Quadriplegic man regains use of arm in medical first: study

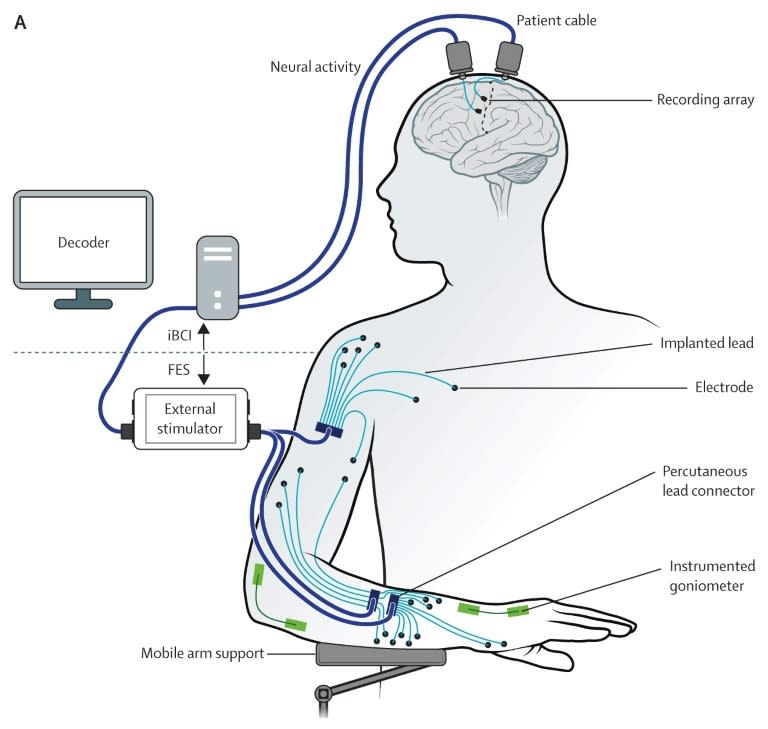

A decade after a bike crash that left an American man paralysed from the shoulders down, he can again feed himself, researchers hailing a medical first reported Wednesday. The remarkable advance hinges on a prosthesis which circumvents rather than repairs his spinal injury, using wires, electrodes as well as computer software to reconnect the severed link between his brain and muscles. "To our knowledge, this is the first instance in the world of a person with severe and chronic paralysis directly using their own brain activity to move their own arm and hand to perform functional movements," lead study author Bolu Ajiboye of Case Western Reserve University in the United States told AFP. The study's only patient, 56-year-old Bill Kochevar, has two surgically-implanted clusters of electrodes -- each no bigger than a baby aspirin -- in his head to read his brain signals, which are interpreted by a computer. His muscles then receive their instructions from electrodes in his arm. After around ten years of immobility, this has allowed Kochevar to sip coffee, scratch his nose and eat mashed potatoes in laboratory tests. To overcome gravity that would otherwise prevent him from raising his limb, Kochevar uses a mobile support, which is also under his brain's control, according to the study published in The Lancet medical journal. Though the prosthesis remains experimental, the researchers hope their work will one day help people with paralysis do daily tasks on their own. - 'Groundbreaking, but' - Scientists are seeking, but have not found, a way to mend spinal cord injuries that result in paralysis. In the meantime, they are developing work-around solutions that reconnect the brain to the body's muscles. Previous efforts have also used prostheses. One reported on last year was linked to electrodes on the skin that helped an American man, Ian Burkhart, with less severe paralysis open and close his hand, the authors said. Other methods allow participants to control a robotic arm using their thoughts. For Kochevar the process of learning to use the prosthesis started by him practicing with a simulation of an arm that appeared on a screen. From there he quickly progressed to using his mind to direct the movements of his arm. During the training he told researchers: "I just think 'out'... and it goes." But the technology has limitations, including that Kochevar needs to watch his arm at all times in order to control it. This is because he has lost his intuitive sense of his limb's movements and location, known as proprioception, due to the paralysis, according to the scientists. Kochevar became a quadriplegic when he crashed his bicycle into the back of a truck on a rainy day, which was about eight years before the electrodes were implanted in his brain in 2014. The hope brought by the study have had a profound impact. "For somebody who's been injured eight years and couldn't move, being able to move just that little bit is awesome to me," Kochevar said. "It's better than I thought it would be." A lot of work remains before this prosthesis could be widely used. "This study is groundbreaking," wrote Steve Perlmutter of the University of Washington in a piece commenting on the case. "However, this treatment is not nearly ready for use outside the lab." For that, the system would need improvements, including making it wireless, as well as increasing the longevity and effectiveness of the brain implants, Ajiboye said. "While it is proof-of-concept... this technology could very well make its way to become the standard of clinical care for persons with chronic and complete paralysis," he added.