Plant inspectors and rising prices: UK garden industry set for Brexit shock

The UK’s love of horticulture has grown during the coronavirus pandemic, but avid gardeners are being warned of a Brexit shock, with rising prices, potential plant shortages and even the need for plant inspectors at nurseries.

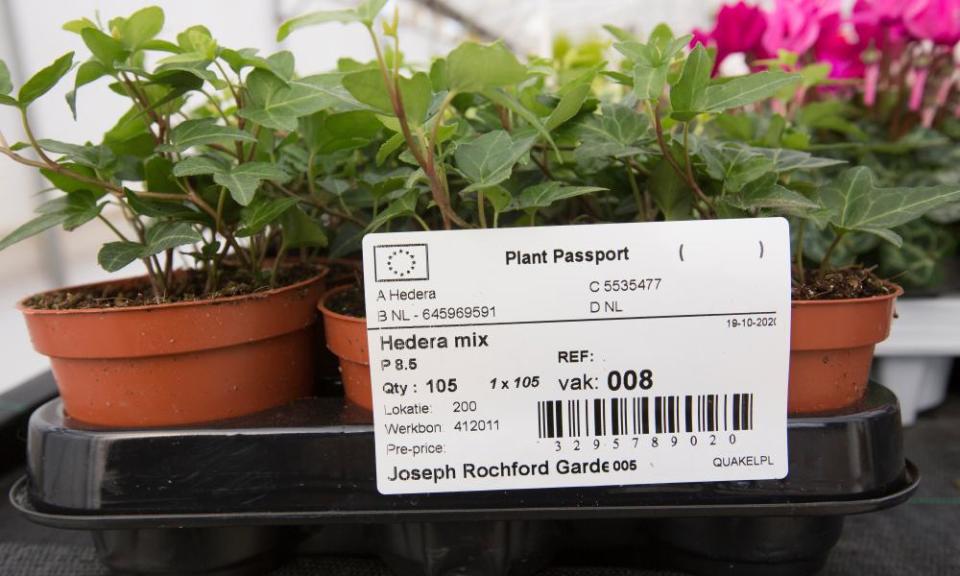

Every year 55,000 trucks loaded with plants arrive in the UK from the Netherlands alone. Each individual pot or hessian root wrap bears an EU “plant passport”, which allows frictionless cross border trade.

But from 1 January, these passports will no longer be valid in Britain. Importers will need to complete their own checks to comply with new UK regulations to certify that each plant is disease- and pest-free, adding costs and delays to suppliers who will now have two layers of red tape to contend with – one for EU customers and one for British nurseries.

Andy Moreham, the sales and marketing manager at Joseph Rochford Gardens wholesale plant nursery in Hertfordshire, said the new regime would choke off some supplies from industrial suppliers in the Netherlands.

“They are now going to be exporting at additional cost and some of our suppliers have told us they will not want to do this and they want to just sell their products to the EU,” he said. “I feel sorry for them because they have nothing to do with the UK government’s decisions, it’s going to be difficult for them and for us as it’s been nice to have built up a close working relationship with them over decades.”

Strolling through the remainder of this season’s lavenders, hydrangeas and hedging from the Netherlands, Moreham pointed out the EU flags and passports on the plants. He said it was the consumer who would pay for Brexit. “Most likely we will see a 10% increase in costs.”

It is no surprise that in a nation of gardeners, the horticulture industry is huge, worth £5bn a year, yet it does not receive the same attention in Brexit talks as farming and fishing.

Joseph Rochford Gardens is a small family business with a turnover of about £4m to £5m. But like many nurseries it relies heavily on imports, with about £1.5m worth of stock coming from the EU. The doubling up of regulations – one for EU buyers and one for British buyers – seemed unnecessary, said Moreham.

Some suppliers have told the nursery it could need plant inspectors on site every day to produce the quantity of certificates that would be required for cross-channel trade under the new “independent UK” regulatory system. Each certificate will cost £180 to the supplier, enough to wipe out the small margins on sales.

In addition to the health certificates, suppliers will be subject to health inspections at ports and inland border control posts, which are being set up under Michael Gove’s border operation model.

Suppliers will also have to supply export declarations to EU authorities for the first time, coupled with customs documentation on arrival in the UK for the first time.

“The cost of inspection at each end, the increased cost of transport, the cost of hiring agents to register each import on the various new software systems for imports, it is likely that there will be a 10% increases in costs,” Moreham said.

“Plants are perishable, if our plants get stopped at the harbour for God knows how long, then they will dry out and if they are delayed for a day or two or they decide they need to put them in quarantine, they could deteriorate or die.”

Joseph Rochford Gardens is adding £150,000 worth of seedlings and cuttings to its December orders to beat the potential chaos and supply shortages in January, when it would usually grow on for saleable produce in March and April.

“Covid has cost us £1m in sales and has long-term consequences,” he said, adding that it had not left any money for capital expenditure that would be needed across the industry to do what the government would like them to do: develop a homegrown business to match that of the Netherlands and obviate the need for so many imports.

Moreham’s immediate concern is delays at the borders and a second wave of coronavirus destruction.

“Horticulture has been the poor relative to agriculture and doesn’t have the same clout. But we are a multibillion-pound industry, a successful industry that is only going to grow. We are going to have to look at how the industry changes and grows more for our market.”