How My Son Became The Inspiration For A Groundbreaking New Disney Character

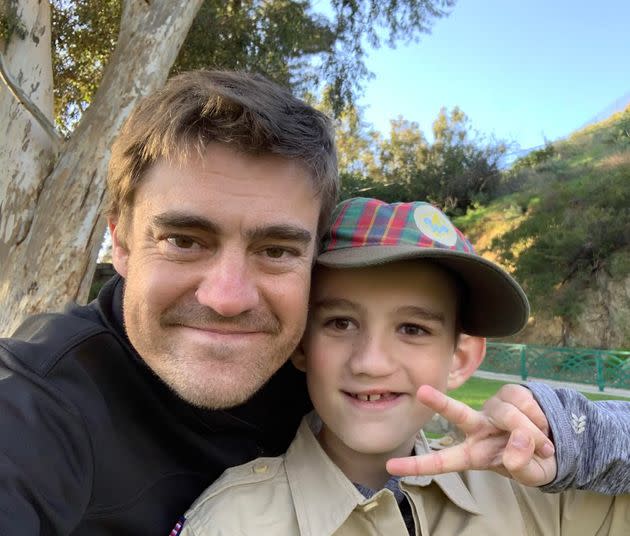

The author and his son at a Cub Scouts ceremony.

Eleven years ago, my wife was in a parking lot with our newborn, packing their stuff into the trunk of our car, when an elderly man approached. He thrust a finger at our infant, who was born with a unilateral cleft lip and a bilateral cleft palate (which our doctor would describe as “extremely wide” on a medical form), and glared at my wife. He scolded her. Though he didn’t use these words exactly, his meaning was clear: What mistakes had my wife made to do this to her baby?

What this man didn’t know ― and what many may not know ― is that my wife did nothing wrong to cause our son’s condition. We don’t know why some kids are born with cleft lips and palates, but we do know that about 1 in 700 babies are affected globally. The stigma persists, however, despite it being one of the most common birth defects in the U.S.

Our son has had multiple surgeries to address his palate and cleft, and there are more to come. These procedures have left him with a small scar above his lip. But what I want to stress here is what I stress to him: There’s nothing wrong with him. He has a condition that requires surgery, but he’s a perfectly healthy boy. He isn’t alone. This is what compels me to write this article — to help expand our vision of authentic representation to include those with facial difference.

There’s a sea change happening, and Hollywood has been energized to focus on D&I — diversity and inclusion — to portray with authenticity the prism of cultures, ethnicities, genders, preferences and abilities. I would like to see facial difference reflected there too. Often, facial differences are a design trope ― a signifier for villainy. If you see someone on screen with a scar across their face, they’re bad news.

I’m a writer, and I’ve had the good fortune to write on Disney Junior’s “Firebuds,” about kid first responders and their first responder vehicles. Since my son was born, his condition, his positive attitude and his experiences have shown me the value of telling stories with people and characters like him. So, it wasn’t long before I pitched a story featuring a kid car with a “cleft hood.”

When the time came to cast Castor, the car with the cleft, I felt it was important for him to be voiced by a child who actually had a cleft. Naturally, I thought of my son. He’s a terrific young actor, I think, but he also sounds right for the part. Kids with a cleft often have difficulty pronouncing certain sounds, and many of them have years of speech therapy.

I couldn’t be more proud of him and how the episode came out. Working with my son to help tell his story has been a highlight of my career. Of my life. “Cleft Hood” is not about clefts, per se. Rather, it is a story about considering the feelings and experiences of others. Using empathy is vital, not just in how we comport ourselves as humans, but in how we represent people in film and television. My hope was to depict someone with a facial difference who was adorable, fun, well liked and living a full life. Castor has an extra challenge, but he is just like other kids.

Of course, any character can have facial difference. But this doesn’t have to connote villainy. Such qualities could just as easily suggest somebody is strong, brave, determined, cherished and empathetic. Like in the real world, a scar could mean someone can talk or breathe easier, or had a lifesaving procedure. Maybe the condition gave this character a brighter outlook on life. Maybe they’re resilient and loving not despite their differences, or not even necessarily because of them, but because these qualities are within reach of any human.

Though my son’s lip was technically “repaired,” he didn’t need “fixing.” I wish I could tell that man in the parking lot that my son (and his mother) need love, not condemnation. As writers and creators, and as people participating in society, we can make room for facial difference representation. We can let the 1 in 700 kids feel seen, and we can help the other 699 see that their friend ― the one with a small scar on his lip ― has just as much to offer this world as they do.

Jeremy Shipp is a writer on “Firebuds.” Previously, Shipp was part of the Emmy-winning writing team on Disney Channel’s “Rapunzel’s Tangled Adventure.” With over a decade of experience as a writer for animation, his additional credits include “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,” “Family Tools” and “Dinotrux.”