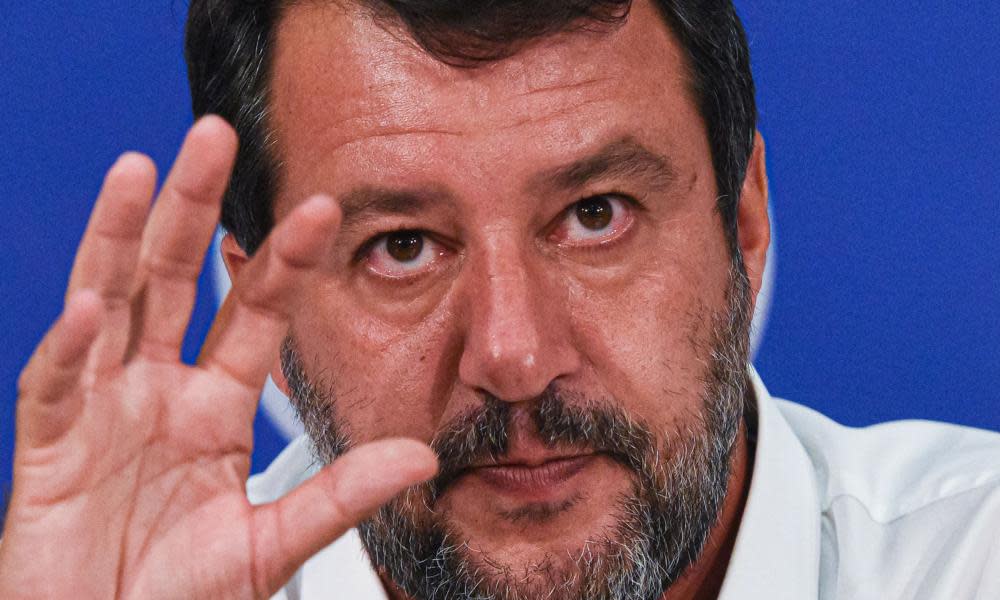

Matteo Salvini goes on trial over migrant kidnapping charges

Italy’s far-right former interior minister Matteo Salvini goes on trial on Saturday on kidnapping charges over an incident in 2019 when 116 migrants were prevented from disembarking a coastguard ship in the Mediterranean.

Prosecutors in the Sicilian city of Catania accuse the League party leader of abusing his powers to block people from disembarking from the Gregoretti coastguard boat under his “closed ports” policy.

The 47-year-old called on his supporters to descend on the courtroom in Catania to protest against what he has described as a plot against him. “I will plead guilty to defending Italy and the Italians,” Salvini told the press last week.

Fellow far-right leader Giorgia Meloni, head of the Brothers of Italy party, has promised to attend the rally, while the ex-prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, who has faced several trials himself, will send a delegation from his Forza Italia party.

Salvini’s fortunes have waned since he withdrew the League from its fractious governing alliance with the Five Star Movement (M5S) in August 2019 in an attempt to capitalise upon his high poll ratings and seize the prime ministership. His rallies are disrupted by protesters and people often challenge him in the streets.

As well as having his judgment questioned by people in his own party, he is embroiled in a series of legal wrangles, the majority connected to his tenure as a hardline interior minister.

One of Salvini’s first moves when he took office in June 2018 was to declare Italian ports closed to ships engaged in rescuing people fleeing Libya by boat. There were subsequently 25 standoffs between rescue vessels and Italian authorities, some of which became the focus of criminal investigations.

The case coming before the court on Saturday relates to a group of migrants who were rescued in the Mediterranean in two separate operations on 25 June last year after five days at sea. There were 15 unaccompanied children among them.

They were transferred to the Gregoretti on 26 July, then held on the overcrowded patrol vessel under a fierce summer sun – despite a scabies outbreak and a suspected case of tuberculosis.

The unaccompanied children were allowed off on 29 July following pressure from Catania’s youth court. The remaining migrants disembarked 31 July after Salvini said a deal had been brokered with EU countries to take them.

A few months later, the Catania prosecutor’s office placed Salvini under investigation and in February this year the Italian senate formally authorised criminal proceedings.

His defence team insists the decision to hold the people on the ship was not Salvini’s alone, but reached collectively within the government. It will be up to a preliminary hearing judge to decide whether the case is strong enough to proceed with the trial.

Observers say Salvini erred politically when he withdrew the League from government in August last year. He did not anticipate that the antiestablishment 5SM and centre-left Democratic party would put aside their deep enmity and go into coalition themselves, leaving the League on the opposition benches.

“Once Salvini reached the peak of his rise, believing himself invincible, he lost his lucidity and made one mistake after another,” said Matteo Pucciarelli, a journalist at La Repubblica and author of a book about Salvini. “After kicking himself out of the government, he is now slowly losing the leadership of the right to Meloni.”

Salvini’s attempts to keep his anti-migrant rhetoric front and centre in Italian politics this year, by linking the coronavirus pandemic to migrant arrivals, have failed to cut through.

“The strategy to exploit migrants, citing they were threatening Italy by bringing Covid-19 with them, simply did not work,” said Pucciarelli. “Migrants were no longer at the top of the minds of Italians who have had more serious issues to think about during the pandemic.”

Massimiliano Panarari, a politics professor at Mercatorum University in Rome, said Salvini’s rhetoric around invading migrants infected with Covid-19 was not credible to Italians. “In addition, the management of the pandemic in Lombardy, the region worst affected by the coronavirus – and governed by the League - has been very controversial and characterised by numerous political errors,” Panarari said. “The fact that this region was governed by Salvini’s party has had a negative impact on its popularity.”

Despite the setbacks, Salvini still has a strong support base and is expected to be able to rally thousands to his cause in Catania on Saturday. Asked recently whether he would prevent the disembarkation if he could go back in time, he replied: ‘‘It is not that I would do it again – I am going to do it again.”