In Haiti, anger over slum eviction plans

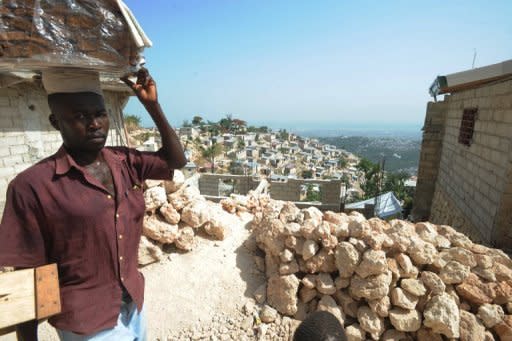

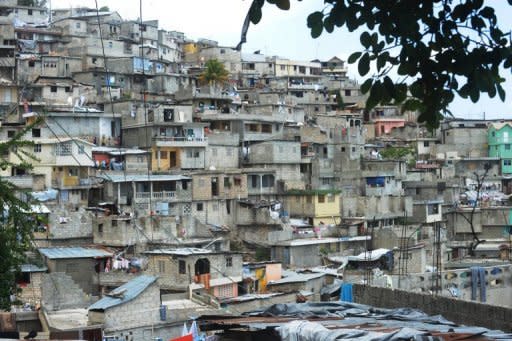

Plans to evict people from slums precariously situated on the vertiginous slopes around the Haitian capital are sparking protests from many who want to stay despite the dangers. Port-au-Prince acts as a magnet in this desperately poor Caribbean nation, which was struck by a catastrophic 2010 earthquake that killed an estimated 225,000 people and displaced 1.5 million, one in six of the population. Haitians flock to the capital from badly deforested and degraded rural areas in the hope of finding work to support their families. But 80 percent of people in the capital live below the poverty line, many in squalid tent cities or in rickety housing near the edge of deadly ravines. Some shantytowns are built on flood plains that risk being washed away when rainstorms come. Many camps lack basic sanitation, leaving them more prone to infectious diseases like the cholera epidemic that has claimed more than 7,500 lives since sweeping the country in the wake of the quake. For all these reasons, there have long been moves afoot to relocate slum dwellers to safer housing. When the quake hit and the international community turned its attention to Haiti's woes, those calls became a clamor. But many slum dwellers don't want to leave. A lot of the housing alternatives being offered are outside the capital, which would mean less opportunity to find work. "I was born here," 62-year-old William Jean told AFP as he sat on a bench facing his small dwelling in the optimistically named "Jalousie" or "Jealousy" neighborhood. "At the beginning, there were just a few houses." In tents or makeshift abodes made out of sheeting, families eke out a miserable existence in the camps. When the flood waters pour in, mothers try to sleep standing up, cradling their babies. "It's a delicate matter," Environment Minister Ronald St-Cyr told AFP, adding "something has to be done." The government recently launched a program promoting the return of earthquake victims to their original neighborhoods, with a subsidy of around $500. St-Cyr has proposed leveling 2,000 houses near the most dangerous ravines. In addition, all new buildings on such sites would be banned. Many slum dwellers are livid at the plans and have taken to the streets of Port-au-Prince to protest, erecting flaming barricades and sometimes clashing with police. "There's no danger in Jalousie," said a clearly angry Sylvestre Veus. "Over my dead body will they evict us." Sylvestre Telfort works for an organization defending the rights of Jalousie residents and has called for a dialogue between residents and the government while encouraging those living in danger to move. "Every socio-economic crisis has pushed people to come here, just like in the other ghettos of Port-au-Prince," Telfort told AFP. Some 400,000 Haitians continue to live in tents, according to the International Organization for Migration. "It's in the shantytowns that they come looking for voters, after that they forget them," said Jocelyn Louis, sitting on his bike. "I say no! No one can tear us away." As those around him muttered their approval, he accused the Haitian government of reacting slowly to the crisis and not respecting "the constitution that guarantees housing for every son of this country." Some residents pointed angrily to luxury homes nearby. "They want to evict us but the owners of two- to three-level houses continue to enjoy their position," said a pregnant woman, pointing to large residences hidden behind high walls with barbed wire. What will happen remains to be seen. Michel Martelly, one of Haiti's best-known musicians with a colorful past as a Carnival singer, was elected president in 2011 promising to end the inequality and corruption and help the plight of the poor. But despite billions of dollars of pledged international aid, progress has been painfully slow.