Who Will Represent Us at the Polls?: A Primer on the Forgotten Sister Suffragettes

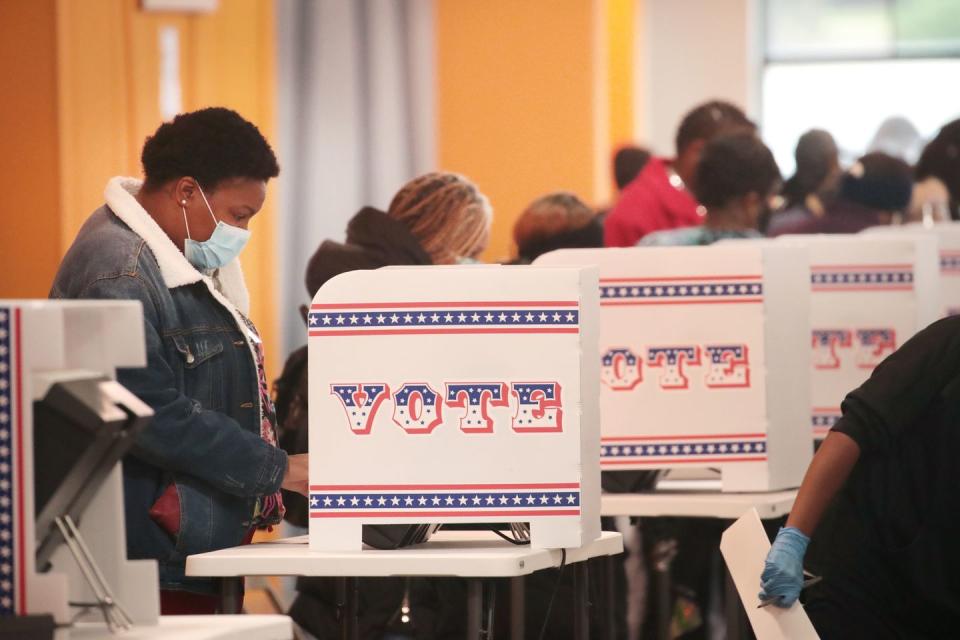

With just days to go until November 3, calls to vote—some aimed squarely at Black women—have reached a fever pitch. But as many electoral strategists know, Black women are among the United States' most consistent voters. Over the summer, as the country celebrated the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment, a reckoning over systemic racism was taking hold. And yet few commemorations directly addressed just how key white supremacy was to many white suffragettes’ arguments for the right to vote. Before the 14th amendment guaranteeing citizenship to freed slaves was passed, many white women argued that they should be able to vote before Black men. Post-Reconstruction, they lamented not having the same rights as Black men. Noticeably, Black women were absent from both arguments. This erasure continues today, in many conversations around anti-Blackness when, inevitably, a white woman will cry “Don’t forget women!” as if there are not women who are Black.

Likewise, the stories of Black women suffragettes have been nearly forgotten. Those that are remembered are often flattened, ignoring the very real complications of power, race, and gender these women contended with. With that in mind, as we careen toward the end of an election season rife with reports of voter suppression but rich with history-making moments, novelist Kaitlyn Greenidge (with the help of her sister, historian Kerri Greenidge) provides a poignant glimpse inside the fight for Black women’s suffrage. Through imagined, though meticulously researched, vignettes, the Greenidge sisters shine a spotlight on three Black suffragettes whose work encompassed more than the ballot box—and whose work inspired a certain Democratic Vice Presidential candidate. Their stories aren’t so easy. They have no clear resolution. They feel a bit messy. But these pieces of history might help us make sense of our similarly complicated present.

ADELLA HUNT LOGAN was born in 1863. Her mother, Mariah Hunt, was a free woman of Black, white, and Indigenous heritage. Her father, Henry Hunt, was a white plantation owner. Adella’s father paid for her education—she attended Atlanta University (a historically Black university that consolidated with Clark College in 1988 to form Clark Atlanta University), and ended up teaching at Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute. She married a fellow teacher, Warren Logan, who was also of mixed-race. Over a nearly 20-year period, from 1890-1909, Hunt Logan gave birth to nine children, while also earning a master’s degree and teaching at Tuskegee. After hearing Susan B. Anthony speak, Hunt Logan became devoted to the suffragist cause. Of Hunt Logan, Susan B. Anthony would later say “I cannot have speak for us a woman who has even a ten-thousandth portion of African blood who would be an inferior orator in matter or manner, because it would so mitigate against our cause…Let your Miss Logan wait till she is more cultivated, better educated, and better prepared and can do our mission and her own race the greatest credit.”

When she sat down to write, perhaps the table was covered in flies. Flies are everywhere in the country. We don’t think of them much today, but they were a part of daily life then. Perhaps on the table were the leftovers from the night before and the pots of butter necessary to feed all those children.

She wrote I am working with women who are slow to believe that they will get help from the ballot, but someday I hope to see my daughter vote right here in the South.

She wrote If we are citizens, why not treat us as such on questions of law and governance where women are now classed with minors and idiots?

She wrote Good women try always to do good housekeeping...Inspectors owe their positions to politics. Who, then, is so well informed as to how these inspectors perform their duties as the women who live in inspected districts and inspected houses?

Perhaps, as she wrote, she had to bat the flies away and pretend she did not hear the youngest baby crying. Or perhaps she was as good as her word, a good housekeeper even under duress, and cleared the table first thing that day.

Maybe she wrote in the family privy. Maybe she wrote as she walked to teach classes, as she drove the wagon to town. Maybe she wrote after the children had gone to bed. Maybe, when the house was quiet at night, she raised up on one elbow and watched her husband sleeping. She didn’t wonder what he dreamed about. She didn’t want to know. Her husband, who it was known, looked for something with other women, even as they worked side by side at Tuskeegee, even as she became the school librarian and he the treasurer, even as the college preached the gospel of the respectable Negro family, her husband would seek other’s beds. Many tried to convince her that men could adequately represent their wives at the polls. But what about women without spouses? she wrote. What about women with callous husbands who patronize gambling dens and brothels? The wives who stay home to cry, to swear, or to suicide?

In the morning she brushed her hair. What was it that her white friend told Susan B. Anthony, her hero, about her? Her hair is as straight as yours or mine and she looks white but must call herself colored. Adella rolls her hair up up up and pins it there. She does this every morning. Maybe some think it is for vanity. Maybe it is. It is also camouflage, which she confused, in her younger days, with survival. When her hair is pinned and her fine dress is on, she can ride in the "whites only" sections of the train. She can stop in ladies’ tea rooms. She can buy a ticket and sit in a segregated lecture hall in Atlanta and hear Susan B. Anthony call for a woman’s right to the ballot. She can have her heart moved.

She was raised to believe that all of this would save her. She believed in the power of education. Education helped her befriend great men. Men like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois. She was one of the first women to earn a master’s degree from Atlanta University. She believed in the dream of uplift. But the dream couldn’t save her. It didn’t keep the humiliations of her husband at bay. It did not stop her career from becoming a casualty of a feud between two men—when DuBois broke with Washington, he declined to publish her essays. She lost her platform, her voice for suffrage. And, then, all those great men she befriended and worked for and kept books for and found sources for—not a one of them would stand with her, publicly, when she called for the right to vote for Negro women. Not a one of them would raise their voices and join the cry.

After all that, one of those mornings, after writing and setting her hair, she went to her husband’s office on campus and set it on fire. Maybe she held a strip of paper to a coal stove or maybe she hid the match in her hair, but she set all the books alight—a sacrilege, in the religion of knowledge. Was her greatest regret that it didn’t completely burn? Was the first thing she asked after being taken to the asylum, Did it burn?

Maybe she took the same route each day to the college. Surely, she walked past the building many times. Times when she was happy, when she was hopeful, when she was overjoyed. It was part of the architecture of her life, of her inner life—her understanding of herself, wrapped up in that place of Tuskegee. So when its founder, her old friend, Booker T. Washington, to whom she still knew she owed so much, passed, she did not know what this place was without him. By then, it was 1915. She had lived to see the Black vote written out of the Mississippi constitution and violently repressed in Alabama. She had lived to see the worst of white folks. And then Washington was gone, and she was left in this place he had dreamed of, and she had dedicated her life to build, with her husband who cared little for her if at all. She looked at what she thought her life would unfold. And she made the decision to jump from the top floor of that campus building because she was not sure what this new world could hold for her. She was not sure if it could see her, if it ever did.

When she first took on the fight, she knew it was an old one. But still, she had hope. In her own lifetime, she had seen changes. She had been born in a world on the cusp between slave and free. She had seen what could happen so quickly for Negro people. Surely, change could come again.

JANIE PORTER BARRETT was born in 1865 in Athens, Georgia. Her mother, Julia, was a formerly enslaved woman. Her father was unknown, though believed to be white because Barrett was of light enough appearance to pass as such. Barrett and her mother initially lived with the Skinners, a white family who hired Julia as a housekeeper. The family educated Janie alongside their own children, and Mrs. Skinner expressed a desire to acquire legal guardianship of Janie so that she could send her North to be educated and pass as white. Julia refused and sent Janie to the Hampton Institute, a renowned Black vocational school that was also a seat of Black organizing and power. There, Janie trained to become a teacher. She wanted to educate Black children and was indoctrinated into the mantra of uplift that so often defined an educated Black woman’s political life. She married the Hampton Institute’s bookkeeper, Harris Barrett, in 1889, and together they had four children. In 1915, she established The Virginia Industrial School for Colored Girls. Seven years prior, Janie organized the Virginia State Federation of the Colored Women’s Clubs—an organized wing of Black women suffragettes. White women suffragettes in Virginia, organized under the Equal Suffrage League, explicitly denounced their efforts. Janie was the federation’s president until 1932.

Love god, love country, love yourself. Make your bed every morning, sheets pulled tight enough to pop a penny. Respect yourself. Sweep the floor each morning and make sure the dust and dirt is to one corner, then sweep that out into the yard. Respect yourself. Wash your face with cold water, wash your hands with cold water, wash the back of your neck and your knees with cold water, water so cold it feels hard on your skin. Don’t shiver. Respect yourself. Respect yourself. Respect yourself. Whenever you sit, make sure you can hold a quarter between your knees. Don’t let it drop. Respect yourself. But also: Follow what a girl needs. She’ll tell you what she needs to be good.

She’d learned these lessons the easy way. The first time she saw the Hampton Institute, with its beautifully turned staircases and dormitories, all designed and built by the boys at the woodworking school, it was as if the whole world was finally aligned correctly, in harmony. It was also the first time she had been around only Negroes. Mrs. Skinner used to say, “But Janie, you’re almost not a Negro,” and she’d been unsure what to do, because she saw the love in Mrs. Skinner’s eyes when she said it, and she saw the disgust in her own mother’s eyes when she overheard it. Mama insisted on Hampton. “But she could pass for white. She is almost white. She could have a better life as white,” Mrs. Skinner tried to say. Mama said, stiff and clear, “She will have as good a life as a Negro.” Hampton Institute was beyond Mrs. Skinner’s imagination. She’d told Janie before she left, “You’ll never sleep anywhere as fine as my house,” and perhaps that was true, but Hampton was the most correct, the most orderly place she’d ever seen, and that was even better.

She found her life’s work. To bring this order to every other Negro. She believed, truly believed, that order was the answer: “It will save us,” she whispered. It was never clearer than when she heard about the girl. Eight years old and sent to prison. Janie read about it in the paper and all that night could only think of that small girl, lost in the wilds of a prison yard, in a uniform too large for her. Lost to disorder. She went herself to the court to argue for the girl to be let into her care. And the judge agreed. A miracle. For her, she built the school. For her, she made the rules. She told the girl’s story to women, Black and white, and the women gave her money to find other wayward children like her and bring them home. She told those women about the order you needed to get the girls straight. She did not tell them the other part—that you listened to them. That you respected them as much as you told them to respect themselves. That making each girl whole was a solitary project, one idiosyncratic to the girl, one you couldn’t discover till you sat with her a bit and listened to her talk and then figured out how you would train her up to greatness.

What was a vote if not a part of that? If not a part of restoring order to the world? If not a part of making the world right? A girl’s life was a promise to a better, different world, and a vote could be, too. If you had it.

MARY CHURCH TERRELL was born in Memphis in 1863 to freed slaves of mixed racial ancestry. Her father, Robert Reed Church, was one of the first Black millionaires, and her mother, Louisa Ayres, owned a hair salon. Mary, like her parents, was white passing, and she grew up amongst enormous privilege. Mary's mother encouraged her to pursue her education, and she was educated at Oberlin College, where she majored in Classics. She was one of the first Black women to earn a college degree and was invited by Oberlin to teach, an early honor, though she declined. She opted to teach in the Washington D.C. public schools instead, and was the first Black woman appointed to a major city’s school board. She founded the Colored Women’s League, which later merged with the National Federation of Afro-American Women to form the influential National Association of Colored Women, of which she was the first president. NACW was an advocacy group for Black women around education, lynching, Black women’s advancement, and suffrage. Unlike other Black women suffragettes, Terrell reported a close relationship with white women suffragists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton—a closeness that probably came from her ability to pass as white.

Her mother had looked up and around in 1863 and concluded that things could only get worse. Perhaps she could dream the future: Reconstruction underway, the white people killing more and more of us every day, and the government doing nothing. So before they could even get there, her mother tried to end it all. When Mary thinks of the women she knows, the women who work alongside her planning and plotting for a better world, she tries to avoid the unsteady ones, the ones who burn a bit too bright. They are always drawn to the fight as much as the solid ones. Would Mary be steady or a flash? She worked so hard to not be a flash.

Mary’s mother left her two legacies. The falling apart and the building up. Before she looked at the bloody calculus of Reconstruction and concluded that it was not worth adding up any more, her mother had done the same with her marriage—she looked at Mary’s father and decided a wayward man wasn’t worth it, even if he was a millionaire, even if he was a colored millionaire. Mary’s mother had had the fortitude to flee to New York and start her own successful salon. She could never reconcile those two parts of her mother—the woman who could have the resolve to flee and the woman who had the clear-eyed despair to decide this world could not be reformed.

Mary was set to prove her wrong. She excelled. The first. The first colored woman on the school board, one of the first two colored women to earn an MA (alongside Anna Julia Cooper), the first colored woman that Susan B. Anthony chuckled with. “We should leave her behind,” she heard her friends say. She knew what Susan said about the others. But. Perhaps to challenge, to ask questions, was to invite in the kind of despair that had nearly destroyed her mother. And Mary couldn’t risk that. She wanted, above all else, to win.

KAMALA HARRIS accepted the Democratic Party’s nomination as Vice President on August 19, 2020. As the first woman of color and first woman of African descent to be nominated to a major party’s presidential ticket, she name-checked Mary Church Terrell and other Black women political leaders in her acceptance speech, acknowledging their commitment to change and their exclusion from voting. She also firmly placed herself in the legacy of uplift that Black women suffragists like Terrell, Hunt Logan, and Barrett built. “(My mother) taught us to keep our family at the center of our world; she also pushed us to see a world beyond ourselves. She taught us to be conscious and compassionate about the struggles of all people. To believe public service is a noble cause, and the fight for justice is a shared responsibility.”

Who whispers in her ear? Is it the bitter defeat of Adella Hunt Logan or the measured love of Janie Porter Barrett? Is it the triumphalism of Mary Church Terrell? Is it all these women? And where in their whispers can she find a space to hear the echoes of history? A history that affords a closeness of power to mixed-race Black women, a power that is as elusive and often stirs up as much resentment as it does admiration?

Does she guard against despair? Does she find peace in the promise of order? Is that order guided by the desire for power? Is it guided by compassion? Does she recognize the echo of history that draws a connection between the question of who a community decides is a criminal and how they are treated? Does she see what an old question that is for Black women in this country, one intertwined with the question of whose voice matters enough to vote?

Voting is important, yes, but it does not put an end to the system of United States democracy that was set up, explicitly, to devalue and destroy Black women’s lives. Our way out will be made up of many different acts, large and small. Whispered prayers, songs sung loud, chants in the street, and speaking into existence a world more abundant than anyone else could have imagined.

You Might Also Like