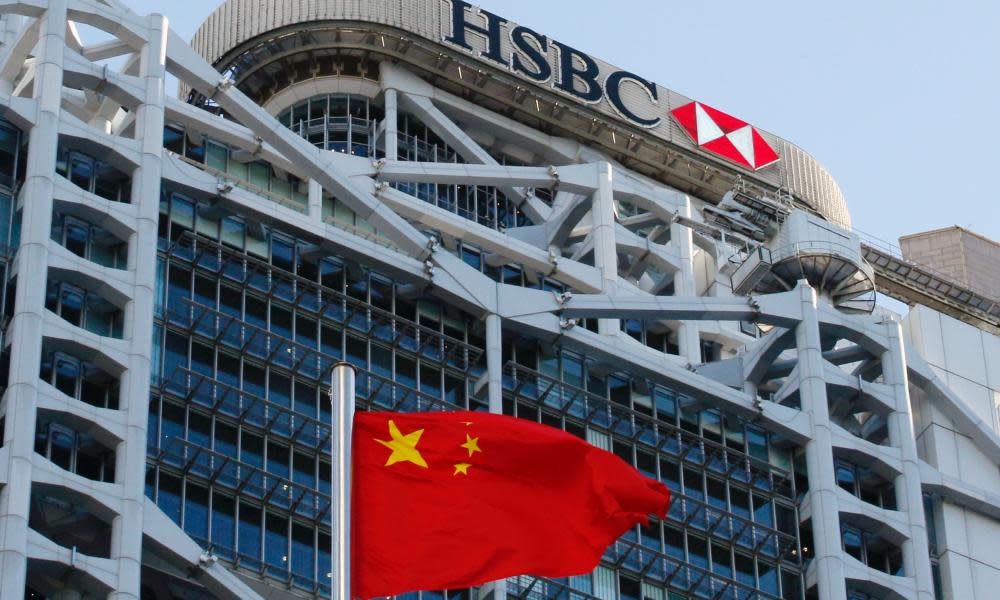

HSBC treads a fine line between angering China and alienating the west

HSBC’s chief executive, Noel Quinn, will be steeling himself for a grilling on Monday, as the bank’s support for China’s controversial security laws in Hong Kong and alleged role in the arrest of a Huawei executive threaten to dominate its second-quarter results.

The company, which has its global headquarters in London but makes the majority of its profits in Hong Kong and China, will be the last major UK bank to publish earnings next week. But while HSBC is likely to report Covid-19 loan loss charges worth $2.7bn (£2bn) – more than the $2.5bn (£1.9bn) it is expected to make in pre-tax profits – the impact of the virus will be one of the easier topics to tackle as the bank juggles competing geopolitical controversies.

Quinn, an HSBC lifer who formally took over as chief executive in March, is likely to choose his words carefully. HSBC has traditionally remained neutral on China, but it was on Quinn’s watch, in early June, that the bank gave its backing for Beijing’s new rules. It said: “We respect and support laws and regulations that will enable Hong Kong to recover and rebuild the economy and, at the same time, maintain the principle of ‘one country, two systems.’” HSBC’s Asia Pacific chief executive, Peter Wong, signed a petition supporting Beijing’s new rules.

The message immediately sparked controversy, with politicians in London and Washington condemning the bank’s support for the anti-democratic laws which, critics said, would undermine Hong Kong’s autonomy under the one country, two systems framework.

Dominic Raab told parliament that Hong Kong citizens' rights 'should not be sacrificed on the altar of bankers' bonuses'

Labour frontbenchers chastised HSBC, saying that the laws it had openly backed violated joint declaration treaty commitments between the UK and China, and limited freedoms for Hong Kong citizens. They also warned that the bank risked being the subject of boycotts similar to those aimed in the 1980s at companies that continued to do business in South Africa during the apartheid era.

The foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, later told parliament that the rights and freedoms of Hong Kong citizens “should not be sacrificed on the altar of bankers’ bonuses”.

In Washington, the House of Representatives passed legislation targeting key Chinese officials, putting banks who do business with Chinese authorities at risk of sanctions. This came weeks after the US secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, called HSBC’s endorsement of the security law a “corporate kowtow”.

Pompeo claimed HSBC’s efforts had been in vain and earned it no respect in Beijing, after China reportedly threatened to punish the bank if the UK blocked technology firm Huawei from involvement in building its 5G network. He warned that HSBC would continue to be used as political leverage by the Chinese Communist party.

The tit-for-tat retaliation between the west and Beijing continues, and HSBC is still caught in the middle, despite remaining tight-lipped. In July, China’s Global Times newspaper – a hawkish state mouthpiece – said China would counter UK moves to suspend an extradition treaty with Hong Kong by targeting companies such as Jaguar Land Rover and HSBC.

Last week, HSBC was forced to rubbish claims by Chinese state media that it had framed Huawei and been an accomplice in US efforts to arrest its chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, in Canada in late 2018. In its statement, posted on the WeChat Chinese social media platform, the bank said it had handed over documents to the US Department of Justice only after it was ordered to do so.

HSBC is now walking a precarious line between offending China – which is its most lucrative market – and losing the support of the UK and other western states.

Few of Quinn’s banking rivals would fancy being in his shoes.