Russian rejection of ICC mirrors US stance

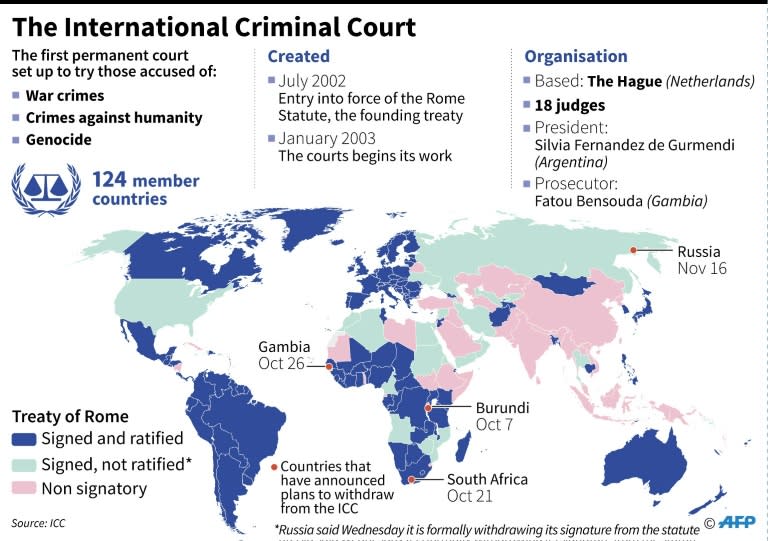

The United States expressed regret Wednesday that Russia had withdrawn from the International Criminal Court -- 14 years after Washington made exactly the same decision. While Washington accuses Russian forces of brutal crimes in Syria and Ukraine, it does not accept the jurisdiction of the court over its own personnel. Like Russia, the United States signed the Rome Statute of July 17, 1998, but neither country ever ratified it and now both have definitively rejected its authority. Russia's decision was seen by many as the latest step in a trend that may threaten the future of world justice, after a string of African countries pulled out from the court. "Obviously we recognize these are decisions that ultimately are sovereign national decisions to make," US State Department spokesman John Kirby said. "But that doesn't -- even though we're not a signatory -- diminish our belief that the court does provide a valuable framework." The United States withdrew from the Rome Statute in May 2002, in a letter to UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan from US under secretary of state John Bolton. At the time, president George W. Bush had just launched a global war on terror and invaded Afghanistan in response to the September 11 attacks. On Tuesday, ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda said she is considering launching a full investigation into reports that US CIA operatives tortured captive suspects. That they did is in little doubt. US investigations concluded that the Bush administration's "enhanced interrogation techniques" were unlawful. Bush's successor, President Barack Obama banned the harsh techniques and in August 2014 admitted candidly: "We tortured some folks." So an ICC war crimes investigation would have a lot of evidence to work with, but no one expects the world's only superpower to surrender its troops and spies. "We have a robust national system of investigation and accountability that is as good as any country in the world," a State Department spokeswoman said Tuesday. Washington will, however, support "ICC prosecution of those cases that advance US interests," Kirby said. Russia stands accused of greater, and more recent, crimes: The deliberate targeting of civilian hospitals and clinics in its air war against Syrian rebels. Just hours before Moscow announced it was pulling out of the court, the State Department said its recent air strikes were a "violation of international law." But if this were proven, where would international prosecutors bring a case if not the ICC? "Russia's announcement that it would not join the International Criminal Court is far from big news for the court," said Elizabeth Evenson of Human Rights Watch. "Although it signed the ICC treaty, Russia never ratified it and thus was never a member," she explained. "The announcement says much more about Russia's retreat from international justice and institutions and is part of the larger harm being inflicted on its own people." - No friend of the court - But has Washington, accused of crimes of its own and no longer a signatory to the ICC treaty, lost some of its credibility when accusing rivals like Russia? "That's a completely fair point," said Philippe Bolopion, Human Rights Watch's deputy director for global advocacy. "Of course, not to have to signed the treaty doesn't mean that the US is doing the same kind of things that the Russians are doing in Syria. "I wouldn't draw any equivalence there," he cautioned. But he added: "The US has never been a friend of the International Criminal Court. During the Bush years they were going around the world trying to undermine it." Obama's administration has at least not sought to weaken the court further. But he decided not to prosecute the Bush-era officials who ordered detainee abuse, and the administration argues that the ICC probe is "unwarranted." And now, America has chosen a new president. From January 20, populist maverick Donald Trump -- who declared on the campaign trail that "torture works" -- will have all the war on terror powers of his predecessors.