Rosetta: beginning of the end for Europe's comet craft

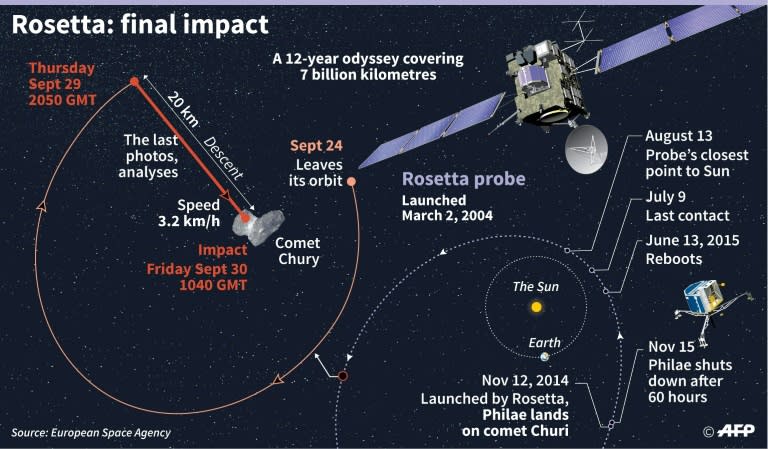

Europe was poised Thursday to crashland its Rosetta spacecraft on a comet it has stalked for over two years, joining robot lander Philae on the cosmic wanderer's icy surface in a final suicide mission. A 12-year odyssey to probe the origins of our Solar System will conclude with a last-gasp spurt of science-gathering after Rosetta is instructed at 2050 GMT to quit the orbit of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The space explorer will descend over a leisurely 14 hours, from an altitude of 19 kilometres (12-miles), sniffing the comet's gassy coma, or halo, measuring its temperature and gravity, and taking pictures from closer than ever before. "It's all go," Rosetta project scientist Matt Taylor told AFP at the European Space Agency's mission control centre in Darmstadt. "We're all very excited. In the final descent, we will get into a region that we have never sampled before. We've never been below two kilometres, and that region is where the coma, the comet atmosphere, becomes alive, it's where it goes from being an ice to a gas." Rosetta will receive the command to crash at a distance of 720 million kilometres (450 million miles) from Earth, with the comet zipping through space at a speed of over 14 kilometres (nine miles) per second. A "controlled impact" at human walking speed, about 90 cm (35 inches) per second, is scheduled for 1040 GMT on Friday -- give or take 20 minutes. Confirmation of the mission's end is expected in Darmstadt some 40 minutes later, when Rosetta's delayed signal vanishes from ground controllers' computer screens. "It's mixed emotions," Taylor said of the impending end. While it will all be over for mission controllers, scientists will be analysing the information gleaned for "years if not decades" to come. - Puzzle pieces - "We've only just started to get an understanding of what the data is telling us, putting together the pieces of the puzzle," said Taylor. "We've got this massive puzzle, all the pieces are everywhere, and we need to put them together." The first-ever mission to orbit and land on a comet was approved in 1993 to explore the origins and evolution of our Solar System -- of which comets are thought to contain primordial material preserved in a dark space deep freeze. Rosetta and lander probe Philae travelled more than six billion kilometres (3.7 billion miles) over 10 years to reach 67P in August 2014. Philae was launched to the comet surface in November of that year, bouncing several times, then gathering 60 hours of on-site data which it sent home before entering standby mode. Insights gleaned from the 1.4-billion-euro ($1.5-billion) mission have shown that comets crashing into an early Earth may well have brought amino acids, the building blocks of life. Comets of 67P's type, however, certainly did not bring water, scientists have concluded. Rosetta's comet is currently speeding away from the Sun on its near seven-year elongated orbit, which means the craft's solar panels are catching fewer battery-replenishing rays. Rather than just letting it fade away, scientists opted to end the mission on a high by taking measures from distances too close to risk under usual operating conditions. Rosetta was never designed to land. "Tonight is the beginning of the end," said Taylor. "That is what we're waiting for -- we're waiting for this manoeuvre to begin that final phase." A highlight of the final hours will be a one-off chance to peer into mysterious pits dotting the landscape for hints as to what the comet's interior might look like. Rosetta was programmed to switch off on impact, to make sure its signals do not interfere with any future space missions. "After Rosetta has touched down, it will not be possible to collect or return any additional data," the ESA said.