One in five Australian scientists planning to leave the profession, survey shows

Nearly one in five scientists in Australia are planning to leave the profession permanently, according to a new survey, which also reveals a 17% gender pay gap among those who responded.

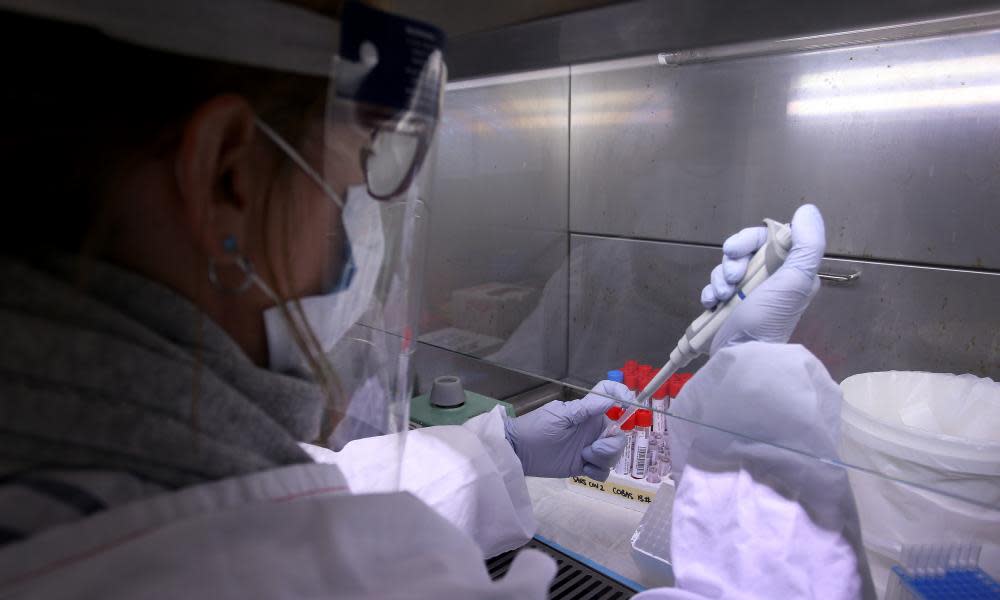

The survey, based on answers from 1,464 scientists, provides an insight into challenges in the science workforce at a time when it has been at the forefront of responding to Covid-19 but has also come under intense strain.

Professional Scientists Australia – one of the two professional organisations that carried out the research – said the results “deepened concerns that the impact of the Covid-19 health crisis will further exacerbate” the underrepresentation of women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (Stem) fields and the gender pay gap.

Conducted in May with Science & Technology Australia, but released on Monday, the survey found almost one in five respondents, or 18.3%, indicated they intended to leave the profession permanently – but this sentiment was more pronounced among women.

The proportion of respondents planning to leave the science workforce permanently was 21.7% among women compared with 15.7% among men.

“Female respondents more commonly cited lack of recognition or opportunities, lack of career advancements and parenthood as reasons for considering permanently leaving the profession than their male counterparts,” said a report by the two groups that represent scientists and technologists across Australia.

The report also said female scientists who responded to the survey earned on average 82.9% of male respondents’ earnings, representing a gap of 17.1%.

It attributed this gap to a mix of factors, including women’s concentration in less-senior roles, and the science workforce having fewer women than men aged over 40.

Annalese Jack, Brisbane-based a fertility scientist, said last week was her final week in her role.

“I am one of those people who has made the change now – I’m going to join the union movement and hopefully continue to advocate for women in Stem, although I feel a little guilty actually being one of the people who’s leaving,” the embryologist told Guardian Australia.

“I found initially I was able to manage continuing my career with having children, but as my children got older the sort of work-family conflict increased, and I think that was probably more when they started school.”

Science could be “very black and white” with “quite rigid structures”, Jack said.

“If you put an experiment or something in to incubate overnight, you have to be there in the morning to get it, and when that combined with the school schedule, the uniform shop open one morning, one day a week, things were getting really difficult for me to manage.”

Jack said she had looked into changing to business side of operations, but felt “pigeonholed”. When she looked for opportunities outside the fertility business, she was seen as “overspecialised”.

Jack said she did not think the gender pay gap was intentional. “We’re certainly paid the same for the same job – but I think perhaps the males with less family pressures are able to progress into those higher up positions more easily,” she said.

“Often if you drop down to part-time, you’re potentially seen as not taking your career as seriously.”

On the potential exodus from the sector, Jack added: “A lot of fertility scientists were stood down during the pandemic and I think spending time at home gave people a really clear chance to think about what they wanted.”

Katie Havelberg, a Brisbane-based medical scientist, agreed that when female scientists reached a certain level in their career, they often found limited opportunities for advancement and access to increased pay.

“It’s not surprising that a high number of women compared with men were planning to leave the industry,” Havelberg said.

The chief executive of Professional Scientists Australia, Jill McCabe, said the report confirmed that teaching more girls and women Stem skills and increasing the number of female graduates was not enough to solve the problem.

“Future Stem strategies must focus on improving the participation and retention of women at the workplace level,” McCabe said in a statement.

The chief executive of Science & Technology Australia, Misha Schubert, said Australia could not afford to lose the wealth of talent in science.

“With the world’s hopes pinned on scientists to find us a way out of the pandemic, the value of science has never been clearer – yet our scientists don’t always feel that recognition,” she said.

To this end, Schubert urged Australians to tweet a shoutout to an Australian scientist this week using the #CelebrateAScientist hashtag. Scott Morrison is due to announce the prime minister’s prizes for science on Wednesday.

The report said the survey’s timing in May meant it captured only the initial impact of the pandemic on wages – with salaries likely to be hit over the coming 12 months.

The May exercise found base salaries for full-time professional scientists surveyed grew by 2.2% on average over the previous year – but one in four respondents had not had a pay increase over that time.

Preliminary results from the same survey, released in August, showed the sector had been under strain during the pandemic due to job cuts, pay freezes, changes to work roles, and the impact of juggling working from home while caring for children.

The findings come amid thousands of job losses across Australian universities, which have seen revenue plummet due to the loss of international students and an inability to access the government’s jobkeeper wage subsidy.

This month’s federal budget included an extra $1bn for university research to forestall damage to the sector caused by the drop-off in international students.

The budget papers argued the investment would “help avoid lasting damage to the research sector, while the treasurer, Josh Frydenberg, argued the $1bn was “backing our best and brightest minds whose ideas will help drive our recovery”.