Get the Guru View: Shorter lease tenures, but not short enough

Listing of HDB flats and private apartments on home sharing platforms is not legal, but some homeowners seem willing to take the risk due to the stagnant rental market.

The state has reduced the minimum lease term to three months, rather than the previous six, but continues to outlaw short-term home sharing, citing concerns for the residential character of housing estates. However, homeowners continue to pursue these options, and a few others, to earn a revenue stream from their properties.

By Chang Hui Chew

In several cities, including Singapore, home sharing platforms like Airbnb and HomeAway have faced an uphill battle with regulators, stepping on the toes of hotel operators who are seeing tourist dollars flow to individual homeowners.

In this edition of the Guru View, we examine short term holiday rentals and the continued reason for its persistence despite the heavy penalties against it.

Short-term rentals

Those who place their homes up on short term rental websites continue to do so at great risk. HDB homeowners have seen their flats repossessed by the state if they violated the laws on short-term rentals. Neither are those living in private homes exempt from the law, being liable for up to $250,000 in fines if the authorities were to find them guilty.

It is a positive sign therefore, that the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) recently announced a change to the minimum lease period. Previously, the shortest lease term possible was six months. Under the new revisions, effective 30 June 2017, the minimum lease term has been reduced to three months. This is in response to a rising need for shorter term leases among groups such as visiting academics, exchange students and professionals on work assignments.

The URA however, has emphasised that short-term stays of less than three months through home sharing platforms remain disallowed, and will hold further public consultations on short-term home rentals. The key concern for the authorities seems to be the preservation of the residential character of private housing estates.

This has not stopped homeowners and landlords in Singapore from putting their properties up on home sharing websites. A check on Airbnb for instance, reveals more than 300 listings for full apartment rentals for periods starting from a day and upwards.

The numbers tell us why

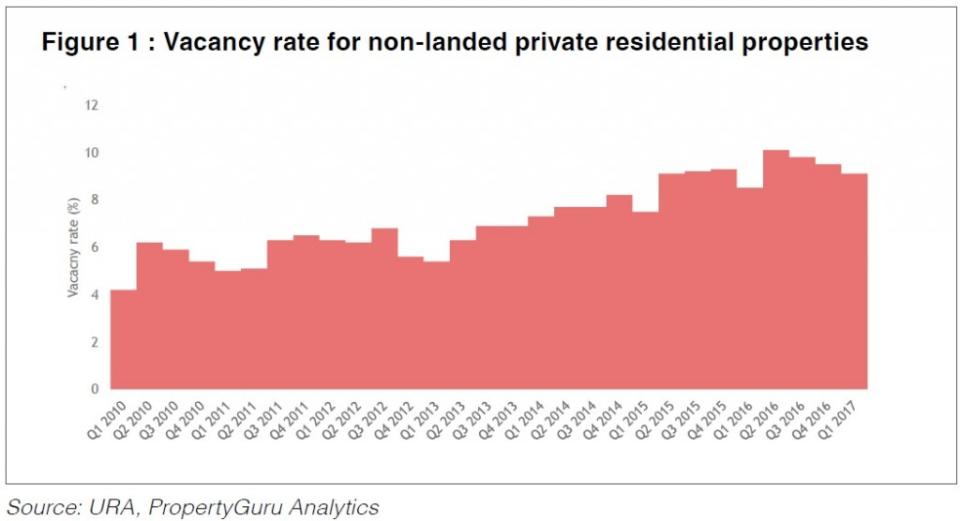

Figure 1 indicates a potential reason why homeowners continue to risk putting up their properties on home sharing sites. The vacancy rates for non-landed private residential properties surged to an all-time high in Q2 2016 with 10.1 percent. Vacancy rates have since improved somewhat, falling to 9.1 percent in Q1 2017. This is however, still higher than the five percent that most market watchers deem a healthy level.

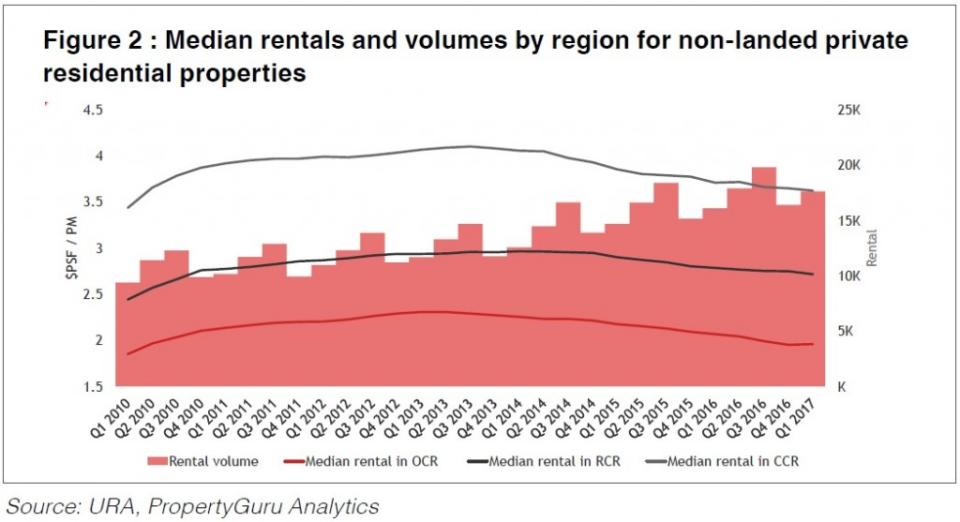

However, landlords are still in trouble. Figure 2 indicates that median rentals have fallen since 2013, and remain flat. Landlords who are relying on rents to support their mortgage payments often find themselves having to top up out of pocket each month. This is exacerbated by the usual maintenance fees and other costs of ownership.

While rental volumes have increased, the relatively high vacancy rates indicate that the overall supply has increased, which has led to more competition amongst landlords. Given this, landlords need other sources of income to support their mortgage payments. It is for this reason that they continue to use alternative sources such as home sharing platforms to monetise their units, and support their mortgage payments.

Let’s take the example of a two bedroom 1000 sq ft apartment in District 9, in the River Valley area. Figure 2 indicates that median rentals in Q1 2017 were $3.62 psf per month. This suggest a monthly rental of about $3,620, assuming the landlord was lucky enough to find a tenant – a chancy thing when expatriates coming to Singapore are dwindling.

In contrast, if the landlord were to lease out the apartment at a rate of $200 per day, for 20 days out of 30 a month, the potential income would be $4,000. For each booking, the landlord can also charge a cleaning fee to cover incidentals as well. The potential revenue could therefore be higher than a regular tenancy.

Going onto a platform like Airbnb allows the landlord a certain degree of flexibility. For instance, when a tenant exits a rental unit, it could potentially take a while before a new tenant can be found. The landlord could continue to try to monetise the unit through such platforms for the short term until they can find a new long term tenant.

Looking at the math, it is rather obvious why landlords continue to risk massive fines to rent out their properties on home sharing platforms.

Preserving residential character

Another common way homeowners monetise their properties is to use it as a place of business. An examination of the guidelines around running home businesses under the HDB’s Home Office Scheme also indicates the authorities’ prioritisation of keeping the residential character of the housing estate.

For instance, businesses that create noise, smoke, dust or high human traffic will not be allowed. Neither are businesses allowed to advertise or place signboards outside of the home to indicate that a business is running there.

Common businesses that can be run out of homes include small group tuition classes, freelance white collar jobs like writing, photography or accounting and so on. However, it is important to note that to keep within the guidelines of the Home Office Scheme, there cannot be more than two non-residents working in the property.

Cat and mouse

Keeping residential spaces clear of noise and chaos is obviously important, else the state would not have placed so much emphasis on it in their regulations. However, this has resulted in the state playing a cat and mouse game with landlords and homeowners as they try to skirt around regulations.

This however, creates a lot of friction, as landlords often feel shortchanged by tightened state policies and a weaker economy that has shrunk the tenant pool and has led them to seek other ways to tenant their units. Furthermore, the state is reliant on surrounding neighbours to report any infractions, which makes enforcement of the current regulations more difficult.

The move to a minimum lease term of three months is indeed a good sign, and shows that the authorities are actively considering the issue. While the state has floated the idea of introducing a different class of residential properties that can be used for short-term rentals, the notion has met with a lukewarm response at best. After all, this would likely increase the costs of the property, while leading to a lot of competition between neighbouring homeowners.

This article was first published in the print version PropertyGuru News & Views. Download PDFs of full print issues or read more stories now! | |||