A national conversation about antisemitism is long overdue - here's why

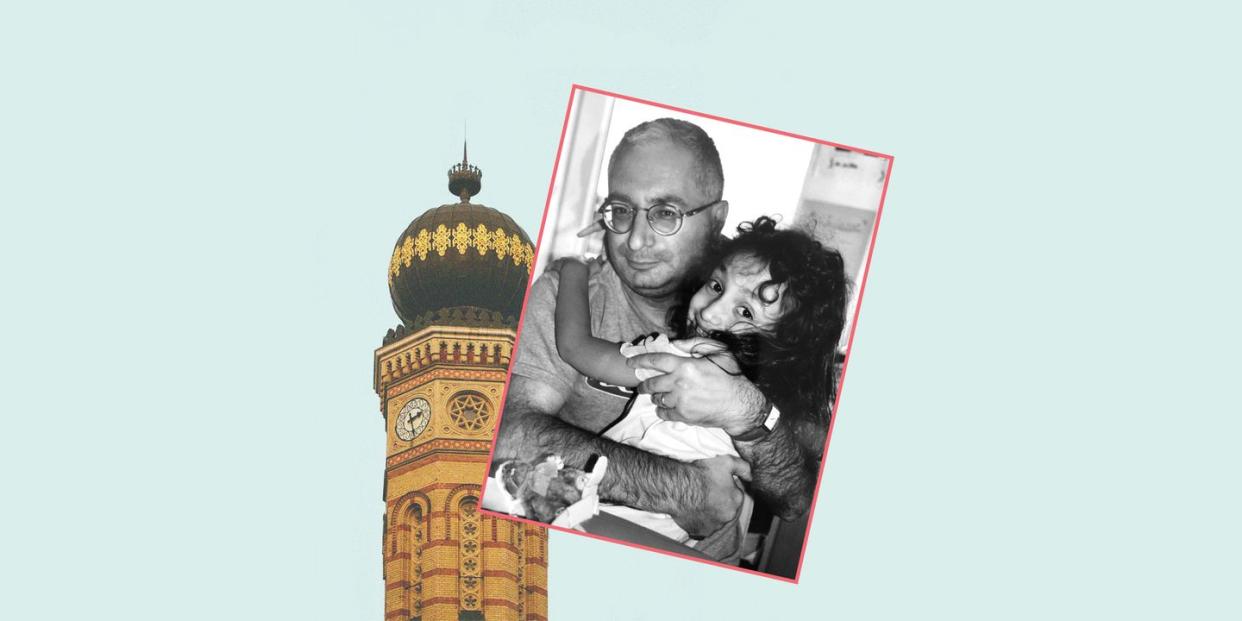

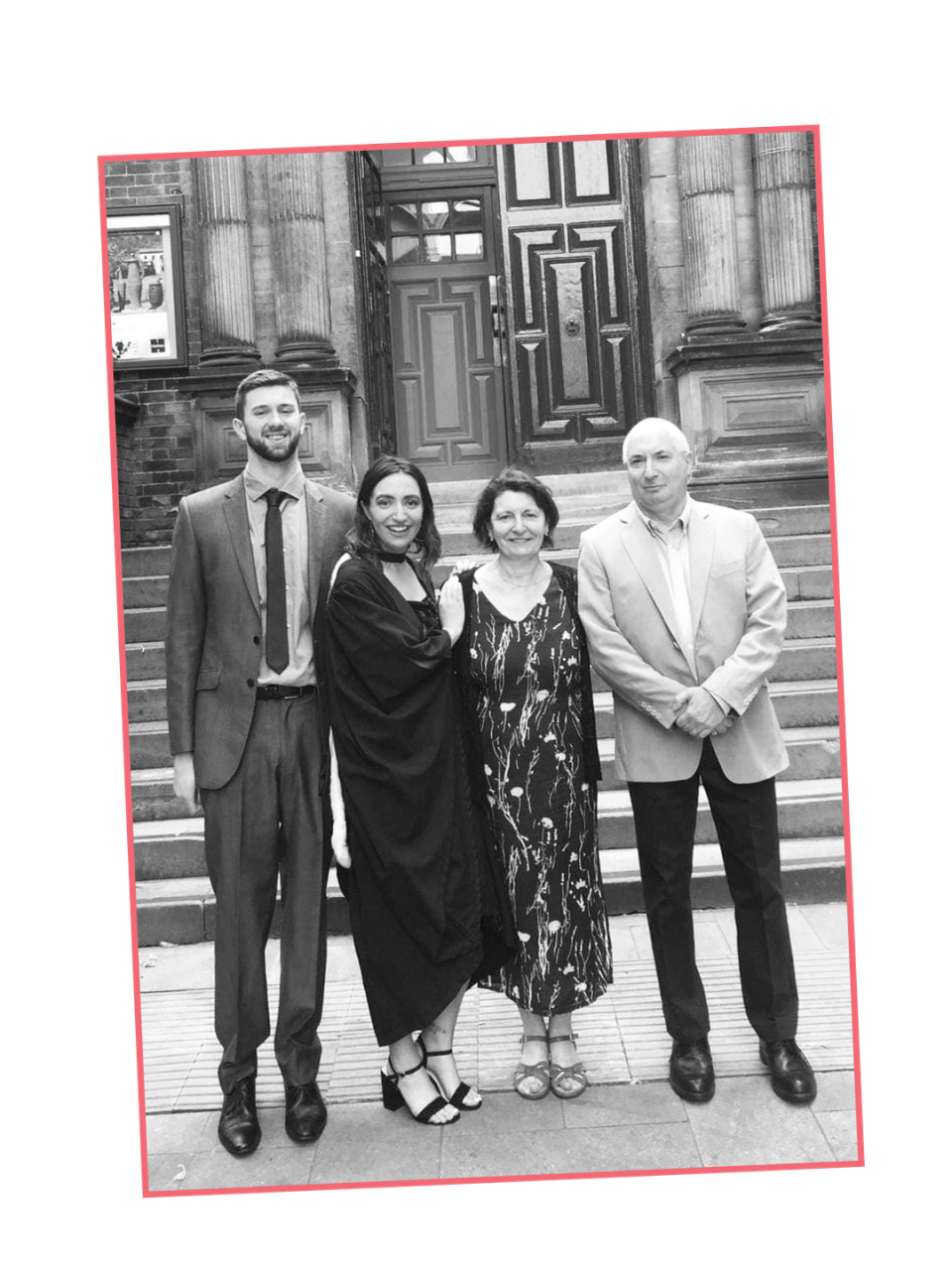

When my parents got married on a sunny day 36 years ago, two faiths and cultures came together. My mum was raised a Catholic and my dad is a Jew. While my brother and I didn’t arrive until 14 years into their marriage, the question of how they would raise us was always present. Typically, Judaism passes down the mother’s line to her children, meaning children get their Jewish status from their mother. In some forms of Judaism, this is an unchangeable rule. But in Liberal Judaism – the form my family identifies with – equilineal descent is recognised, meaning a child born of one Jewish parent is deemed Jewish, if they are raised in a Jewish way.

In the name of fairness, my parents decided to raise my brother and I in a secular home and leave us to make our own decisions on religion as we got older. Although our religious and cultural upbringing was somewhat unconventional, we are far from being the only family in the UK with one Jewish parent. Figures reported by the Board of Deputies show one in four Jews are in a partnership with a non-Jewish partner.

As a result of having a Jewish father, our Jewish heritage and culture was very present at home from a young age. Judaism is considered to be an ethnoreligion, meaning there is a connection between religion and ethnicity, so we always knew that being Jewish shaped a very big part of our DNA. We regularly attended Friday night dinners with my Jewish grandparents and celebrated the major festivals – like Passover and Hanukkah – with them. We read lots of Jewish literature, attended Jewish family events like weddings and, when we were old enough, began to explore and connect with our family background. My grandparents are Holocaust survivors, and the presence of this tragedy has undoubtedly impacted our family.

Unsurprisingly, when I turned thirteen, I decided I was Jewish. I’d grown up immersed in Jewish culture and traditions and believed in God. My parents were nothing but supportive. My mum accompanied me to visit Jewish cultural sites and at home she cooked Jewish food with me, to encourage me and learn more herself. My dad helped educate me, share his religion and enrolled me at our local synagogue. My grandparents were obviously elated I’d chosen to join the faith and made more of an effort than ever to celebrate festivals as a family.

However, I was shocked at the reaction when I announced at school that I had decided to embrace my Jewish heritage and follow the faith. After the wonderful reactions at home, I couldn’t believe the hostility I faced from some people at my school. Perhaps I was naïve but, until that moment, I hadn’t been exposed to antisemitism before. I’d heard whispers at primary school that ‘Susanne’s family are Jews,’ but I’d never assumed this was a bad thing.

Unfortunately, I was wrong. School can be a hard place if you grow up Jewish. Despite the Board of Deputies issuing advice for schools on teaching about both Judaism and antisemitism, no such system was in place at my secondary school. I remember being in a science class, my head in a textbook, when one boy turned on the gas tap and asked if I was going to ‘die like the rest of the Jews.’ I remember feeling horrified and humiliated, not just at the statement, but at the reaction. Kids around me were laughing. Apparently, this was hilarious. As someone whose extended family died in concentration camps, it's hard to express just how upsetting these 'jokes' were.

This continued throughout my school and college years. At home, I welcomed Shabbat with my family every Friday, went to synagogue every Saturday and enjoyed taking comfort in my faith. At school, I was subjected to remarks such as ‘Jews are stupid,’ ‘Jews are obsessed with money’ and ‘Jews control the world.’ I was even told by one boy it was okay to make jokes about the Holocaust, as it was ‘only’ my great-grandparents who died, and they didn’t matter.

Obviously, these were extreme examples of antisemitism I faced, but there were microaggressions, too. I was told that I ‘looked Jewish’ so many times, I started to dye my hair lighter, eventually dyeing it blonde to try and escape my ‘Jewish’ looks, something I considered to be a negative. I also straightened my hair obsessively as, having inherited curly hair from my dad, being told you have a ‘Jew-afro’ every day just makes you desperate to fit in. The saddest part of this was crying to my parents, aged 16, begging them to let me have a nose job. I was fed up of people drawing caricatures of me with a big nose, telling me I’d be ‘good looking if it wasn’t for my nose’ and teasing me relentlessly whenever they saw my dad that I’d inherited my ‘Jew nose’ from him. This embarrassment of my looks had a lasting effect, continuing well into university.

When Jeremy Corbyn was elected as Labour leader, with his links to antisemitic groups and individuals and failure to condemn antisemitism in his party, my family rallied around: we were all worried. We knew all too well what happens when antisemitism goes unchallenged; my grandparents had to flee Germany and Poland because of it. Even though my mum is not Jewish, she became worried for her Jewish husband and children. My mum’s father was from Poland, too, and had seen first-hand the discrimination Jews faced, meaning my mum fully understood the gravity of standing with her Jewish family if politics began to get out of control. During this time, antisemitism seemed to become more common and gain more press attention. The most shocking thing about this was having close friends who denied my lived experience. I tried to speak out more about the dangers of antisemitism, the dangers my family have seen first-hand, and was shouted down continually. It seemed like no-one cared and my fears were dismissed. People didn’t want to listen or, more upsettingly, chose not to listen. As antisemitism began to creep into our politics and culture in the UK, I found myself becoming more and more scared. I couldn’t understand why no-one was listening to us, taking us seriously or – worse still – saying our claims were ‘manufactured.’

In 2019, antisemitism reared its ugly head particularly aggressively towards my family. Travelling back on a train from Birmingham to Newcastle, where I lived at the time, my dad rang me to say he’d been a victim of a hate crime. I sat in shock, reduced to tears on a busy train, as he told me what had happened. While at the pub, minding his own business and chatting to his friends, a man approached him and backed him into a corner. The man proceeded to verbally attack him, telling him ‘Jews are vermin’ and ‘six million wasn’t enough.’ My dad was not targeted because he was talking about being Jewish, rather the indication was that this man believed he ‘looked’ Jewish (an assumption the Nazis used as an excuse for persecution) and proceeded to abuse him. My dad reported it to the police. Nothing happened.

My dad wasn’t alone. The Jewish charity Community Security Trust reported that antisemitic hate crimes were at an all-time high in 2019, with 1,805 incidents being recorded over the year. What happened to my dad gave my family two options. We could disassociate ourselves from our shared culture and heritage and hide our Jewishness, or we could use it to be stronger than ever and proudly display our Jewishness. We chose the latter. My mum stepped into her role as an ally in the most admirable way, telling everyone how proud she was to have a Jewish husband and daughter. My dad became more vocal on his Jewish views, especially those around Israel, a hotly contested subject. My brother embraced his ethnic Jewish heritage, finding out more about our family and using it to create inspirational blog posts. I used it to reconnect fully with my faith, enrolling at a new, Liberal Jewish synagogue in London. I also met my wonderful partner, Tom, who embraces my Jewishness unconditionally. Although he’s not a Jew, he couldn’t be more supportive, and is always keen to learn more about my faith.

Fast-forward a year, and Wiley’s antisemitic tweets took centre-stage on Twitter. Was it greatly upsetting? Yes. Did we let it deter us from embracing our faith and heritage openly? No. As a family, we condemned Wiley’s actions, and I was so pleased and relieved by the influx of support I received from friends. For what felt like the first time, people listened to me. They listened in horror at the discrimination we faced. I felt like we were beginning to be believed.

Going forward, we’re keeping up the noise. Letting the generations work to their advantages, my brother and I continue to challenge antisemitism online and share educational resources on social media, while my parents do it through in-person debate. My partner also challenges antisemitism when he sees it, flying the flag as an ally for his Jewish girlfriend. Slowly, we are seeing change, as people begin to open their eyes to what is happening to us.

However, there is still work to do. Antisemitism is still a problem, so we need our allies to listen to us and believe us when we say something is antisemitic. We need people to never stop educating themselves on what antisemitism is, so that they do not engage with it. We also need to embrace all of our Jewish communities. My Jewish ethnicity is Ashkenazi (European) meaning I have never been systematically oppressed by my Jewishness and I benefit from white privilege. Allies and the Jewish community need to do more to ensure we’re amplifying a wide variety of voices in our diverse community, including listening to our Black Jewish communities.

Being Jewish is joyous, and that is what we are celebrating, whether as Jews or allies. It’s about huge Friday night meals with the family, lighting candles and sharing stories over wine and delicious food. It’s about singing and dancing until our voices goes hoarse. It’s about affirming our connection with God, celebrating festivals and delighting in a supportive community. It’s about giving to charity and doing our best to make the world a better place.

On a personal note, to consolidate my commitment to my faith, I’ve decided to engage in a full Jewish conversion through Liberal Judaism. While I know I am Jewish ethnically and religiously, I am now so committed to being Jewish that I want it on paper, too. Liberal Judaism recognises equilineal descent, but I want there to be no ambiguity about it: I am Jewish, and I am proud of it. The antisemitism we have faced, and overcome, has only made me surer that I belong to this special and beautiful community.

Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.

In need of some positivity or not able to make it to the shops? Enjoy Good Housekeeping delivered directly to your door every month! Subscribe to Good Housekeeping magazine now.

You Might Also Like