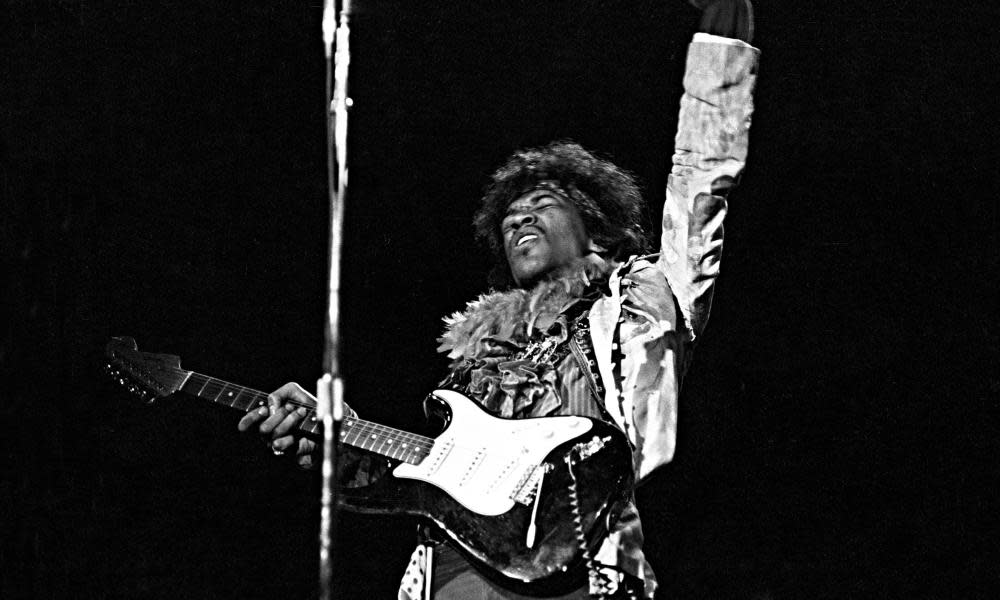

Jimi Hendrix, Monterey Pop 1967: a live performance never bettered

When, in June 1967, Brian Jones sauntered onstage at the Monterey Pop Festival to introduce Jimi Hendrix as “the most exciting guitar player I’ve ever heard”, the Rolling Stone got a bigger reception than the act he was announcing. Although a fair few of the 90,000 in attendance that final evening would have heard Hendrix’s British hits on America’s new-fangled FM radio, this was effectively the guitarist’s homeland debut. Indeed, the Jimi Hendrix Experience only made it on to the bill after strong lobbying from Paul McCartney, a member of the festival’s organising committee (alongside Mick Jagger, Brian Wilson and Smokey Robinson). That Derek Taylor, formerly the Beatles’ press officer, was one of Monterey’s three founders (the others were Mamas and Papas’ John Phillips and record producer Lou Adler) and knew all about the trio, secured them a prestigious Sunday evening slot.

Coming on after 40 minutes of genial musicality from the Grateful Dead, the Jimi Hendrix Experience had maximum impact as they blasted into their high-octane take on Howlin’ Wolf’s Killing Floor followed by Foxy Lady, the latter introduced with a self-assured: “Dig this.” Their first big American gig might have been a touch belated, but as a band they were more than ready after honing their stuff on the European psychedelic scene. Mitch Mitchell’s jazz-rooted drumming was not phased by the guitarist’s flights of fancy and able to take a few excursions of its own while holding the groove. Noel Redding’s liquid playing approached the bass as another lead instrument, contributing ideas of its own rather than simply supporting. The threesome meshed superbly on what is acknowledged as one of the best festival sound systems ever – play their Live at Monterey album and you’ll have to remind yourself there are only three people on stage.

Central to this, of course, is Hendrix himself: his dazzling technique combines with a use of feedback and fuzz to almost casually create music of stunning strength and inventiveness. His vocals are warm, wistful or lascivious on cue, and never less than engaging; what passes for banter between numbers is winningly self-effacing. This is peak Hendrixosity, a live performance that has probably never been bettered or was never recorded if it was.

The finale of a properly wild version of Wild Thing was the big talking point – unconventional guitar-playing, humping PA equipment, rolling around on the floor and the sacrificial-type guitar burning. But some 50 years later, this looks contrived – merely tricks that obstruct the real magic. The true high point comes midway through, with the run of Hey Joe, Can You See Me and The Wind Cries Mary. Away from the gimmicks, these 12 minutes establish Hendrix as the embodiment of the counter-culture’s musical revolution.

The blues was squarely at the centre of so much new rock music. Here was a player who, unusually in that world, saw the blues as a living entity, not a museum piece to be reproduced. With this performance Hendrix let it be known he understood the blues as a spirit rather than a defined expression and presented its power retooled in a way that musically made sense to hippies’ forward-facing ideologies. Importantly, for the generation that was vociferously protesting the war in Vietnam, the Jimi Hendrix Experience reeked of danger, while the debauched dandy apparel and afros from both the black and the white guys was about as far from wholesome as possible. All of this made a big contribution to funk as it was beginning to take shape, as Hendrix reclaiming the blues became one of the crucial bridges between the Black Arts Movement of the early 1960s and funk as a renaissance emerging at the end of the decade.

Related: 'It felt like a wonderful dream' – DA Pennebaker on making Monterey Pop

Monterey Pop wasn’t the first or the most famous rock festival but it was the most significant, marking the moment the previously regional hippy scenes came together and, culturally, could build. Jann Wenner, an attendee who a few months later would launch Rolling Stone magazine, summed it up: “Monterey was the nexus – it sprang from what the Beatles began, and from it sprang what followed.” The festival’s success and exposure turned the US music business upside down by bringing the underground overground with more than a glint of gold about it: “rock”, as opposed to pop or rock’n’roll, became recognised as the new cash cow and executives started conspicuously growing sideburns.

Ultimately, the Monterey Pop Festival belonged to Hendrix. He arrived as a relative unknown to become the personification of organiser John Phillips’ intentions for three days of inclusivity and adventure during the Summer of Love. It is a bitter irony that Phillips had scheduled his group, the Mamas and the Papas, to close the weekend – ie to go on right after Hendrix. Their gentle psychedelic pop looked decidedly anachronistic: there could be no doubt that rock’s baton had been passed forward.