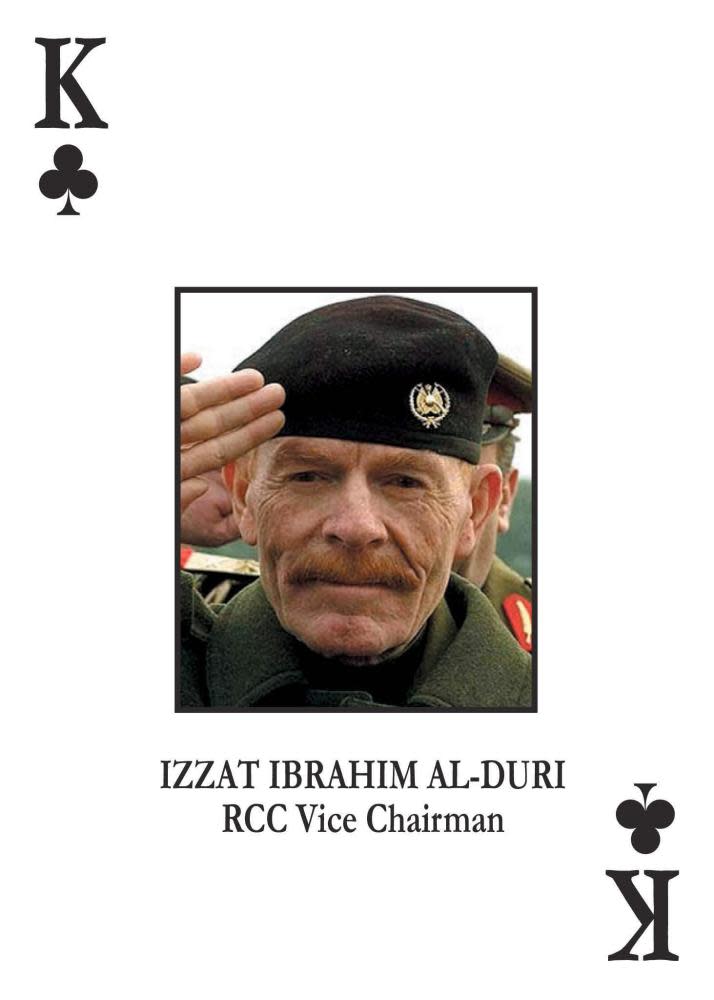

Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri obituary

As vice-chairman of Iraq’s Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) from 1979 until 2003, Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri, whose death at the age of 78 has been announced by the Ba’ath party, ranked second only to Saddam Hussein. The steadfastness he displayed in backing Saddam’s capture of power in 1979 or in crushing Shia and Kurdish revolts in 1991 led to him being regarded at one time as Saddam’s likely successor.

After the US-led routing of Iraq’s power structure in 2003, he survived to lead the remnants of the Ba’ath party, the movement through which Saddam had come to power. In 2014, his fighters helped Islamic State forces to capture the northern cities of Mosul and Tikrit. Isis then relinquished control of a large part of Mosul to Douri’s Naqshbandi army militia, which did not share Isis’s Salafist fundamentalism and so proved more congenial to Mosul’s predominantly mainstream Sunni population. In 2015, it was rumoured that Douri had been killed by Iraqi government soldiers east of Tikrit at the time of the city’s liberation, but the following month the Ba’ath party’s TV station released an audio recording by him referring to contemporary events and distancing himself from Isis. Mosul was liberated from Isis in 2017.

During the 2003 conflict he headed the forces defending the oil-rich north and evaded capture after the fall of Saddam’s regime. Nearly eight months after the Iraq war officially ended, Pentagon sources accused the elusive Douri of working with al-Qaida elements to coordinate a string of lethal bomb attacks against US forces, embassies and aid agencies.

This was familiar territory, for in 1991 he had mercilessly quashed a Kurdish uprising around Kirkuk and Mosul. Douri warned Kurds in early 2003: “If you have forgotten Halabja, we are ready to repeat the operation.” Halabja was the village where 5,000 civilians were gassed to death in 1988. That atrocity formed part of the larger Anfal campaign that between 1986 and 1989 killed at least 80,000 Kurds and razed 4,000 villages. In 1987 Douri signed a directive that sanctioned chemical strikes “to kill the largest number of persons” in designated zones.

Douri was a pale, wizened figure with thinning ginger hair. His familiar grin, Homburg hat and oversized whiskers made him appear almost genial – until he lost his temper. “Shut up, you minion, you traitor, you monkey. I curse your moustache,” he yelled at Kuwait’s delegate to an Islamic summit in Qatar in 2003, a fortnight before the US and its allies launched their second war against Iraq. It would all have been faintly comical but for Douri’s record of purges of political opponents from the time the Ba’ath party took power in Iraq in 1968.

Douri conveyed Saddam’s messages to neighbouring states, an important duty, as the dictator himself never left Iraq after 1991. And it was Douri who negotiated with the Saudis in Jeddah just two days before Iraq illegally annexed Kuwait in 1990. Yet travelling abroad carried perils for him. In September 1999, while undergoing treatment for leukaemia in Vienna, Douri narrowly escaped arrest on war crimes charges by US officials and human rights campaigners.

Saddam’s deputy had only primary school education, yet he benefited from his proven loyalty. “Why should anybody say ‘no’ to Saddam Hussein?” he asked when announcing the results of a presidential referendum of 2002 in which Saddam won 100% of the vote. “He is the symbol of our freedom and of our future.”

Born in Ad Dawr, a village south of Tikrit, he was the son of Ibrahim Khalil al-Douri, a farmer, and his wife, Hamdah Saloum, and in his youth he sold blocks of ice. Tikrit was home to Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, who would become president in 1968, as well as to Saddam, his protege and successor, and many of Iraq’s ruling Sunni junta.

Aggrieved at the injustice, corruption and instability of Iraq in the 1950s, Douri joined the pan-Arab Ba’ath underground as a teenager, befriended Saddam in 1963, and rose swiftly after the 1968 coup, which he helped to plot. He served as agriculture and interior minister, and in 1974 was promoted to the three-man strategic planning committee, after setting up Iraq’s first bacteriological laboratory.

In 1979 came Douri’s key moment. Bakr was forced to retire and Ba’ath ideologues insisted on internal elections to choose his successor. Douri and another Saddam acolyte, Taha Yassin Ramadan, wanted their man sworn in automatically. At a chilling televised Ba’ath Command meeting, Douri forced the RCC secretary, Muhyi al-Mashhadi, to confess his involvement in plotting a Syrian-inspired coup. Mashhadi and four other RCC members were executed by a firing squad consisting of Douri and other colleagues. Douri assumed Mashhadi’s post; by August nearly 500 top Ba’athists had been eliminated.

Douri’s obeisance meant he could never threaten Saddam. In 1998, dissidents lobbed grenades at him when he visited the Shia holy city of Kerbala. Seeking to deflect criticism, he pandered to base sentiments. In late 2002, for instance, he vowed to “liberate Palestine from the claws of the lowly Jews”.

Yet the fearsome enforcer could be charming when required. Douri publicly embraced his former enemy, the Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah, at the 2002 Arab summit in Beirut. Such pictures spoke louder than words to many Arabs. Coupled with growing antipathy to perceived western arrogance, this diplomacy did much to wreck US attempts to “contain” Iraq.

After the collapse of Saddam’s regime, and the deaths of Saddam and his sons Uday and Qusay, many thought that Douri, with a US bounty of $10m on his head (as the King of Clubs in their “most wanted” pack of cards), would not survive for long on the run, especially given his longstanding health problems. But a report in 2005 of his death proved to be false and he emerged as a figurehead of the insurgency, leading the Naqshbandi army.

Douri cannily exploited Sunni anger at being excluded from power and employment by Iraq’s new and increasingly sectarian Shia rulers. Such feelings mounted after the premier, Nouri al-Maliki, broke his pledge to absorb Sunni tribal Anbar Awakening fighters into the military.

Aspects of Douri’s later years mystified observers. Naqshbandi Sufis outside Iraq wondered why their peaceful 12th-century order had been pressed to such warlike ends. Saddam’s former aide Younis al-Ahmed contested Douri’s election as Ba’ath secretary general in late 2006, as many party members felt his professed religiosity contradicted their secularist and nationalist values. Meanwhile military analysts questioned why his army, which led a coalition of Sunni militias, would ally with Isis. After all, Isis’s predecessor, al-Qaida in Iraq, had often clashed with Douri’s fighters, and Isis habitually demolished “heathen” Sufi shrines.

In fact Douri showed consistency in pursuing Ba’athist objectives. In 1993 he had spearheaded Saddam’s opportunistic “return to faith” campaign. Nor did his antipathy wane towards Iraq’s Shia majority, whom he said took orders from Iran. In 2013 he appeared in an internet video calling for the overthrow of Maliki’s “Persian” government. Douri, who allegedly grew rich on pre-2003 oil smuggling deals, was credited with funding the Isis surge of 2014. “The liberation of Baghdad is around the corner,” he proclaimed. By 2015, however, his gamble seemed to backfire as jihadists squeezed his cadres out of one place after another. In his last video, aired in April this year, he blamed Iraq’s present rulers for the deaths of millions and demanded a “popular revolt against traitors”.

He married in 1968 and is said to have had other wives. One of his daughters was briefly married to Uday Hussein, a son was reportedly killed in Tikrit in 2014, and several other children survive him.

• Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri, politician and military leader, born 1 July 1942; died 26 October 2020