How do pandemics end? In different ways, but it’s never quick and never neat

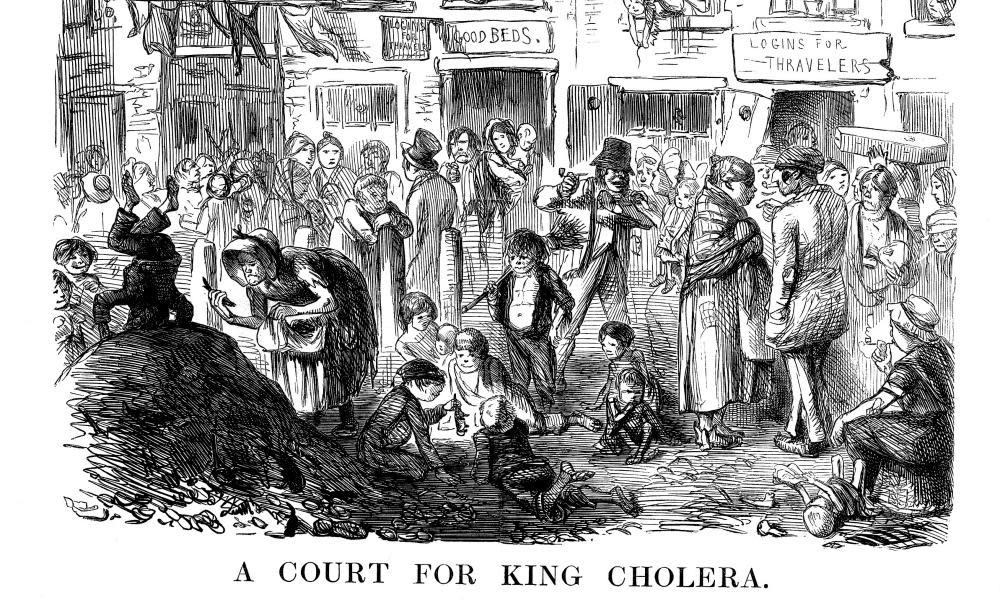

On 7 September 1854, in the middle of a raging cholera epidemic, the physician John Snow approached the board of guardians of St James’s parish for permission to remove the handle from a public water pump in Broad Street in London’s Soho. Snow observed that 61 victims of the cholera had recently drawn water from the pump and reasoned that contaminated water was the source of the epidemic. His request was granted and, even though it would take a further 30 years for the germ theory of cholera to become accepted, his action ended the epidemic.

As we adjust to another round of coronavirus restrictions, it would be nice to think that Boris Johnson and Matt Hancock have a similar endpoint in sight for Covid-19. Unfortunately, history suggests that epidemics rarely have such neat endings as the 1854 cholera epidemic. Quite the opposite: as the social historian of medicine Charles Rosenberg observed, most epidemics “drift towards closure”. It is 40 years since the identification of the first Aids cases, for instance, yet every year 1.7 million people are infected with HIV. Indeed, in the absence of a vaccine, the World Health Organization does not expect to call time on it before 2030.

However, while HIV continues to pose a biological threat, it does not inspire anything like the same fears as it did in the early 1980s when the Thatcher government launched its “Don’t Die of Ignorance” campaign, replete with scary images of falling tombstones. Indeed, from a psychological standpoint, we can say that the Aids pandemic ended with the development of antiretroviral drugs and the discovery that patients infected with HIV could live with the virus well into old age.

The Great Barrington declaration, advocating the controlled spread of coronavirus in younger age groups alongside the sheltering of the elderly, taps into a similar desire to banish the fear of Covid-19 and bring narrative closure to this pandemic. Implicit in the declaration signed by scientists at Harvard and other institutions is the idea that pandemics are as much social as biological phenomena and that if we were willing to accept higher levels of infection and death we would reach herd immunity quicker and return to normality sooner.

But other scientists, writing in the Lancet, say the Great Barrington strategy rests on a “dangerous fallacy”. There is no evidence for lasting “herd immunity” to the coronavirus following natural infection. Rather than ending the pandemic, they argue, uncontrolled transmission in younger people could merely result in recurrent epidemics, as was the case with numerous infectious diseases before the advent of vaccines.

It is no coincidence they have called their rival petition “the John Snow memorandum”. Snow’s decisive action in Soho may have ended the 1854 epidemic, but cholera returned in 1866 and 1892. It was only in 1893, when the first mass cholera vaccine trials got under way in India, that it became possible to envisage the rational scientific control of cholera and other diseases. The high point of these efforts came in 1980 with the eradication of smallpox, the first and still the only disease to be eliminated from the planet. However, these efforts had begun 200 years earlier with Edward Jenner’s discovery in 1796 that he could induce immunity against smallpox with a vaccine made from the related cowpox virus.

With more than 170 vaccines for Covid-19 in development, it is to be hoped we won’t have to wait that long this time. However, Professor Andrew Pollard, the head of the Oxford University vaccine trial, warns that we should not expect a jab in the near future. At an online seminar last week, Pollard said the earliest he thought a vaccine would be available was summer 2021 and then only for frontline health workers. The bottom line is that “we may need masks until July”, he said.

The other way the pandemic could be brought to a close is with a truly world-beating test-and-trace system. Once we can suppress the reproductive rate to below 1 and be confident of keeping it there, the case for social distancing dissolves. Sure, some local measures might be necessary from time to time, but there would no longer be a need for blanket restrictions in order to prevent the NHS being overwhelmed. Essentially, Covid-19 would become an endemic infection, like flu or the common cold, and fade into the background. This is what appears to have happened after the 1918, 1957 and 1968 influenza pandemics. In each case, up to a third of the world’s population was infected, but although the death tolls were high (50 million in the 1918-19 pandemic, about 1 million each in the 1957 and 1968 ones), within two years they were over, either because herd immunity was reached or the viruses lost their virulence.

The nightmare scenario is that Sars-CoV-2 does not fade away but returns again and again. This was the case with the 14th-century Black Death, which caused repeated European epidemics between 1347 and 1353. Something similar happened in 1889-90 when the “Russian influenza” spread from central Asia to Europe and North America. Although an English government report gave 1892 as the official end date of the pandemic, in truth the Russian flu never went away. Instead, it was responsible for recurrent waves of illness throughout the closing years of Queen Victoria’s reign.

Even when pandemics eventually reach a medical conclusion, however, history suggests they may have enduring cultural, economic and political effects.

The Black Death, for instance, is widely credited with fuelling the collapse of the feudal system and spurring an artistic obsession with images of the underworld. Similarly, the plague of Athens in the 5th century BC is said to have shattered Athenians’ faith in democracy and paved the way for the installation of a Spartan oligarchy known as the Thirty Tyrants. Even though the Spartans were later ejected, Athens never regained its confidence. Whether Covid-19 leads to a similar political reckoning for Boris Johnson’s government, only time will tell.

• Mark Honigsbaum is a lecturer at City University of London and the author of The Pandemic Century: One Hundred Years of Panic, Hysteria and Hubris