‘Nurses fell like ninepins’: death and bravery in the 1918 flu pandemic

If predictions about the spread of Covid-19 are correct, the new NHS Nightingale hospital at the ExCel centre in London’s Docklands could soon see a “tsunami” of coronavirus patients. Many will have pneumonia and require ventilators, which is why cubicles in the new 4,000-bed facility all have oxygen equipment.

It is to hoped this onslaught never comes and infections spread less rapidly than projections show. But if the worst happens, what can doctors and nurses expect?

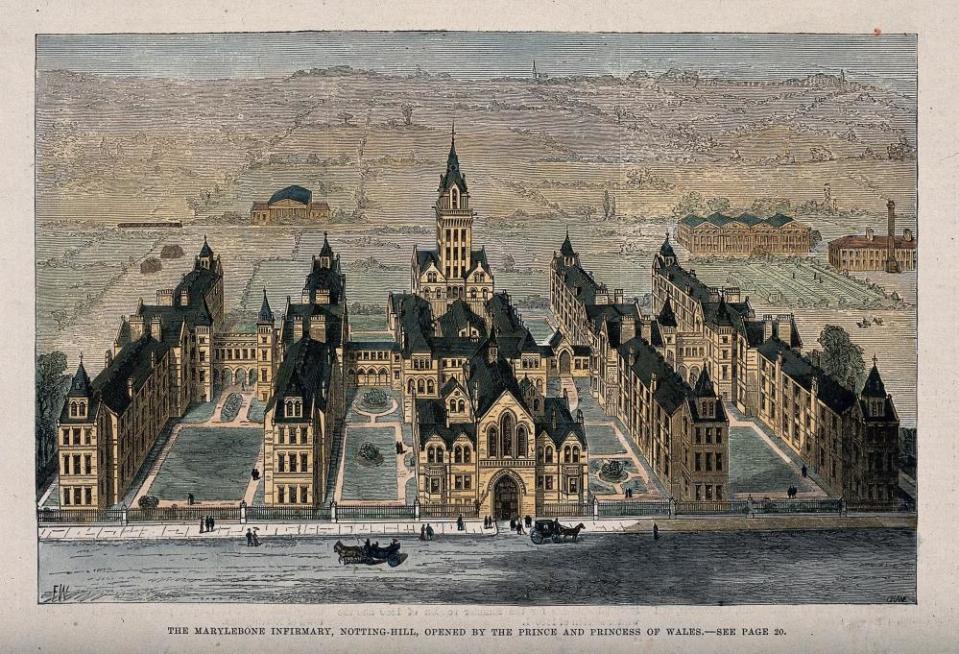

NHS workers could do worse than examine the experience of another London hospital during the Spanish influenza pandemic just over 100 years ago. Today, that hospital is named St Charles and offers walk-in care at the northern end of Ladbroke Grove, Kensington. But in 1918 it was known as St Marylebone Infirmary and had 744 beds for the “sick poor”, many of whom had tuberculosis and other chronic lung conditions.

In October 1918, as a second wave of Spanish influenza spread across Britain, its wards were inundated with pneumonia cases. According to the infirmary’s medical superintendent, Basil Hood, the hospital “literally reeled”. Hood’s harrowing frontline account is the centerpiece of an online exhibition and animation created by London’s Florence Nightingale Museum (temporarily closed).

“All training, and indeed every sort of trimming, went by the board,” Hood recalled in his notebook 30 years later. “The staff fought like Trojans to feed the patients, scramble as best they could through the most elementary nursing and keep the delirious in bed!”

In normal circumstances, St Marylebone Infirmary ought to have been able to cope, but 1918 was not a normal time: by November, when the first world war came to an end, around half of the hospital’s nurses had been called to military service. Having been decorated for bravery under fire, many nurses now fell victim to influenza.

“Each day the difficulties became more pronounced as the patients increased and the nurses decreased, going down like ninepins themselves,” Hood wrote. “Sad to relate some of these gallant girls lost their lives in this never-to-be-forgotten scourge and as I write I can see some of them now literally fighting to save their friends then going down and dying themselves.”

Hood made the nurses wear lint masks and advised them “not to interpose their faces too near the blast of those coughing”. But when it came to tending to a fellow nurse, many refused to wear the masks for fear of distressing their colleague.

In the case of one nurse, Hood noted: “Nothing I could do or say had the slightest effect in influencing her to diminish the risks to herself. She was consumed with a burning desire to save her … inevitably, the nurse developed a lung infection, dying soon after the woman she had been nursing.”

By December, Hood was exhausted and went on sick leave. When he returned in February, the epidemic was still raging and two more nurses had died, bringing the fatalities to nine.

“One poor nurse, I remember, with a terribly acute influenzal pneumonia, became so distressed she could not stay in bed and insisted on being propped up against the wall by her bed until she was finally drowned in her profuse, thin blood-stained sputum.”

Revisiting his notes in retirement, Hood called the epidemic “the worst and most distressing occurrence of my professional life”. In all, the hospital had admitted 850 influenza patients. In an era before vaccines and antibiotics, nearly half had developed pneumonia, many due to secondary bacterial infections, and 197 had died. By the time the pandemic ended in April 1919, 250,000 Britons had perished.

Of course, coronavirus is a very different pathogen from influenza. Unlike the Spanish flu, which was most threatening to adults aged 20 to 40, Covid-19 is most deadly for over-70s and those with underlying medical conditions.

Another consideration is that in 1918 almost everyone had been exposed to some type of flu before, so many people had a degree of immunity. The Spanish flu infected just a third of the world’s population. By contrast, no one had immunity to the new coronavirus, which is why it is estimated that 80% of the British population could be infected by the time the pandemic is over.

Writing shortly after the establishment of the NHS in 1948, Hood worried that despite the arrival of vaccines and new drugs such as penicillin, the hospital system would struggle to cope with a virus as destructive as Spanish flu. “Our helplessness now,” Hood wrote, “would be nearly as great.”

But that was then. At the ExCel centre, contractors have been working night and day to fit out the NHS Nightingale hospital. More field hospitals are planned at the NEC in Birmingham, the Principality stadium in Cardiff, the Manchester Central complex, the University of the West of England and the Harrogate convention centre.

Doctors and nurses working at the Nightingale and other field hospitals will have modern personal protection equipment including, for use when intubating patients or performing bronchoscopies, FFP3 respirator masks, providing the highest available level of protection.

Following the recent deaths of two British hospital consultants from Covid-19, it is to be hoped that – unlike the tragic nurse in 1918 – this time no one will choose not to use them.

Mark Honigsbaum is a medical historian and author of The Pandemic Century: One Hundred Years of Panic, Hysteria and Hubris