"A life devoted to nursing, despite the discrimination I've experienced"

During Black History Month - and always, for that matter - it's important that we take time to reflect on the stories of members of the Black community, and celebrate the vast contributions the community has made. In this piece, we hear from Professor Dame Elizabeth Anionwu, a trailblazing NHS nurse with a career spanning over five decades.

This year has been a stark reminder of the importance of one of Britain’s greatest treasures, the NHS. During a pandemic with no current vaccine, that affects Black people in higher numbers, it’s the NHS workers, doctors and nurses, risking their lives even in the face of adversity, who are the real heroes.

Nurses and midwives make up the largest proportion of professional workers in the NHS in England and the NHS is the biggest employer of Black and ethnic minority people. The history of Black nurses and medical workers in the UK stretches far back, even before the NHS existed. From Mary Seacole, a British-Jamaican nurse who worked through the Crimean War in the 1800s to the Caribbean people who travelled to England to work for the NHS in the 1940s, Black nurses have been an important thread in the tapestry of this country’s history.

The NHS is made up of incredible Black people who have been pioneers in their fields, people like Professor Dame Elizabeth Anionwu. With a career spanning over five decades, Anionwu was the first UK nurse to specialise in caring for patients with sickle cell and thalassaemia, an inherited condition that especially affects people from an African and Caribbean background. Elizabeth helped to set up the Mary Seacole Centre for Nursing Practice at the University of West London, where she is the Emeritus Professor of Nursing. She’s also a fellow at the Royal College of Nursing. It’s clear she is fervently passionate about caregiving and improving the wellbeing of not just patients, but the Black nurses following in her footsteps.

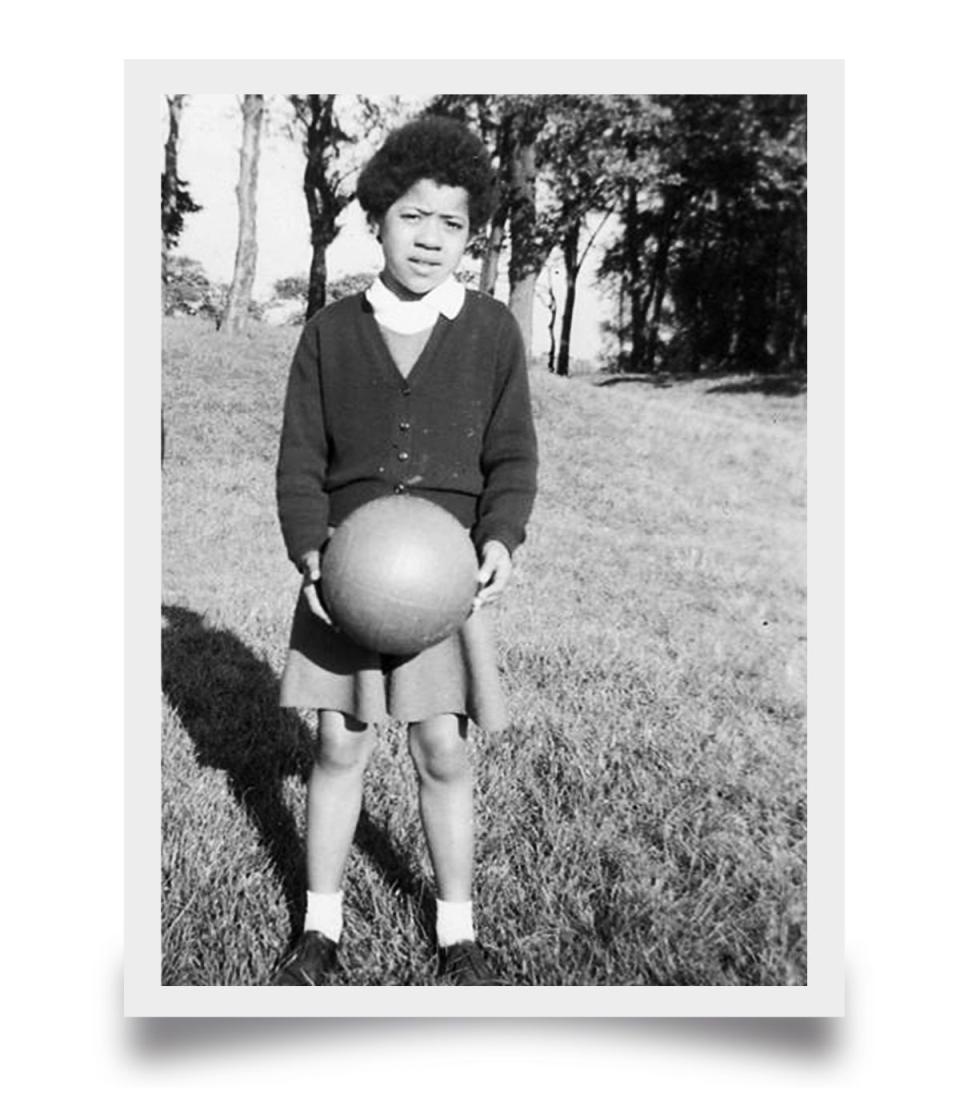

While so much has changed since she became a nurse after leaving school at age 16 in the early 1960s, the challenges Elizabeth faced at the start of her career echo those of Black nurses in the UK today. We caught up over video call, to talk about how she got into nursing, her experiences in the profession, and what it’s like for Black NHS nurses working now.

Elizabeth lived in a children’s home until the age of nine and it was actually having eczema and one friendly nun which led her on the journey to becoming a nurse. “In my mind, I called her the white nun. All the nuns were white, but she wore a white habit,” Elizabeth says. The nun would use distraction therapy to help remove Elizabeth’s painful bandages.

“She used what I thought were quite naughty words, like ‘bottom’. And I would burst out laughing... I really loved that woman,” Elizabeth remembers. “Just before I left the convent, I think I left at the age of nine, I discovered something called a nurse.”

Growing up Black in Britain in the '40s and '50s was a challenge. In the children’s home, where she was the only Black child, Elizabeth repeatedly washed her face, aggravating her sensitive skin in the process, in the hope of becoming white. “I don't think I told anybody,” she remembers

Although Elizabeth was born and raised in the UK, she still had to bear the brunt of being othered and made to feel different because of her race, often being asked the “Where are you from?” question, many Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic people are burdened with to justify why they are in this country. Birmingham wouldn’t suffice as an answer, it seemed, which led to Elizabeth feeling anger and frustration.

“I've been sitting with anger, and I still am sitting with anger in my belly,” she says honestly. But Elizabeth doesn’t see this emotion as something to hide from, rather a driving force for change. “Anger is good”, she says. “If you use the energy of anger, positively.”

At 16, Elizabeth became a school nurse assistant and then started her nurse education course in 1965 in Paddington General Hospital.

Elizabeth recalls a point at the start of her career, in the early ‘70s, when she almost failed as a trainee health visitor. “I dared to question the illogical use of the way they were collecting what we've called ethnic monitoring data,” she remembers. The data was for funding for marginalised groups like refugees, but Elizabeth questioned health visitors who had no interpreters for non-English speaking patients. Some were collecting the statistics based on patients having “odd” names, or not being able to speak English. “The manager failed me on my practical placement,” Elizabeth says.

She stood by her beliefs and was political, constantly questioning, debating and even going to conferences about the NHS. Eventually, Elizabeth contested, an investigation was opened, and she passed the training. “Those are some of the memories I've got of why it was so helpful to be political. I think it just sharpened my attitude to areas of injustice, particularly racism.”

It wasn’t until she became a health visitor in Brent, London and met one special family who had a son with sickle cell, that she became the UK’s first specialist nurse in the care of patients with sickle cell and thalassaemia. “The mother was distraught,” she says, “she just wanted more information, and I realised at that time I had never had a lecture on sickle cell anaemia in my nurse training.” Later in her life, Elizabeth found out her cousin also had sickle cell. “It was personal”, she says. “It made me feel very angry and very concerned for those affected families who wanted more information and support.” She attended lectures by Haematologist Dr Misha Brozovic, and the two ended up working together. Brozovic helped to get funding for Elizabeth and she made history in becoming a specialist nurse.

Elizabeth didn’t know her Nigerian father growing up, but as an adult, connected with him. He was temporarily staying in London, after the Biafran war in Nigeria which spanned 1967 - 1970 and she got to know him for eight years before he died. “That totally transformed me,” she says. Elizabeth met a whole new part of her family, and in turn developed an inner confidence and pride in her heritage. “It was like I had more substance. I just knew who I was.”

Archiving the often oral and forgotten histories of Black people is a necessary act of preservation. After encouragement from friends and family to document her incredible life, Elizabeth did just that, and wrote and self-published her own memoirs, Mixed Blessings from a Cambridge Union.

Black NHS workers still sadly face many barriers. There is “underrepresentation of Blackness in the most senior echelons within the National Health Service” as Elizabeth puts it. Elizabeth knows it’s still common for Black nurses to be passed over for career progression, losing out to people they themselves have helped to train. “That is so depressing,” Elizabeth adds. “Their expertise is being used for others, but not for themselves.”

In many ways, things are getting better, not least because conversations about race and racial injustice are being had at last. “There's been improvements. There's no question about it. But it’s still not done,” Elizabeth says.

COVID-19 is an illness that Black people are four times more likely to die from in the UK, with Black NHS workers also feeling like they have been pushed to the frontline without adequate PPE. On top of job disparities which already existed, it hasn’t been an easy year. Although Elizabeth doesn’t like to give advice, because it’s “uncomfortable to be on a pedestal sometimes,” as she put it, for young Black nurses now she believes confidence is key, as well as looking after your mental health. “The more protected you are emotionally and physically, the better you can deal with the forces that you're confronted with on a daily, regular basis.”

“I’m not that much of an optimist that racism will ever disappear,” Elizabeth admits. “But I have a huge amount of confidence in the competence of the younger, and the older generation to say: ‘Hey, this isn't acceptable.’”

It’s difficult to predict what the future holds, as we weather the storm of this pandemic, but one thing is for certain - we owe so much to trailblazers like Elizabeth Anionwu for their contribution to this country.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.

In need of some positivity or not able to make it to the shops? Enjoy Good Housekeeping delivered directly to your door every month! Subscribe to Good Housekeeping magazine now.

You Might Also Like