Obsession and Assault: The Violent Crime That Rocked Mount Holyoke

In the early morning hours of Christmas Eve last year, the Massachusetts state police were dispatched to the home of a longtime professor at Mount Holyoke College. When the on-duty trooper arrived at the home in Leverett, not far from the college, he found a horrific scene: the professor alive but severely wounded, covered in her own blood. As details of the night began to leak out in the weeks that followed, students returned to campus, but without the feeling of lightness and possibility that normally accompanies a new semester at one of America’s prettiest and most prestigious schools.

Instead, there was an almost palpable feeling that something was not right here, and perhaps hasn’t been for some time. Because there was a single fact about the incident that was now widely known: The person charged with committing the violence was another one of their beloved professors.

By March, Rie Hachiyanagi, 48, had been sitting in a cell at the Franklin County House of Correction for months, having been denied bail in late February. The professor’s arrest rocketed into news headlines just after the new year, and her former students took to Facebook to proclaim their disbelief. “I can’t imagine her doing something like this!” one wrote. “Maybe she just snapped,” another hypothesized.

But as one current student told me, “Even if you spend 30 hours a week with a professor, do you really know who they are?” Many residents of South Hadley, like Mount Holyoke’s alumnae, seemed more confused than outraged. “They are well educated, well informed,” one resident told WWLP, the local NBC News affiliate. “I guess you don’t always expect that.”

Mount Holyoke quickly distanced itself from Hachiyanagi, emphasizing that the attack occurred during winter recess and off campus, and that the alleged perpetrator has been placed on administrative leave and is banned from campus. The college produced no representatives to speak about Hachiyanagi. There seemed to be a hope that if no one uttered her name she would vanish that much sooner—a ghastly figment of the past.

But when a college is the beating heart of a small town and a landmark of American higher education, its image and the actions of its faculty become one and the same. Duty and purpose and responsibility get blurred in a way that, in this strange and harrowing instance, generates more questions than answers. Is it possible that Mount Holyoke has been employing its own Talented Mrs. Ripley all these years, or perhaps that the dark side of Rie Hachiyanagi merely caught fire on that fateful night, and dissipated just as quickly?

You won’t see many clues hiding between the lines of Hachiyanagi’s résumé at Mount Holyoke, where she chaired the Art Studio department and has been employed since 2004. But anger and resentment and personal confusion can fester beneath the surface of even the most successful public intellectual, a gaseous menace slowly expanding like a balloon ready to pop.

If that is indeed what happened here, the balloon popping left E., one of the college’s most prestigious professors, lying in a pool of her own blood, her face and skull cratered by a fireplace poker, and Hachiyanagi charged with the crime of trying to kill her. (E. declined to comment and asked that her identity not be revealed.)

“You should have known”

A spell of unseasonably warm weather overtook the Pioneer Valley of western Massachusetts on December 23, 2019. Mount Holyoke’s student body had gone home for the holidays, and the world seemed calm and inviting, like a gift received early, the surprise of holiday cheer tied tightly in a ribbon.

To hear Rie Hachiyanagi tell it, she awoke that day in a state of despair. Her live-in boyfriend, Heath Atchley, who has a Ph.D. in religion and was also once affiliated with Mount Holyoke, had left the state to visit family, and their relationship was nearing the end after a long, slow decline. (Atchley declined to comment.) She needed something, she later told police investigators, that “made her feel alive.”

She went to Enterprise Rental Car in nearby Northampton and rented a Toyota Rav4. It rode higher off the ground than her own car, as if floating above the earth. Sometime before noon she bought a poinsettia for E., who was allegedly awaiting the confirmation of a possible cancer diagnosis, and gave her the plant at her home in Leverett, a small town dotted with farms 30 minutes north of the Mount Holyoke campus. It was a quick visit—Hachiyanagi stayed on the porch—and then she was off again, first to a restaurant in Whately, on the outskirts of Amherst, and then back to Enterprise to return the Rav4.

At 4 p.m. she bumped into E. on campus; she later told investigators that they made plans to meet that night at E.’s home. Hachiyanagi went back to her own house in South Hadley, then set out again, this time to a martial arts studio in Amherst, where Atchley was the manager and head instructor. She didn’t go inside, she said, but rather stayed in the parking lot, alone. She missed him.

Hachiyanagi told investigators that she made her way to E.’s house just before midnight. When she opened the door, she said, she found E. lying on the floor, barely breathing, with gruesome injuries to her head and face. At 12:12 a.m. on Christmas Eve, she called 911 and explained that her fellow professor had been assaulted by an unknown assailant. The state police were sent to the house, and when Sergeant Stephen Burgess entered it, he found Hachiyanagi holding E., both of them covered in blood.

When E. arrived at Baystate Medical Center—her eyes swollen shut, bones broken in her face and her skull lacerated—she told police detectives a very different story. Hachiyanagi did deliver a poinsettia to E. in the morning, but E. found it strange, because she had never before invited Hachiyanagi to her home. They saw each other again that afternoon on the Mount Holyoke campus and made idle chitchat. They parted with the understanding that they would speak again after the holidays.

According to the police report, E. told investigators that she arrived at her house in Leverett at 8 p.m. Shortly afterward, something caught her eye: a shadow moving on her deck. “Who’s there?” she called. Hachiyanagi emerged from the darkness.

Hachiyanagi exclaimed that she missed E. and wanted to talk with her about her feelings. E. opened the sliding door and encouraged her colleague to come inside. Right away, within a foot of the doorway, E. said, she felt something hard hit the back of her head. She fell to the floor next to her wood stove, and Hachiyanagi kept beating her, blow after devastating blow. E. fought back. She had lost her glasses during the struggle, but she saw what Hachiyanagi was hitting her with: rocks, garden clippers, a fireplace poker, even her bare fists.

The fight produced a chaotic scene. The floor became littered with books and magazines, and spattered blood reached all the way to the porch, staining the snow dark red. E. thought she was going to die.

“Why are you doing this?” E. recalled asking.

“I’ve loved you for so many years!” Hachiyanagi allegedly replied. “You should have known!”

E. told Hachiyanagi, in an effort to appear sympathetic, that she loved her too. Hachiyanagi calmed down for a moment, but then reared back and struck E. again with the poker. She told E. that if she let her go she would surely tell someone and Hachiyanagi would go to jail. “If I go to jail,” Hachiyanagi allegedly said, “I’ll kill myself.”

E. said she kept playing along, telling Hachiyanagi she wouldn’t tell anyone, and persuaded her to call 911. Placating her attacker saved her life. When the police and paramedics arrived, E. was terrified that if she told the truth Hachiyanagi would burst into a violent rage or even try to burn down her house, so she kept her mouth shut until she arrived at the hospital.

After E. was taken away in an ambulance, state police investigators, who were still under the impression that they were dealing with a home invasion, kept Hachiyanagi on site to conduct an interview. “She was being very cooperative,” said Leverett’s chief of police, Scott Minckler, who was also on the scene. Minckler was looking out not only for E. but for the other residents of Leverett. If he needed to go out and find whoever did this, he wanted to be able to do it as quickly as possible. “Little did we know at the time that the suspect was still upstairs in the residence speaking with investigators,” he said. “You can’t put things past people. This incident appears to be some sort of crime of passion. I don’t think anybody ever saw it coming.”

In the early morning hours, after receiving E.’s statement at the hospital, the police went to Hachiyanagi’s house and placed her under arrest. In her coat pocket they found E.’s keys, cell phone, and glasses. When questioned about the violence that had apparently emerged from her unrequited love for E., Hachiyanagi said that she had blacked out; she remembered only leaving the martial arts studio’s parking lot and then finding her friend in a pool of blood, but nothing in between.

It was a bizarre element in an already strange case: Asserting that, as a result of injuries she had sustained in a near-fatal car accident she had been in—an incident she had already explored in one of her most personal art installations—Hachiyanagi claimed not to remember anything about the hours she allegedly spent trying to kill the woman she loved.

“Urges, necessities, and mortality”

Rie Hachiyanagi was born in Sapporo, Japan, and came to the United States as an exchange student, attending high school in rural Kansas. Thrown into American culture with little experience speaking English, she immersed herself in art and the opportunity for expression it afforded her. After receiving her BFA from the University of Iowa and her MFA from UC Santa Barbara, she embarked on a teaching career; inspired by the artforms of her native country, she specialized in papermaking and installation.

She taught at Alfred University in western New York and in 2004 landed a professorship at Mount Holyoke, where she received rapturous praise from her students. Last year she celebrated her 15th anniversary at the college. “She was passionate, and she expected a lot from her students. I always felt this weird joy if I could make her laugh,” said one former student. “I really knew her, but I didn’t really know her, you know? She was an incredibly private person.”

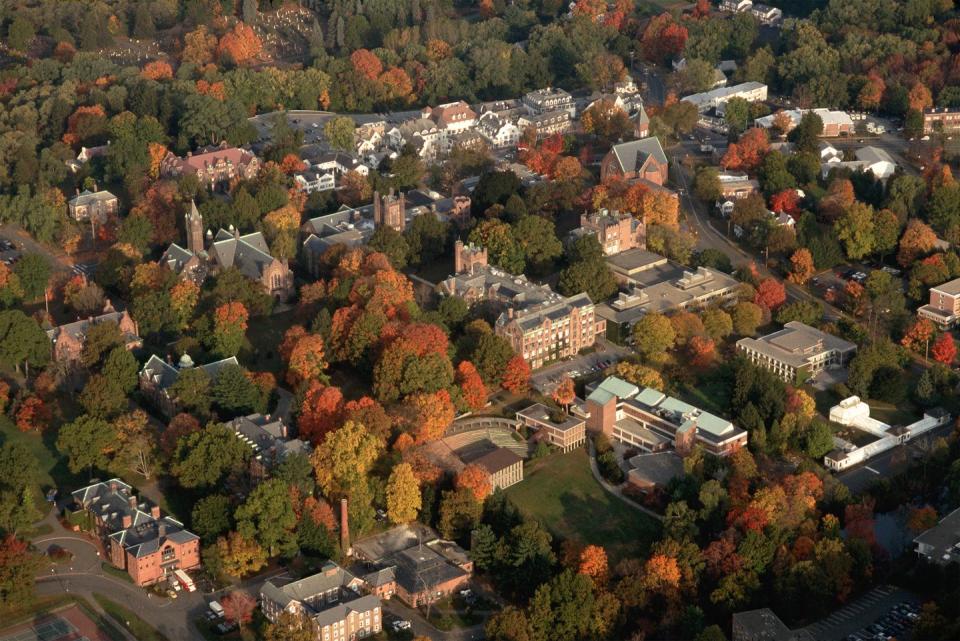

The prestige of Mount Holyoke dates back to the college’s founding in 1837 as an all-female religious seminary, a place where women could get as rigorous an education as men, where the academic standards were on par with such institutions as Harvard and Yale. Mount Holyoke became one of the Seven Sisters, a nickname coined in 1915 for a consortium of women’s colleges in the Northeast that includes Vassar and Smith.

Mount Holyoke, with its 1,000-acre campus and reputation for academic excellence, had by then already produced notable graduates including Emily Dickinson, and would over the years count Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright Wendy Wasserstein and current secretary of transportation Elaine Chao as alumnae. Illustrious faculty include former secretary of state Cyrus Vance and Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman elected to Congress.

Hachiyanagi continued to make art during her tenure at Mount Holyoke, and much of it has an autobiographical foundation, a window into herself that coincides eerily, given the crimes with which she has been charged, with the overarching subject of her work: “the absurd conflicts among urges, necessities, and mortality.”

There’s Dis(Connect), an installation of hanging paper that, she writes, “contrasts the contemporary pressure to constantly stay in touch with one another and the internal desperation that makes us disconnected.” And there’s Ritual for RED, in which Hachiyanagi wrapped pieces of shredded clothes she was wearing during the near-fatal automobile accident within small pieces of red paper, folded them into hundreds of traditional Japanese medicine packages, and displayed them in front of a bright light, producing a wall of color ranging from crimson to cranberry, maroon to mahogany.

The installation, she wrote, was a reenactment of memories lost from that car accident—in hindsight an ominous piece of art that would become part of her defense against the charge of trying to murder a fellow professor.

“I love you, therefore I’m going to kill you”

The first glimmer that something had gone horribly wrong at Mount Holyoke came in a January 3 e-mail from college president Sonya Stephens to the 2,200-person student body, mere hours before the story was in the local news. Hachiyanagi was not named, and the crime was categorized as an “altercation” that had left one professor hospitalized.

“My group chat was blowing up,” one student told me. “Who could this be? What is happening?” The administration’s lack of transparency felt similar to an earlier controversy that took place in 2018, when a tenured professor was publicly accused of sexual assaults dating back to the 1980s by three alumnae and the college refused to release his name. “It feels pretty similar,” the student said, “and while there isn’t a threat to students this time, there’s a lot of tension and silence.”

The students would soon know the extent of what had happened. The charges against Hachiyanagi—including three counts of armed assault to murder a person, three counts of assault and battery with a deadly weapon, armed assault in a dwelling, and mayhem—hit the local news that afternoon, rocking the town of South Hadley and the Mount Holyoke community.

“I was in disbelief,” a former student told me. “Trying to find the why beneath all this is going to take a while. I don’t know if anyone really knew the real Rie. She never really had friends around, or showed her humanity beyond her artwork and beyond being a professor. I feel that there’s a trope in her work around the idea of staying quiet or being silenced. It’s shocking that that release came out in such a violent way.”

Hachiyanagi has pleaded not guilty to the charges. The Northwestern District Attorney’s office and the Massachusetts state police both declined to comment, but the case has been moving forward in the courts, and, according to one law enforcement officer, some Mount Holyoke faculty members have been interviewed as part of the investigation.

On February 19, Hachiyanagi, wearing a brown knit sweater, looking forlorn with her hands cuffed behind her back, appeared in Franklin County Superior Court for a hearing to assess how dangerous she was. Assistant District Attorney Matthew Thomas argued that she should be held without bail, stating that she was responsible for the “brutal and cunning attack” against E.

He also took issue with her initial defense that she did not remember anything about the night of the attack. “Is it really believable that the defendant was in this fugue state?” Thomas asked.

Hachiyanagi’s defense attorney, Thomas Kokonowski, argued that she should be released on bail, and he disputed the prosecution’s theory of Hachiyanagi’s guilt. “The motive that the commonwealth is putting forth is that my client, out of the blue, shows up and says to the alleged victim, ‘I love you, therefore I’m going to kill you,’” Kokonowski told the court that February day, adding that “there’s a lot that doesn’t make sense from the very beginning.”

Kokonowski also brought in a character witness, Lee Bowie, retired dean of Mount Holyoke, who said that he had overseen Hachiyanagi’s promotions at the college and had once taken her to a Boston Red Sox game; Bowie did admit, however, that he had not seen Hachiyanagi in about two years. Ultimately, Judge Mark D. Mason decided to hold Hachiyanagi without bail, and she will await trial from the county jail. Her next court date, a pretrial conference, is scheduled for April 22.

Meanwhile, the crime and the mystery surrounding it have become a dark crevice in the façade of Mount Holyoke’s rarefied, ivy-cloaked history. “As soon as you walk inside those gates, it’s like a force field to the outside world,” one student told me. “But within all that brick and mortar and prestige that we have, there’s a beautiful and amazing school filled with secrets.”

This story appears in the May 2020 issue of Town & Country.

You Might Also Like