Raymond Goethals: Marseille's messiah who toppled mighty Milan

The first final after the rebranding of Europe’s premiere club competition as the Champions League took place 27 years ago this Tuesday. It was a stinker. Marseille, who beat Milan 1-0 in Munich, had contested an even grimmer final two years previously, losing the European Cup on penalties to Red Star Belgrade. Two lustreless showpieces are part of the reason why Marseille’s then manager, Raymond Goethals, is seldom recalled as a great outside France and his native Belgium despite an extraordinary career spanning nearly four decades.

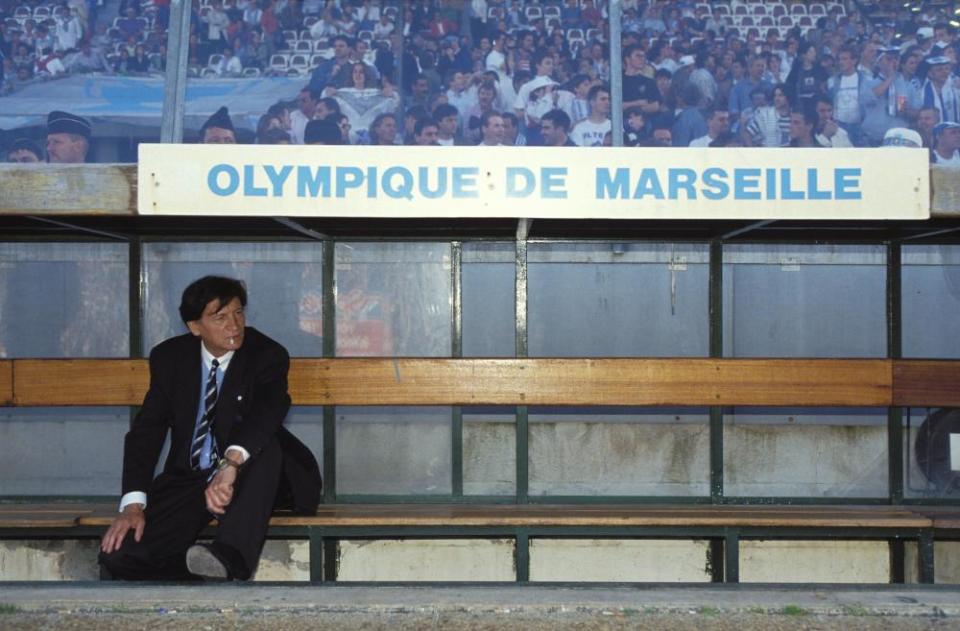

But there are other reasons. He was a canny coach and an entertaining character who nearly always had a cigarette in his mouth, with his distinctive hair visibly dyed black , while wearing, most match days, a billowing anorak that superstition forbade him from washing. Goethals tended to be overshadowed during his time at Olympique Marseille, however, by the club’s outrageous owner, Bernard Tapie, who had bought OM in the same week in 1986 that Silvio Berlusconi took over Milan. For years European football was a battleground between two colossal egos seeking a form of validation that they could not get through their business and political conquests. For Tapie, who also fancied himself as an actor, turning Marseille into European champions was “like taking [Jack] Nicholson’s role in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest”.

Even more significant for Goethals’ legacy, however, is the fact that two of his greatest triumphs – with Marseille in 1993 and his Belgian title with Standard Liège in 1982 – were soiled by corruption. He was not implicated in Marseille’s cheating: Tapie and others were sentenced to prison for bribing players from Valenciennes to go easy in their last domestic match before facing Milan. But that scandal bore uncomfortable similarities to Standard’s practice in 1982, when Goethals was found to have helped bribe players from his team’s last domestic challengers, Waterschei, before facing Barcelona in the Cup Winners’ Cup final (Barça ultimately beat Standard 2-1). Goethals had to resign from Standard and was banned from working in Belgium for a year. He always denied any wrongdoing and devoted just one short paragraph of his 1994 autobiography to the affair, dismissing it as “political score settling”.

There was more than a whiff of the wild west about Belgian football back then. Standard’s nearest pursuers in 1982 were Anderlecht, whom Goethals had previously managed successfully and whose president, Constant Vanden Stock, would later bribe a referee to help them beat Nottingham Forest in the 1984 Uefa Cup semi-finals.

For all the murk, Goethals was clearly an excellent coach. He had shown that ever since the end of his so-so goalkeeping career, after which he took a trio of small clubs from obscurity to prominence before, in 1966, being appointed assistant manager of Belgium under Vanden Stock. Two years later Vanden Stock left to move into club administration and Goethals took the top job. He immediately ended Belgium’s 16-year absence from the global stage by guiding them to the 1970 World Cup, then led to third place in the 1972 European Championship.

One of Goethals’ many nicknames was “Raymond-La-Science” thanks to his ability to devise tactics to thwart the most gifted opponents; usually the plan involved a high defensive line, meticulous use of the offside trap and clever pressing, ploys he repeated throughout his career, including against Milan.

One of his most satisfying feats came at a time when connoisseurs were starting to swoon over the Netherlands’ “total football” revolution. Johan Cruyff’s team failed to score home or away against Belgium in the qualifiers for the 1974 World Cup and would not have made it to the tournament if a perfectly good last-minute goal by Belgium in Amsterdam had not been wrongly ruled out for offside. The Netherlands squeaked through to the finals on goal difference, as Goethals’ team became the first to fail to qualify for the tournament despite not conceding a single goal.

Yet Goethals’ teams could attack. After moving back into the club game he guided Anderlecht to a 4-0 victory in the 1978 Cup Winners’ Cup final and two impressive Super Cup wins, a 5-3 aggregate destruction of Bayern Munich in 1976 and a 4-3 defeat of Liverpool in 1978.

Then came spells managing in France and Portugal before glory and disgrace with Standard. He was not in the oubliette for long. Racing Jet, in his hometown of Brussels, hired him in 1985 before he left for Bordeaux, where Goethals often made life difficult for Tapie’s Marseille on the pitch and mocked them in the press. So a blissful union was not necessarily on the cards when Tapie asked him to replace Franz Beckenbauer as Marseille manager midway through the 1990-91 season.

But they prospered together, even if sparks flew constantly over the next three years. Goethals won three French titles (though the were subsequently stripped of the 1993 one), reached two European finals and was twice ousted as manager without actually being sacked, instead being moved upstairs for a few months before returning to the dugout when his replacements, Tomislav Ivic and Jean Fernandez, fell short of Tapie’s expectations.

“I was never sacked in a career lasting nearly 40 years,” Goethals once recalled when asked about his relationship with the tempestuous Tapie. “But I was shown the door several times a week at Marseille.”

Related: Daniele Massaro: ‘The Marseille defeat filled us with grief. But we came back’

Goethals was nearly 70 when he stepped into the Marseille cauldron and he was not afraid of Tapie, whom he knew needed him. With few exceptions, notably Eric Cantona, the players affectionately called him papy (grandad) and liked him for his tactical cunning, his humour and the fact that he gave them plenty of freedom outside match days, an important valve that relieved the incomparable pressure of playing for Marseille and Tapie.

Marseille were first drawn against Berlusconi’s Milan in the quarter-finals of the 1991 European Cup. Goethals said Tapie rang him near 3am every morning for the next three months to ask: “Are you planning the match?” to which Goethals invariably replied: “I’m trying to,” before hanging up. When the first leg at San Siro finally came around, what Goethals and his team did was remarkable.

Milan were Europe’s kings, continental champions two years on the trot. Marseille pitched up in Italy with only 14 players instead of the permitted 16, as Goethals omitted Cantona and Jean Tigana, having fallen out with both. “Cantona simply did not fit into my team,” he later said, years after being vindicated by the consistently thrilling attacking trident of Chris Waddle, Jean-Pierre Papin and Abedi Pele.

The game at San Siro heralded OM’s arrival as a European force. Marseille conceded a sloppy early goal but recovered to control the match in a way visitors never did against Arrigo Sacchi’s lords. Milan escaped with a 1-1 draw. Marseille won the home leg 1-0 thanks to a volley by Waddle. When the floodlights failed temporarily one minute from the end, Milan refused to play on, a desperate stance that earned them a ban. Marseille had not merely dethroned them, they had rendered them ridiculous. Tapie was in raptures.

But Marseille grew too sure of themselves after that and failed to finish the job in the final, where Red Star frustrated them before prevailing in a shootout. Goethals later lamented that his team had been too dominant and should have relented a little to coax Red Star forward.

Two years later Goethals’ men finally atoned and became the first, and so far only, French club to conquer Europe.

The side of 1993 was less spectacular, with Waddle sold to Sheffield Wednesday and Papin to Milan, but they were more wily even if they let slip a 2-0 lead to draw with Rangers at Ibrox in the tournament’s group phase. Marcel Desailly ensured the imperious Carlos Mozer was barely missed, while Fabien Barthez was a big improvement on Pascal Olmeta in goal and Didier Deschamps and Frank Sauzée improved midfield. And Pele, nurtured much more by Goethals than he had been by Beckenbauer, remained a delight.

The Ghanaian was the best player in the 1993 final, running Paolo Maldini ragged and taking the corner that led to the winning goal by Basile Boli. At the age of 72, the manager frequently called “Columbo” by the Belgian press because of his style had solved his biggest case. Soon, though, his success was linked with crime again, as word of the match-fixing against Valenciennes broke.