I Was Nearly Crushed To Death In The Derailment Of Amtrak 188. Here's How I Survived.

Investigators and first responders work near the wreckage of Amtrak 188 on May 13, 2015, in Philadelphia. (Photo: Win McNamee via Getty Images)

Like many survivors of traumatic experiences, my life is divided into “before” and “after.” Passage between the two lands is a one-way ticket, and a successful journey requires not just strength, but other resilience muscles like patience, creativity, learning, experimentation and faith.

Surviving an accident is one thing. Navigating the next steps of the journey is another entirely.

On May 12, 2015, I was a passenger in the first car of Amtrak 188, coming home from an ordinary business trip around 9 o’clock at night. Shortly after pulling out of the station in Philadelphia, the conductor sped up. The train was going 106 mph when it hit the sharpest curve in the Northeast Corridor. That curve was designed for a maximum speed of 50 mph.

It had been a long day, and I had just texted my husband to say that I had made the train and would be home in New Jersey in an hour or so. He responded with an excited message about our 8-year-old son’s baseball game that evening. The text made me smile.

I stood up into the aisle to get my iPad out of my bag. As I tried to reach into my bag in the rack above my head, I lost my balance. I grew annoyed as the train started rocking back and forth. I held on to the luggage rack with both hands as we started to tilt. I screamed as I realized the train was crashing and remember nothing else.

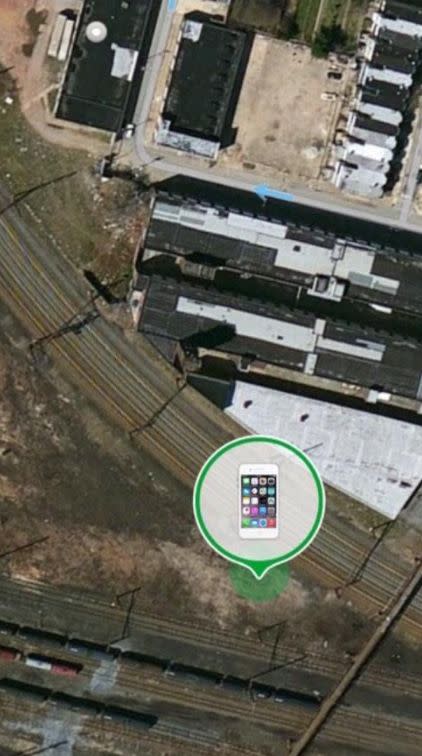

When the author's husband couldn’t reach her on the night of the crash, he used the Find My iPhone app to figure out her phone's location. This screenshot, showing it off the track at the accident site, confirmed his fears. (Photo: Courtesy of Geralyn Ritter)

My husband, Jonathan, was still looking at his phone when a CNN news alert popped up: Amtrak 188 had derailed. He had no idea of the number of my train. He called me and got sent to voicemail.

She probably has her phone on silent, he thought. He called again and texted, “please call me back.” He stared intently at his phone. Then he remembered the Find My iPhone app. A map appeared showing a train track, along with an iPhone icon 20 feet away from the rails just outside Philadelphia.

At that moment, my oldest son, Austin, walked in. “Dad, the game starts in 10,” he said, heading down to the large TV screen in our basement. Jonathan didn’t respond.

“Dad?”

Jonathan stood up abruptly and lost his filter. “I think Mom’s train crashed,” he blurted out. “I’m going to find her. You’re in charge.”

Austin stood frozen in the basement doorway as Jonathan walked out of the house.

Jonathan would spend the next nine hours searching for me around the crash site and at almost every hospital in Philadelphia. As time passed with no word from me, he realized that I was either badly injured or gone. He sunk to the floor and prayed: God, please let her be hurt.

Back at home, my 15- and 12-year-old sons had Googled “Philadelphia hospitals” and started dialing. “I’m looking for my mom,” one would say. “I think she was on the train that crashed.”

They texted my husband, “Dad, people are dead,” “Dad, have you found her?” — and later, “I need my mom.” Those texts haunt me still.

The author's husband, Jonathan, identified her in the hospital by her jewelry. (Photo: Courtesy of Geralyn Ritter)

As it turned out, I was the last surviving passenger from the train to be identified. Eight souls lost their lives that night, and hundreds were injured. As the sun rose the next day, my husband got word that there was one last Jane Doe in surgery at a Philadelphia hospital.

As he was led into the intensive care unit, Jonathan’s heart dropped. Only my eyebrows and bruised, swollen forehead were visible. My eyes were taped shut, and a ventilator covered most of my face. A cervical collar immobilized my head and neck. Surgical drapes covered my body. He didn’t recognize me until a nurse brought out Jane Doe’s personal effects in a plastic bag marked with a biohazard symbol. There was the watch that he had given me for my birthday. I was found.

I had been crushed in the crash. High-velocity blunt force trauma, they call it. Initial scans at the hospital showed my stomach above my heart and my colon under my armpit. My spleen was destroyed and bleeding uncontrollably. My diaphragm was ruptured, bladder ruptured, lungs collapsed and everything perforated, lacerated and generally screwed up. In addition, almost all the ribs on the left side were “annihilated,” in the words of my orthopedic surgeon. My pelvis was broken in half, and an object had pierced the left hip. The wound was open and dirty.

Add to all of that the broken vertebrae in my neck and back, unstable blood clots down both legs, and other wounds, and the result was the trauma surgeon’s message to my brother, a fellow doctor: I was unlikely to make it.

But I did.

I spent weeks in the ICU, enduring the awfulness of being on a ventilator and undergoing multiple marathon surgeries. I never thought I would be reduced to blinking or tapping at a kindergarten letter board to communicate. My three sons were not allowed to visit. I still wrestle with the idea that I was too scary for them to see.

Two weeks after the accident, the author's sons were finally allowed to visit her in the ICU. Her oldest, Austin, gave her the ball from his baseball game. (Photo: Courtesy of Geralyn Ritter)

I had never felt so powerless. I could control absolutely nothing about my body, my pain, my surroundings, my family or even my thoughts. I hallucinated. I was on the strongest painkillers available, but every breath hurt, all day and all night. The only thing I could do was close my eyes and pray.

My ribs were reconstructed with metal plates. Screws through my lower back and a metal bar bolted into my hips reconnected the two sides of my pelvis. I had surgery after surgery, and I suffered setbacks. Over time, though, I got stronger. They finally removed the ventilator, and I could speak. I was discharged from the ICU just weeks after the accident and far earlier than anyone had expected.

In-patient rehab was awful. As they wheeled me into the facility on a gurney, I saw old people slumped in their wheelchairs in the hall. I am embarrassed to say it, but I was horrified. I don’t belong here, I thought. I wanted out of that place, and I wanted my life back.

Good health fosters a certain arrogance. I could not accept the extent of my injuries. Even after being released to recover at home, I called my boss every couple of months to assure him that I would be back at work soon. I did this over and over for two years.

The author arrives home after being discharged from the hospital. (Photo: Courtesy of Geralyn Ritter)

I have learned that gratitude and optimism are essential recovery tools. But they must be deployed with a steely eyed realism that I was utterly lacking.

Monochromatic gratitude was what we felt at the beginning. Pain meant I was alive, and I was not paralyzed! There was no permanent brain injury! I would walk again!

When I was finally cleared to move back home, reality burst my bubble. Even while taking extraordinarily high levels of fentanyl, OxyContin, oxycodone and Lyrica all at the same time, I struggled constantly with pain. I had to ask my family to help with even the most mundane (and embarrassing) tasks.

I stared at the ceiling for hours. I would wake up like a tipped-over zombie with my hands reaching for the ceiling. I realized later why my body assumed that position during sleep. I had been hanging on to the luggage rack above my head at the time of the crash. It was my last moment of safety.

The months after my homecoming are a blur. Pain and despair are the clearest memories. I was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. I fought with my husband-caregiver. I was irritable with my sons and frustrated at my total loss of independence. I had more surgeries ― hardware in, hardware out. My husband spent hours every single week trying to keep all my prescriptions filled.

But, for the first time in my life, I was home every day when my boys walked in the door after school. I watched movies curled up with all three in my bed several times a week. I laughed and drank wine with friends devoted to getting me out of the house. I read and prayed voraciously. I was a yo-yo, experiencing some of the most intense highs and lows in my life, every single day.

The author recovers from emergency abdominal surgery in 2019. She has had dozens of surgical procedures in the years since the accident. (Photo: Courtesy of Geralyn Ritter)

After six months, I started weaning myself off the opioids. My body still hurt but had started to heal. Plus, I was sick of the suspicious glares from the pharmacists. Even worse were the humiliating urine tests that my insurance company required from me to prove that I was actually taking the drugs and not selling them.

I was not technically addicted. I never craved the drugs. But 100% of the people who take the concoction of opioids that I needed for many months will become physically dependent. Your body and your brain adjust. Thus, the reward for my determination to taper off opioids was months of nausea, chills, terrible insomnia, twitchiness and brain fog.

It took longer than I ever imagined. Medical protocol was a 25% reduction per drug per month. Intervening surgeries prolonged the timeline, but I made it and have never looked back. For years now, I have taken nothing but Advil and Tylenol.

Today, I consider myself a realistic optimist. I have embraced my life “After,” and I am incredibly grateful for this gift. I have determined to pay it forward and stay centered by seeking purpose in how I spend every day.

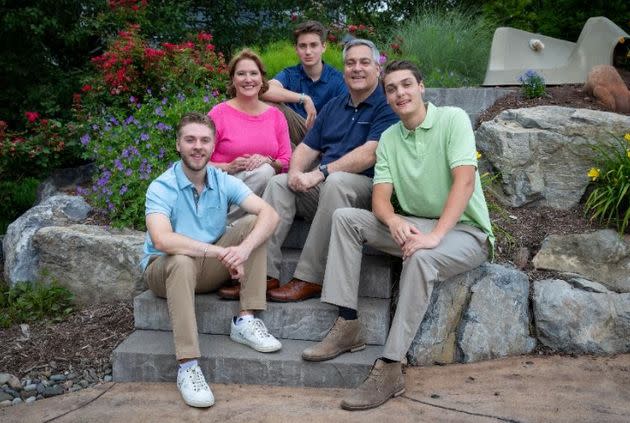

The Ritter family in 2021. (Clockwise from bottom left: Austin, Geralyn, Steven, Jonathan and Bradley) (Photo: Courtesy of Geralyn Ritter)

Hitting bottom also opened my mind to pain management alternatives like meditation, controlled breathing and gentle yoga, all of which gave me back a sense of control over my body. I am embarrassed to admit that I had always dismissed these mindfulness practices as woolly mumbo-jumbo. When I was pregnant with my oldest son, I even refused to attend Lamaze classes because ― as I told my husband ― I already knew how to breathe, thank you very much. I now know that good science backs up the efficacy of these techniques.

I also went back to work. I was fortunate that I did not have to do so to feed my family, and I spent a lot of time thinking about whether it made sense. I work in health care and ultimately decided that I was proud of what I did and that my work mattered. I am now an executive at a global company for women’s health. Standing on the New York Stock Exchange podium as we rang the opening bell and went public in 2021 was intensely meaningful. I would never be the same, but I was back.

Most importantly, the land of After is one in which relationships trump everything else. My marriage survived, and my husband and I work harder now to keep it strong. My sons and I hug each other tighter and say “I love you” more often. I text daily with my parents and siblings. And I prioritize time with the friends who brought me through the storm.

The author at her writing desk in 2021. (Photo: Courtesy of Geralyn Ritter)

I have written a book, “Bone by Bone: A Memoir of Trauma and Healing,” describing my journey and the things I wish I had known at the beginning. I hope it will help someone else whose life is upended on an ordinary day. Writing has been my attempt to salvage something good from this tragedy and my years of pain.

Survival is hard. I take no pride in surviving the night of May 12, 2015; that was due to the heroism of the first responders, the skills of the doctors and the grace of God. However, I take enormous pride in surviving 2016, 2017 and every year since.

As I write this article, I am preparing for yet another surgery, and I know two things for certain. First, I will wake up from anesthesia reaching for the ceiling. The accident is part of me. But second, I know that I will recover. I will laugh my loud, cackling laugh, and I will be back at it next month, embracing the beautiful After and living with joy.

A recognized expert in health care policy, Geralyn Ritter is executive vice president at Organon & Co., a new Fortune 500 company dedicated to the health of women. She is the author of a memoir about her recovery from the 2015 Amtrak derailment, titled “Bone by Bone: A Memoir of Trauma and Healing.”

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.