subsequent surrender of German troops was one of the decisive points of the Second World War and it wouldn’t have occurred had the Soviets not been able to tie up the Germans with trench warfare before striking elsewhere.

The movement at the beginning of the Korean War settled down into trench warfare once neither side could get a movement advantage. They never regained momentum and the armistice line was drawn largely where the trenches were.

And in Vietnam, the Viet Cong built an extensive trench and tunnel system to protect themselves from the overwhelming American bombing, before going on to take Saigon and win the war.

All of these examples demonstrate to us a further simple truth about trenches: you can only win wars with movement, you cannot win by digging in, no matter how elaborate your trench system. Only manoeuvre is decisive, although periods of trench warfare play a key role enabling one side to tie up the other while they prepare an offensive to fall elsewhere.

Hence, the trenches of the Great War so often being described as a stalemate. Neither side had the ability to break through the other’s trench system, so both sides waged bloody – and pointless – offensives against each other. The culmination of the war came in 1918 with the arrival of American troops and allied tanks. Working in combination, they were able to circumvent, or punch through, the German defensive lines. The Germans were forced to sue for peace.

So too in Ukraine, not just in Bakhmut but up and down the front lines stretching from Kherson in the south to Kremina in the north. At the moment, neither side has the ability to break through, or around, the opposing side’s trench systems.

On the Russian side, there are a very large number of mobilised civilians, or mercenaries drawn from Russian prisons, neither of whom have the training, motivation, nor the equipment to break through Ukrainian lines. Russian mobile logistics, too, have been very poor since the start of the war. The Ukrainians, for their part, have a far smaller number of troops but of higher quality, and much higher morale. And so they are relatively evenly matched, and a stalemate ensues.

But 2023 in Ukraine might be like 1918 in France. Since the beginning of this year Western arms have been flowing into Ukraine in ever greater numbers. Specifically, tanks, armoured vehicles, and mobile artillery with greater range than hitherto. Drones to support them. And anti-aircraft missiles to protect them. Ammunition has been stockpiled. Contracts have been issued to provide the second-line logistics and repair; mechanics and drivers have been trained.

Taken together, these capabilities will give Ukraine something like a divisional-sized manoeuvre force – in other words, a few hundred tanks and armoured infantry vehicles. Used carefully, this force could be enough to generate movement somewhere else in Ukraine’s battlefield.

The most obvious place for that offensive is to the south of Zaporizhzhia toward the coast of the Sea of Azov. If successful, this offensive would split the Russian forces in two leaving one group in Crimea and the south, and the other group in the east. Critically, both groups wouldn’t be able to reinforce each other, giving Ukraine even more military options in the future. The most likely time for this offensive? After May, once the Western arms have arrived and the ground has dried out.

Looking at the worldwide political landscape – and specifically the 2024 US presidential elections with the possibility of isolationist, America First candidates – Ukraine knows they need to be successful in this offensive. Not just to make the sacrifice of Bakhmut worthwhile, but to enable them to bring the war to a close whilst they still enjoy overwhelming western support.

Mike Martin is a senior war studies fellow at King’s College London, and author of How to Fight a War