Liz Truss’s post-Brexit stilton deal with Japan will not ‘make Britain grate again’

There are differing visions of Britain. You hear it in the way we talk about the second world war: the nation split into those who think we were fighting Nazis and those who think we were fighting Germans. Patriots have long looked at their country and cherrypicked the parts that appeal. To some, being British is about the armed forces and the royal family. To others, it is the BBC and the NHS. To Liz Truss, national identity seems to be largely about cheese.

In 2014, Truss, then environment secretary, gave a mesmerising address to the Conservative party conference that must rank as one of the slowest speeches in modern political history. If you watch the video, everyone in it seems to be on a time delay, despite the fact they’re in the same room. But it isn’t just the awkward pauses, it’s also the tone: Truss delivering her early punchlines with the dreamy, otherworldly air of Mr Burns from The Simpsons that time he turned radioactive and kept appearing in the woods. If you judge the quality of a speech by how confused the applause is, this one takes some beating.

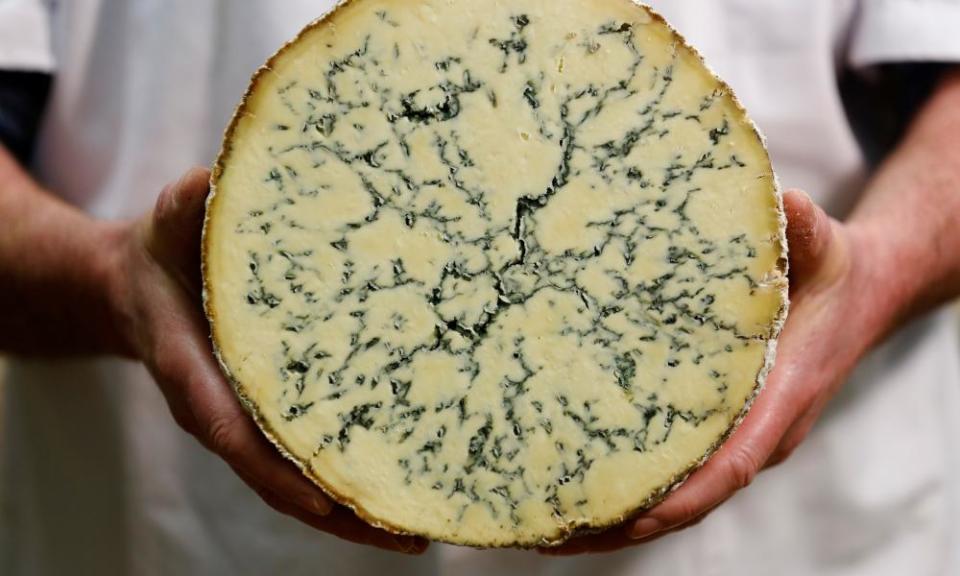

The speech’s stylistic flourishes, though, have threatened to distract from the content. It is endlessly preoccupied with cheese. A love letter to British cheese. One minute, the minister is all smiles as she announces that, “We are producing more varieties of cheese than the French!” (Hurray! Stupid sexy French.) The next, the smiles must end. “We import two-thirds of our cheese,” Truss says, with a facial expression that seems to threaten imminent violence. “That. Is. A. Dis-grace.”

Whether you agree depends to a large extent on whether you like foreign cheese. I suppose it’s that age-old trade-off between patriotism and dairy. Is it worth ruining your lunch for your country? While you could technically increase the proportion of British cheese we consume by banning Dutch gouda, you then wouldn’t have any Dutch gouda.

The self-appointed secretary of state for cheese made another intervention this week, after she insisted – very slowly and through a mouthful of Lancashire – that stilton form part of any trade negotiations with Japan. As Britain leaves the EU, the legal status of our regional products appears murky. Removing tariffs, then, would help keep prices low, should the cunning and insidious French flood the market with characteristically fraudulent stilton.

There’s a certain logic there, and there’s certainly nothing wrong in being proud of our gastronomic produce and national dishes. Last year I had fish and chips on the waterfront in Whitby that was so unequivocally fantastic I almost joined the navy.

It appears too that we are broadly discerning when doling out praise, refusing to be blinkered by culinary nationalism. In 2018, a YouGov survey regarding the most “repulsive” of our traditional foods revealed that 69% of Britons would refuse to eat tripe, two-thirds would turn their nose up at giblets, and a startling 65% would snub an eel. The top 10 makes for great reading, while doubling as a handy crib sheet of foods that Keir Starmer will eat during the 2024 election campaign to prove his patriotism.

But at the same time, I’m not sure we can base our entire national identity on cheese. That is, after all, why we didn’t send Wallace and Gromit to the trade talks.

It is a sad fact that stilton, while sumptuously crumbly, may ultimately represent something more ominous – more frightening even than the spectre of foreign cheese. Because in the context of these discussions, it is the kind of tiny detail that risks making a country look ridiculous.

Since the referendum in June 2016, we seem to have become endlessly sidetracked by parochial preoccupations, fleeing the grimmer realities of the trade talks by retreating to the realm of the village. “France needs high quality, innovative British jams,” announced Liam Fox’s department of international trade to widespread ridicule later that year, surveying the world and deciding to treat it like a county fair.

This is not just a question of image, though, or even of self-image: it is also a matter of money. While the government is reportedly desperate to prove it can negotiate a better deal with Japan than the one the EU secured, the amount at stake is actually negligible: the country currently spends just £102,000 a year on stilton. To put that into context, that is (pretty much) the same amount that a single sushi restaurant in Tokyo spent on one very large tuna in 2016.

It is still, of course, early days, and this government may yet confound the critics with its new cheese-based economy – the world acquiescing to our deliciously smelly demands as we “make Britain grate again”.

• Rick Burin is a writer from the north of England