Japan and Germany: A contrast in coming to terms with horrors of war

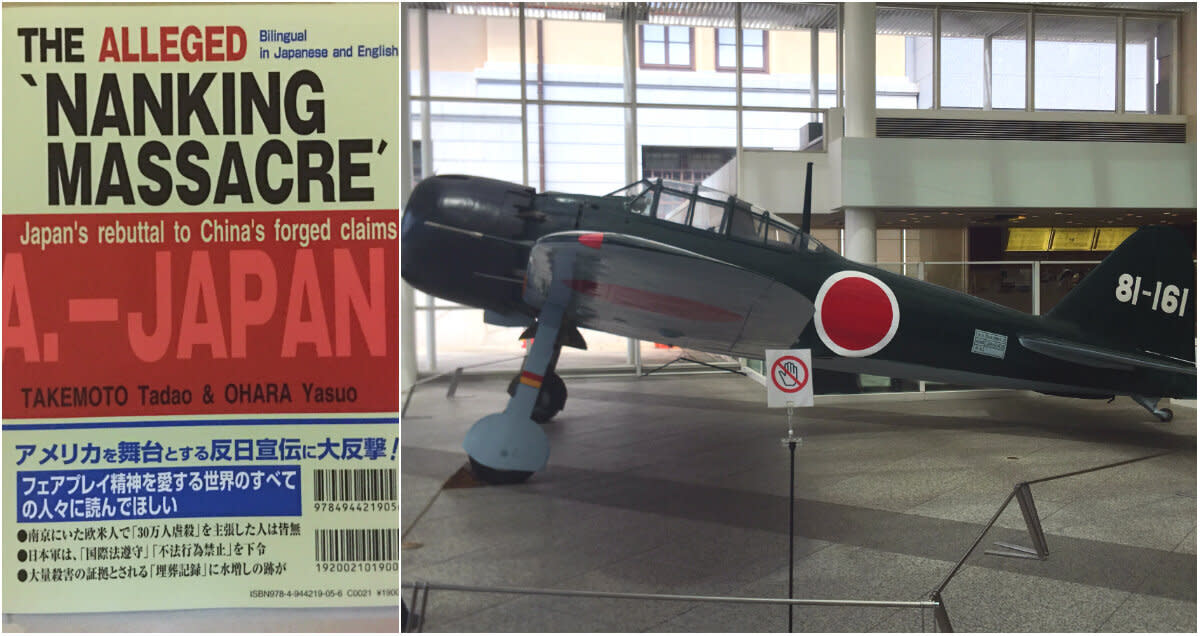

TOKYO — At a gift shop in the Yushukan War Museum in Tokyo, a bilingual book bears a striking title that would capture the attention of anyone with an interest in modern Japanese history.

“The Alleged ‘Nanking Massacre’ - Japan’s rebuttal to China’s forged claims” by Takemoto Tadao and Ohara Yasuo, written in Japanese and English, aims to debunk what the university academics consider as myths perpetuated by the Chinese about the highly incendiary issue.

The academics reject the generally accepted estimate by historians that around 300,000 Chinese were massacred in the days leading to and following the Japanese army’s invasion of the then capital of China in December 1937. They cited reasons such as lack of reliable eyewitness accounts and allegedly doctored photographs of war crimes committed by Japanese soldiers.

The Museum is located within what many Japanese consider as hallowed grounds for their war dead: the Yasukuni Shrine. But for the victims of Japan’s wartime aggression and colonialism in Asia, such as China and South Korea, Yasukuni typifies the country’s inability to come to terms with its barbaric acts of murder, pillage and rape across the region during the years of unrelenting warfare from the 1930s until 1945. Yasukuni has been a recurring source of diplomatic friction between Japan and its Asian neighbours over the decades, particularly when top Japanese ministers paid their respects to the 2.5 million people enshrined at the site including 14 Class A war criminals.

Visitors who enter the Museum entrance would be greeted by an A6M Zero fighter aircraft, the variants of which were in action during World War II including the attack on the American Navy at Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941. Two war relics on display epitomise the maniacal zeal of the Japanese to die for the nation and Emperor Hirohito through suicide missions towards the end of WWII: a replica of the Yokosuka MXY-7 Okha (cherry blossom) kamikaze attack aircraft and the “Shin-yo” Model I kamikaze attack boat.

Whitewashing of Japanese wartime history

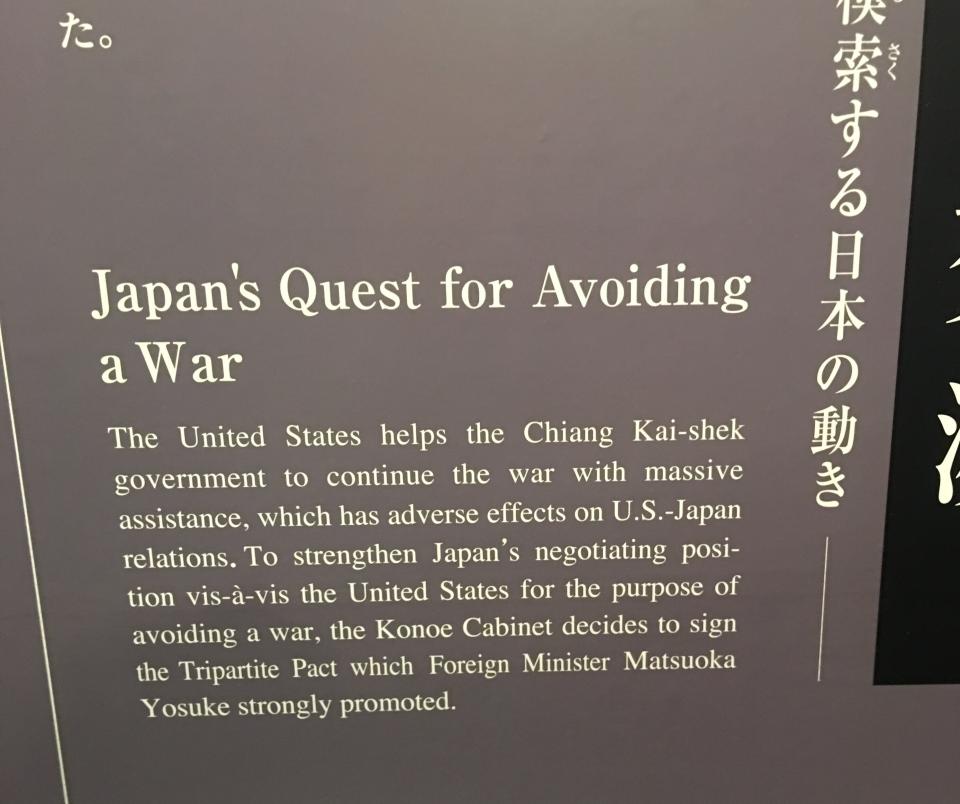

On the second floor, panels written in Japanese and English explain the geopolitical circumstances propelling Japan towards its involvement in the different wars. To discerning readers, the panels were an exercise in the whitewashing of Japanese wartime history.

One panel on the infamous Marco Polo Bridge Incident on 7 July 1937, which sparked the Second Sino-Japanese War, refers to the hostilities as “The China Incident Campaigns” as neither side had declared war against the other. Some historians have said that the Japanese exploited a skirmish at the Bridge as a pretext to trigger a wider war against China. The panel does not assign blame on any side and instead notes that “the Japanese government abandoned its efforts to prevent incidents from escalating”.

During this writer’s visit to the Museum in April this year, he met an American visitor who was shaking his head in disbelief while reading several panels. The American was reading about the trade embargo on key resources imposed by the US and its allies against Japan prior to the Pearl Harbour attack. A panel explains that given the economic situation, “Japan’s survival hinged on locating a new supplier of resources”. Another panel outlines the Japanese commitment to avoid a war through diplomatic negotiations with the Americans.

The explanations for the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War and WWII at the Museum were as disturbing as the attempt to gloss over the atrocities committed by the Japanese. This writer did not come across a single photo of Chinese or other Asian war victims, and instead saw numerous photos of heroic Japanese soldiers, pilots and naval personnel who died in the “defence” of their homeland.

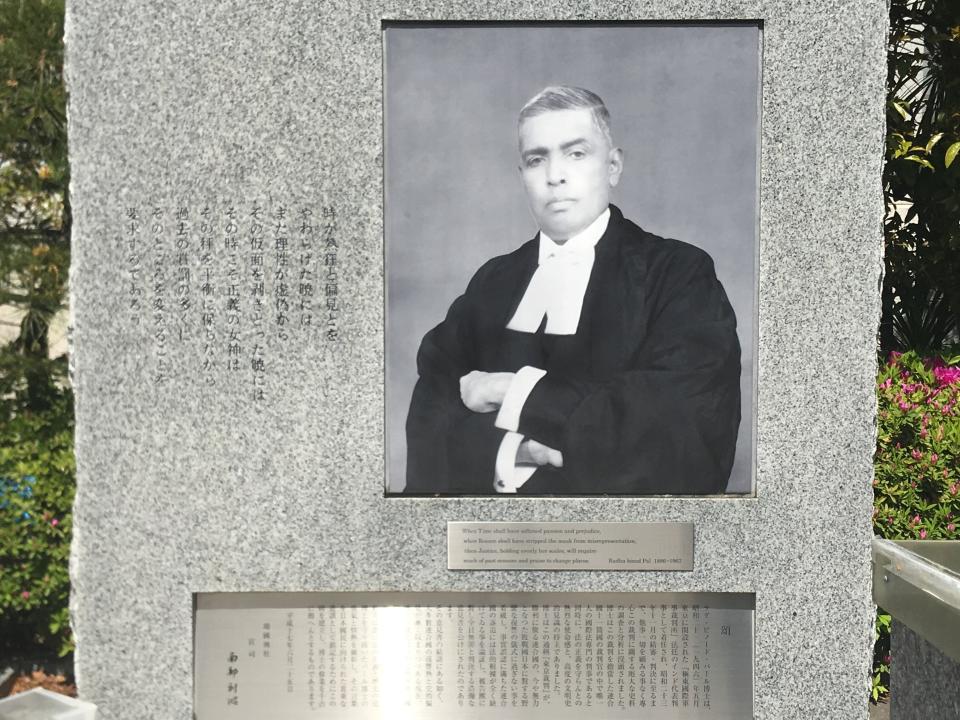

Outside the Museum, a monument in honour of Indian judge Radhabinod Pal underscores the lack of remorse among conservative Japanese politicians and intellectuals about their country’s wartime history. Pal was the sole tribunal judge at the Tokyo war crime trials who wrote a judgement in 1948 to state that the Japanese defendants, including Class A war criminals, were not guilty. In his book “Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan” by Herbert Bix, the American historian wrote, “Whenever Pal appeared in court, he unfailingly bowed to the defendants, whom he regarded as men who had initiated the liberation of Asia.”

Many Japanese people are unaware about the horrors of war inflicted by their forefathers, in a country where schoolchildren are taught a sanitised version of their modern history. In his book “To America: Personal Reflections of an Historian”, Stephen Ambrose wrote, "The Japanese presentation of the war to its children runs something like this: 'One day, for no reason we ever understood, the Americans started dropping atomic bombs on us.’”

Acts of repentance by Germany

Casual visitors who walk around a nondescript residential area in central Berlin, near the former government district at Wilhelmstrasse, might not pay much attention to the beige-coloured buildings capped with red rooftops. It is only when they come across a notice board that they would realise that one of the most notorious dictators in history died in the area more than seven decades ago.

The notice board notes that on 30 April 1945, Nazi Germany’s leader Adolf Hitler committed suicide in his Berlin Bunker. His body was then burnt on the open ground of the then New Reich Chancellery, somewhere around the car park of the residential area.

Postwar German authorities were determined to ensure that Hitler’s last vestiges of power were demolished to deny Nazi sympathisers a chance to pay homage to the dictator, whose armed forces was responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of people and destruction of cities across Europe and North Africa during WWII.

The acts of contrition expressed by successive German governments were evident in the meticulous curation of various Nazi- and WWII-related sites in cities like Berlin and Munich to remind visitors of the horrors of Hitler’s regime.

One of the best sites is the “Topography of Terror” in Berlin, an exhibition that highlights the Nazi security organs responsible for the organisation and perpetration of terror across Europe. It is located in the same vicinity of the headquarters of the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police, and the offices of two top Nazi leaders: Heinrich Himmler, one of Hitler’s most trusted lieutenants, and Reinhard Heydrich, who was a key planner of the Holocaust in Europe.

In the decades following the war, Germany undertook highly symbolic measures to show its penitence towards the Jewish communities around the world. It built the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, which is a large site of over 2,000 concrete slabs near the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, to commemorate the millions of Jews who died during the Holocaust. Many synagogues today across Germany come under regular police protection.

Remembering resistance fighters and victims of Nazism

Perhaps the most poignant reminder of the heinous murders carried out by Nazi Germany is the Dachau concentration camp, located near Munich. The first of its kind to be built in Germany in 1933, Dachau became a blueprint for similar structures of mass extermination in the country and across Europe. The crematorium that was used to kill Jews and thousands of other prisoners has been preserved. During this writer’s visit to Dachau in 2013, he saw a teacher who was briefing a group of German school children about the history of the site.

Not only does modern-day Germany prominently publicises the Nazi institutions and instruments of terror, it also honours the German heroes who died while valiantly fighting to overthrow Hitler’s regime.

In the University of Munich, there is a memorial to the anti-Nazi group White Rose, in the form of scattered leaflets replicated on ceramic tiles at the entrance. The group’s most famous members were Sophie Scholl and her older brother Hans Scholl, both students of the university. They were caught distributing anti-Nazi leaflets at the university in 1943 and later sentenced by a pliant Nazi court to be beheaded by guillotine.

At the historic Bendlerblock in Berlin, the Memorial to the German Resistance marks the spot where Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg and other officers who plotted to assassinate Hitler were executed.

As the two strongest members of the Axis Powers that triggered WWII, Japan and Germany were responsible for causing the majority of the total estimated deaths of more than 70 million people during the war. As such, the extent to which they recognised their horrific war crimes after 1945 were a matter of global interest and a measure of their repentance.

German Chancellor Merkel advised Japan

Germany has earned considerable goodwill from the global community for confronting its dark history during the Nazi era. In contrast, Japan is still viewed with distrust by some of its Asian neighbours for failing to adequately admit to its wartime crimes and a propensity to express guilt in vague terms.

In August 2015, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe did not issue a new apology to the country’s wartime victims in his statement to mark the 70th anniversary of the surrender of Japan. Expressing “deepest remorse” and “sincere condolences”, he said, “We must not let our children, grandchildren, and even further generations to come, who have nothing to do with the war, be predestined to apologise.” His comments prompted rebukes from China and South Korea, with the Xinhua news agency slamming Abe for his “linguistic tricks”.

A similar issue flared up in February this year after a South Korean lawmaker asked then Emperor Akihito to apologise over “comfort women” who were forced to provide sex for Japanese soldiers before and during WWII. Abe said the Japanese people were angered by the lawmaker’s comments while Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Kono demanded an apology from Seoul.

When German Chancellor Angela Merkel visited Tokyo in March 2015, she reminded Japan to confront its wartime past and seek better ties with South Korea by citing her country’s postwar reconciliation efforts with France. Merkel said that Germany has “faced its past squarely” and “there was the acceptance in Germany to call things by their name.”

Her remarks drew praise from government officials and the media in South Korea and China. Hong Lei, a spokesman for China's Foreign Affairs Ministry, said, "Japan should have sincerity (like Germany), rather than ignore history.”

The response to Merkel’s remarks by Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida further highlighted why similar European fence-mending over WWII history remains elusive between Japan and its neighbours to this day. Calling it inappropriate to compare the postwar settlement efforts by Japan and Germany, Kishida said, "The background, what happened to Japan and Germany during the war and what countries their neighbours are, is different.”

All eyes are now on newly crowned Japanese Emperor Naruhito when he makes his first public statement on WWII. In 2015, then Crown Prince Naruhito spoke about the need for Japan to view its wartime past “correctly”, in veiled comments widely seen as directed at Abe and his revisionist supporters. Despite the limitations of postwar imperial law, Naruhito could be the best hope to jolt his country out of its inertia to unequivocally deal with the darkest chapter of its history.

Related story

COMMENT: Should the ashes of Japanese war criminals in Singapore cemetery be removed?