Shirley Manson on Garbage at 25: ‘I didn’t think of myself as a singer’

Shirley Manson thinks back to the summer she became a star and shudders. As frontwoman of Garbage, the flame-haired Scot seemed perfect for the job of rock celebrity: she was striking, formidable and smart. But the musician reflects on her band’s early days with fresh clarity. “It was very challenging,” she recalls from her home in Los Angeles, of the time she joined the band and changed the course of rock music forever. “I keep expecting that my feelings about that period are going to change with time. But they haven’t.”

“The more time passes,” she continues, “the more I realise how much stress I was under. I wasn’t really aware of it at the time other than that I felt uncomfortable. Now, with the passing of 25 years, I realise I was really under immense strain.”

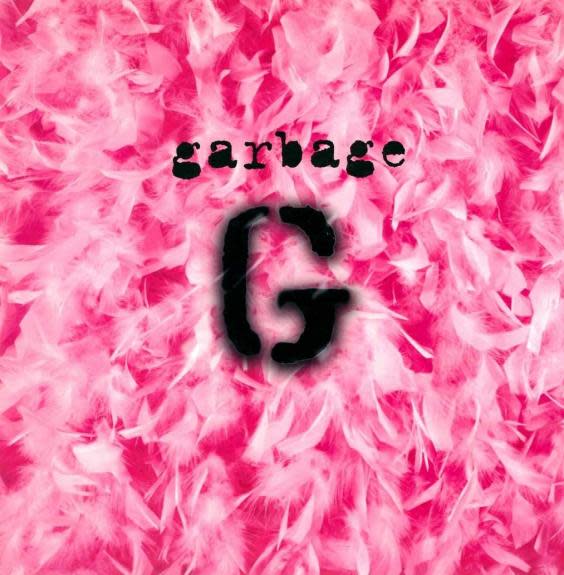

We are talking because, this month, Garbage’s debut self-titled album celebrates its quarter-century as a modern classic. It was unleashed on 15 August 1995 on an alternative rock scene heading into stormy waters. Grunge was in its death throes. Nirvana were over. Their drummer, Dave Grohl, went on to form Foo Fighters, who turned out to have more in common with Deep Purple than Dinosaur Jr. Nu metal – Satan’s own genre – was on the horizon.

And then in swept Garbage, led by Manson and Nevermind producer Butch Vig. Their debut album materialised as an effervescent one-two punch – an irresistible collection of hits-in-waiting, blending grunge, trip-hop, goth and industrial rock, and headed by a cool-as-hell singer from Scotland. Garbage married rock and pop in a way that hadn’t been done before and was an exhilarating listen. It was impetuous, glamorous and sold like hot cakes, peaking at six in the UK charts and going top 20 in America.

But despite all its attitude, the album had its vulnerable moments, too. In the cracks of songs such as “Vow” and “Stupid Girl”, amid the glam-grunge guitars and Manson’s imperious vocals, lurked flickerings of doubt and fragility. It added up to an irresistible mix of sweeping highs and lows, one that launched Garbage into a career that, a hiatus from 2005 to 2010 aside, has endured through the decades (they are currently working on a seventh album).

For Vig, it was a chance to invigorate his sound. “After Nirvana, I had gotten tired of getting calls to do the grunge production,” he says now, also over the phone from Los Angeles. It was no surprise that record labels were seeking out his Midas touch. As producer of Nevermind and the Smashing Pumpkins’ Siamese Dream, he was one of the chief architects of the grunge sound, which blended the pummelling force of heavy metal with the nimble melodies of indie. “Production-wise, I wanted to try something different,” he says. “For me, that was what was fresh about Garbage. It had guitars, it had lots of elements of hip-hop, electronic, trip-hop, orchestral bits.” And it sounded like little else in the charts at the time.

The story of Garbage’s mid-Nineties rise is the stuff of rock folklore. It began with Steve Marker, future Garbage guitarist and hometown buddy of Vig, watching MTV show 120 Minutes late one night. There, he saw Edinburgh-native Manson performing the song “Suffocate Me” with the group Angelfish, a short-lived off-shoot of her previous band, Goodbye Mr Mackenzie.

He was impressed with her vocals and seemingly effortless charisma. Phone calls were made.

Dazzled by Angelfish, Vig, Marker and guitarist Duke Erikson had arranged to meet Manson in swanky London hotel the Landmark on 8 April 1994. Manson had been on and off the dole during Goodbye Mr Mackenzie and was stunned to discover coffee at the Landmark priced at a scandalous £1.50.

Everyone appeared to get on. But tragedy was on the horizon.

“Later that evening, I was going out for dinner with producers and engineers who I knew in London,” says Vig. “I sat down at the table. And they were like, ‘Did you hear the news? Kurt died.’ I freaked out. I went into shock and said, ‘Guys, I gotta go.’ I got up and went back to the hotel and took the first flight back to the US.

After the shock of Cobain’s suicide had abated somewhat, it was arranged for Manson to fly out for a more official audition in Wisconsin – but it was not the slick experience she was expecting. “I thought, ‘This is going to be really professional and organised,’” she recalls. “It’s not going to be this riotous chaos that I was familiar with from Goodbye Mr Mackenzie. It was nothing like that. They were really untogether. They literally stuck a mic in front of me and said, ‘OK… we’re going to play you some songs we’ve written.’ It was an unmitigated fiasco.

Despite the rocky start, the band started making headway. Or at least so Vig, Erikson and Marker felt. They encouraged Manson to reconfigure and add lyrics to tracks already in a protean state. These included future smashes “Stupid Girl” and “Queer”.

But at the time, Manson was unsure she could carry it off. She presented the band with a new song, “Milk”, which she essentially wrote from scratch. It would go on to become one of the album’s biggest hits, although she says now that she took little satisfaction from the accomplishment. She was still struggling to think of herself as a front person. “They loved my voice. I had no sense of myself as a singer. I didn’t think of myself as a singer.”

It’s surprising to hear Manson talk this way, but at the time it was a huge change. At school in Edinburgh, she had been bullied for her pale features and bright red hair. She coped by immersing herself in the local rock scene and, at 16, dropped out and joined Goodbye Mr Mackenzie. She would spend the next decade singing backing vocals and playing keyboards in the group, whose earnest jangle pop had a loyal but modest following.

With Garbage, she was thrust into the limelight and not entirely comfortable with her newfound position as rock poster-woman. She didn’t feel she deserved the attention. “I’ve suffered imposter syndrome my whole life,” says Manson now. “I had been in Goodbye Mr Mackenzie for 10 years before I joined Garbage. I was quite happy in the background. People think of me now as some sort of ambitious go-getter. That’s not who I was.”

Suddenly she was halfway across the world, living out of a hotel in Vig’s hometown of Madison and trusting her artistic future to three men she barely knew and a good decade older. And Vig was risking a great deal, too. Vig’s Smart Studio in Wisconsin had become an epicentre of the American alternative scene since he opened it in 1983. It was at Smart that Nirvana recorded “Polly” – with Vig in the production booth – and where Smashing Pumpkins laid down their 1991 debut, Gish.

When Vig started Garbage, several music industry friends took him aside and told him he was crazy, that the band was doomed to fail and then his reputation as a super-producer would go down in flames. But Vig was convinced that his new path was the right one.

“After the success of Nirvana and the Smashing Pumpkins I had a lot of offers to move to Los Angeles or New York or London to set up a studio,” he shrugs. “All these high-powered managers were calling: ‘You’re going to work with the Rolling Stones, you’re going to work with Pearl Jam.’ I didn’t want to do that. I didn’t take on a manager. I stayed in Madison. I liked being off the beaten track. I felt it kept me grounded.”

Garbage hit stores in August 1995 and was a sensation. The commercial crescendo came with “Stupid Girl”, built on a sample of The Clash’s “Train In Vain”, which became a ubiquitous hit in the UK in the summer of 1996. And yet, even as the confetti rained down, Manson felt ever more adrift. “I didn’t let myself enjoy it for numerous reasons,” she says.

“I felt pretty worthless as a human being. I had a lot of guilt. I came from a music scene [in Edinburgh] that was rife with unbelievable talent. And here I was on Top of the Pops. Who was I to stand front of the stage on Top of the Pops, this iconic TV show? I didn’t have half the talent of so many of my peers at home. I was embarrassed.”

And then came the misogyny. “It’s funny,” she begins. “On the one hand, [Garbage] was one of the most exciting things that ever happened to me. But also, it was the most lonely, most cruel. I endured so much criticism. When I look at the headlines from magazines, I am shocked at the venom and the disrespect that I was under and how much worshipping there was of my male colleagues.”

Rolling Stone described Manson as a “pop-star-as-one-night-stand”; Entertainment Weekly praised her “menacing sexuality”. This sort of language was rife in the music press of the time. “They asked if I was a prostitute,” remembers Manson. “They asked me all kinds of things about my body, my sexual preferences, my face, how my lips looked good. It was truly, truly unbelievable. Now I look back and think, ‘Wow… I must have really been threatening to these boys.’ And they were young boys, a lot of the journalists writing for these papers I loved.”

By that point, Manson and her bandmates were unstoppable. Garbage went on to shift a blockbusting 4 million copies worldwide and, in 1997, receive three Grammy nominations (one for best newcomer and two for “Stupid Girl”). Manson clearly found the experience stressful, but she is proud of what the group achieved and its legacy, of proving pop and heavy rock could co-exist in beautiful harmony.

“If there was more than one of me in the band, it would have been a disaster,” she says. “If they hadn’t had me, it would have been a disaster. I didn’t think anybody in their right mind would listen to that first record. Shows you what I know.”