Looking back: The Hong Kongers who left

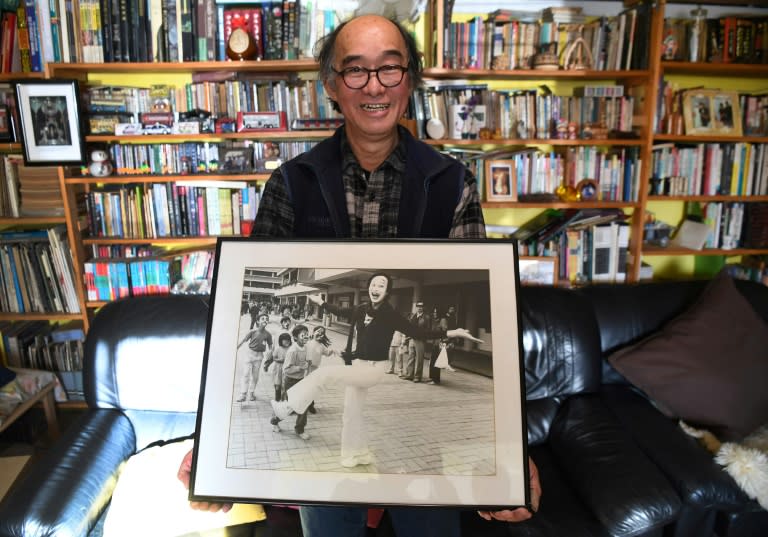

In the years leading up to the return of Hong Kong to China by Britain in 1997, thousands of residents fearful of the future under Beijing jumped ship to start a new life abroad. As the semi-autonomous city prepares to mark 20 years since the handover and fears grow that China is tightening its grip, those who left are reflecting on their decision to abandon the home they loved. Philip Fok moved to Australia in 1992 with his wife and two children because he felt unsure of what would happen after July 1 1997. Fok says China's history under the Communist Party, including the Cultural Revolution which saw purges of political opponents in the 1960s and 1970s and the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989, played on people's minds. Working as a mime artist at the time, he felt particularly vulnerable because of his need for freedom of expression. "To be free, to the artist, is very important," the 69-year-old explains. Before he emigrated, he performed a mime show at Hong Kong's City Hall theatre called: "The night before and after," dealing with pre-handover uncertainty. Fok went to Sydney where he already had relatives, but says life was hard -- he struggled to get a visa, had very little English and lived on benefits for two years. However, he eventually managed to set up a successful painting studio, which he ran until last year, and hosts a weekly Cantonese radio show in Sydney's north west, where he lives. Fok says his worst fears for Hong Kong have not materialised and argues the city is freer now than in colonial times. But he has no regrets about leaving. "In Australia nobody cares about your dress, nobody cares about your money," he says, adding that artists there are held in higher regard. In contrast to the densely packed expensive high-rises of Hong Kong, Fok lives in a four-bedroom house and is proud of the vegetable patch in his backyard. "If I have space I can think. If I have no space I can't think. I love Australia like that," he muses. - 'Better to leave' - There are no official emigration figures, but government estimates show hundreds of thousands leaving Hong Kong between 1990 and 1997, with the annual figure hitting 61,700 in 1990 and peaking at 66,200 in 1992. Australia, Canada and the United States were the top destinations and are still home to thriving Cantonese communities. Whilst emigration has dropped dramatically, numbers have recently risen again, from 6,900 in 2014 -- the year of major pro-democracy rallies -- to 7,600 in 2016. Herman Fu, 58, believes the political divisions and lack of opportunities for young people, with increased competition for jobs and salaries outpaced by the cost of living, make the situation "worse than he thought" it would be when he left. He moved to Toronto in 1987 with his wife and two-year-old son, launching a window covering business, dealing in curtains, blinds and shutters. Fu originally planned to return once he had gained Canadian citizenship. But the Tiananmen crackdown changed his mind. "My idea of the Chinese government was too optimistic and I had to rethink my decision of going back," he says. As Hong Kong boomed in the 90s, Fu felt pangs of regret as his friends rose through the ranks at their companies, but he believes overall the standard of living is better in Canada. "I'm now living in a 3,600 square feet (330 sq m) house plus the basement, with a lawn. You can't get a lawn unless you're Li Ka-shing in Hong Kong," he explains, referring to the city's richest tycoon. Fu insists he still loves Hong Kong as the place of his birth but argues it may be better for youngsters to move. He adds: "If they can't survive in their environment, or they find it hard to improve themselves, better to leave." - Next generation - Even for the children of Hong Kong's emigres, there is still a bond with the city. Justin Fung, 37, was born and raised in Vancouver after his parents were among the first wave of Hong Kongers to move there. They went to study in the late 1960s and 70s and decided to stay. Fung says the prospect of a change in China's relations with Hong Kong was causing "rumblings" even back then. The vast majority of his high school were ethnic Chinese students and there was always easy access to Cantonese food and culture. Fung refers to Hong Kong as "back home" and spent two years living and working in the city. But as the handover anniversary looms, he says he would hesitate to relocate permanently as concerns grow over Beijing interference. He says: "For myself as a father with a young child at home, I don't know if I'd want her growing up in that system." dc-dkj-at-lm/lto