Japan GDP shake-up knocking world's growth indicator

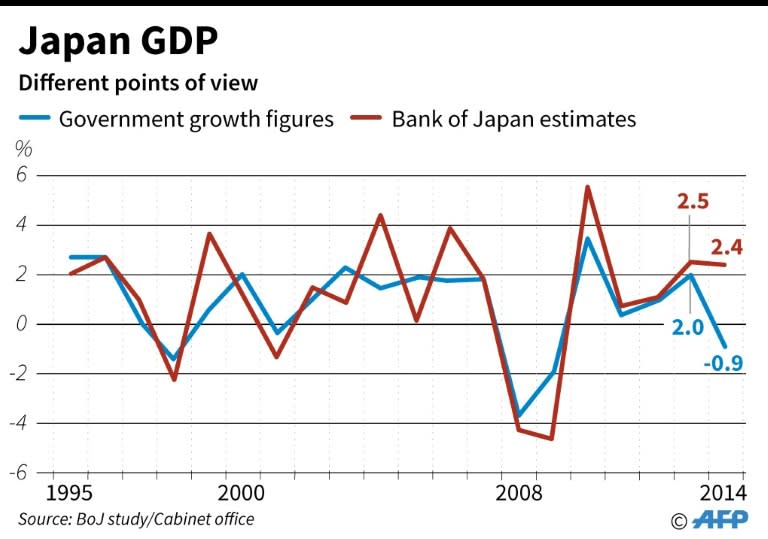

Japan is eyeing an overhaul of how it measures growth in its economy, and that is stirring fresh questions about the reliability of the world's go-to indicator - gross domestic product -- in the digital age. Researchers at Japan's central bank crunched some numbers recently and concluded that the booming-economy-turned-perennial-laggard actually grew 2.4 percent in fiscal 2014 rather than shrinking an official 0.9 percent. If those numbers are correct, it might mean a recession that year never happened. Tokyo's review could have broader implications as other countries also question a measurement that was born out of the US Great Depression. "The Bank of Japan study is just the latest in a series of new questions raised about official GDP numbers," Erik Nielsen, chief economist at UniCredit Research, said in a commentary. "If we are flying blind, then how can we expect good policymaking?" Whether it's the steel produced to make your car, that tomato from the supermarket, or your last dentist appointment, GDP adds up the value of goods and services in an economy over a certain period -- offering a snapshot of a country's productivity. In the old days, you might have booked a trip to Paris through a travel agent, bought a map to get yourself around the city and called the kids back home with a calling card. All those purchases go towards GDP. Nowadays, many consumers turn to online booking apps such as Expedia and Airbnb, tap on free-to-use online maps, and phone home through no-cost sites like Skype or WhatsApp -- and it's not easily accounted for. “All that economic activity that used to be in GDP is now being generated by services that are either free or are paid for by advertising rather than the consumer," Professor Charles Bean, a former deputy governor at the Bank of England, said in a recent video. - 'Never been harder' - Bean, tapped by London to study the problem, concluded in a report this year that Britain's economic activity is being understated. "Ironically, GDP may actually fall even though the quantity and quality if services is increasing," he said. "Measuring the economy has never been harder.” Luxembourg-based EU statistics agency Eurostat has revised the way it measured GDP to get in line with recommendations from the United Nations Statistical Commission. According to the Bruegel think-tank in Brussels, the impact on base GDP numbers from the change in methodology varied hugely across the EU, from 0.3 percentage points in Luxembourg to 9.3 percentage points in Cyprus. Many EU countries also introduced new sources of GDP and updated methods, including a new, EU-wide way of measuring illegal or underground activities such as the drug trade and prostitution. Other countries face different measurement challenges. With inflation running at an estimated 475 percent annually, Venezuela's central bank has stopped publishing key economic data on a regular basis, while China, the world's number two economy, has been accused of tweaking its numbers -- in both directions. "The Chinese government likes to make the GDP trend to look smoother than it really is," said Claire Huang, a Societe Generale China economist based in Hong Kong. "It's not always making it higher...It actually lowered it when the economy was growing very fast back in 2010. It wants to downplay the level of fluctuations in its economy." For Japan, the possible culprits behind any mis-measurement include fewer companies and households filling out offical surveys -- the BoJ used tax returns instead -- and missing out on big chunks of the internet economy. - 'One-off corrections' - Officially, Japan posted 0.2 percent growth in April-June. "A measurement mistake of 0.5 percent in today's Japan... easily pushes the economy into measured recession or pulls it into acceptable growth," said Martin Schulz, an economist at Fujitsu Research Institute in Tokyo. But a few corrections don't mean Japan's once red-hot economy is back on top. "Most of the corrections will only lead to one-off corrections and not to an undiscovered growth trend," Schulz said. Despite attempts to challenge its prominence -- Himalayan kingdom Bhutan relies on a Gross National Happiness index -- GDP still has a huge impact on policymaking. "If GDP is higher (than thought), then productivity is not quite the problem we thought it was," said Nielsen from UniCredit. Dirk Philipsen, an economic history professor at Duke University in the United States, has big doubts about GDP. "The question is what do we mean by growth and if we define it by GDP, is it long-term sustainable? "The answer is most likely 'No'. It requires too much destruction of the ecosystem." Even modest GDP increases don't necessarily mean much for those struggling to get by -- and they're turning to the likes of US presidential candidate Donald Trump or far-right French politician Marine Le Pen for answers, Philipsen said. "A large number of people realise, or at least sense, that their daily experiences are not reflected in the current metrics," he said. "GDP is going up but their life is not getting better."