K. Rouge cadres have little appetite for landmark trial

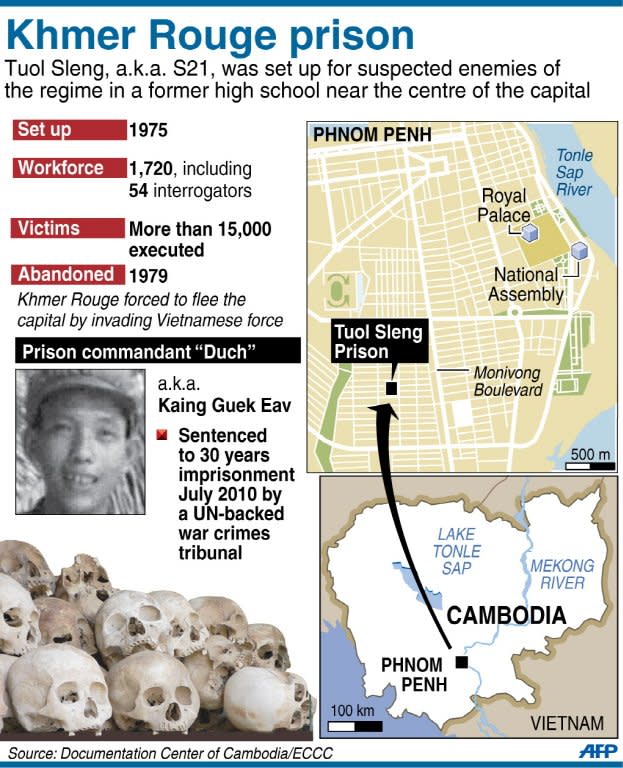

It has been hailed as a chance to heal a traumatised nation, but former foot soldiers of the brutal Khmer Rouge say Cambodia's genocide trial is a waste of money that will only re-open old wounds. The landmark case against the most senior surviving leaders of the hardline communist regime, which began in 2011, has been described as one of the world's most complex in decades and is costing tens of millions of dollars. The tribunal, set up in 2006 after long negotiations between Cambodia and the United Nations, was billed as an opportunity to find justice and reconciliation after one of the worst horrors of the 20th century. But in former Khmer Rouge strongholds along the Cambodian-Thai border, ageing former regime cadres would rather that the bloody episodes of the late 1970s are forgotten. "The wounds are almost healed, but I think the trial is like a sharp stick piercing the old wounds," said Nhem Preuong, who joined the Khmer Rouge as a soldier in 1973. "Everyone suffered under the regime, but we should let hatred go," said the 58-year-old father of three, who is now a local councilor and married to another former Khmer Rouge cadre. "We should bury the past." Led by Pol Pot, who died in 1998, the Khmer Rouge wiped out up to two million people -- nearly a quarter of the population -- through starvation, overwork or execution in a bid to create an agrarian utopia. The northwestern region of Malai, close to the border with Thailand, is home to thousands of former Khmer Rouge members, some of whom fill local government positions, while others sell goods at a dusty local market. The town was the powerbase of former Khmer Rouge foreign minister Ieng Sary, who died on March 14 at the age of 87 while on trial for war crimes and genocide over his role in the regime's 1975-1979 reign of terror. About 1,000 mourners attended the funeral of the regime co-founder, highlighting the divide between supporters and victims of the regime. Fellow ex-cadres are fearful of further arrests, said Phy Phuon, 66, who worked as Pol Pot's bodyguard and later at the regime's foreign ministry. "If they arrest more Khmer Rouge, it will break the nation as a whole. Some Khmer Rouge are not happy with the trial," said Phy Phuon, a former deputy governor of Malai, where he estimates more than 10,000 former cadres now live. The ex-Khmer Rouge have not been reintegrated into Cambodian society, according to Youk Chhang of the Documentation Centre of Cambodia, which researches regime atrocities. "Without... education, they will continue to deny the crimes were committed by the Khmer Rouge. Reconciliation would then be uncertain and Cambodia would remain a broken society," he said. Many cadres joined after their former king Norodom Sihanouk, then exiled in China, aligned himself with the Khmer Rouge in 1970 and urged Cambodians to join a guerrilla war against a regime that took power after a US-backed coup. So far the UN-backed court -- which has been dogged by allegations of political meddling and frequent funding problems -- has spent more $170 million. It has achieved just one conviction, sentencing former prison chief Kaing Guek Eav, known as Duch, to life in jail for overseeing the deaths of some 15,000 people. Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, himself a former cadre, is strongly opposed to further trials beyond the current cases, saying they could destabilise the country. The court suffered a major blow in mid-March with the death of Ieng Sary, who escaped court judgement for his alleged role in the atrocities. His death left two defendants on trial -- "Brother Number Two" Nuon Chea, 86, and former head of state Khieu Samphan, 81, who both deny charges of war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity. "They're just wasting money for nothing," said former regime fighter Lon Roan. "They set up the court many years ago, but I see no results so far. Why should there be a trial when these old people are waiting for their deaths to come?" said the frail 78-year-old. While survivors of the "Killing Fields" era are anxious to see justice, it is also unclear how significant the trial is for the wider population, with 70 percent of Cambodians under the age of 30. Tribunal supporters such as Youk Chhang, however, hope the process will force even former Khmer Rouge fighters to look back at their bloody history. "The court forces them to face the past -- their past," he said. "It is difficult for them but it is a process for a better future for all including themselves."