Starling Bank’s Anne Boden: ‘We’ve always had a model that was going to be profitable’

Could coronavirus kill online-only banks? That was a surprising question posed by City analysts this summer as they argued the pandemic could have counterintuitively cemented the position of the big players during lockdown.

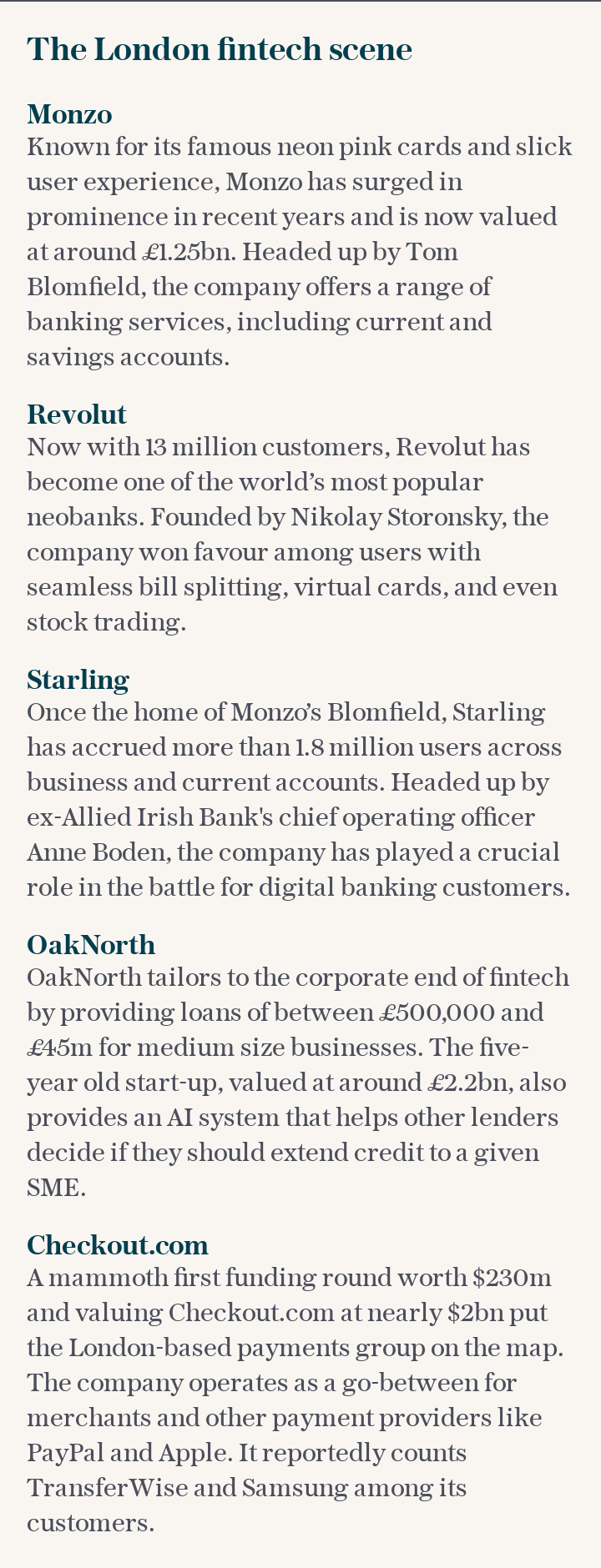

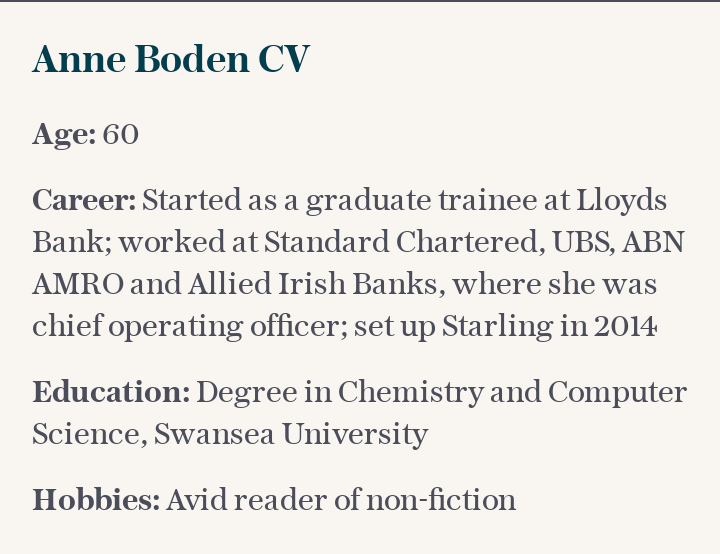

Instead of challenging the high street banks, Britain’s financial technology stars Monzo, Starling and Revolut are still yet to make a penny. But 60-year-old banking veteran Anne Boden, who founded Starling in 2014 after 30 years working for “boring big banks”, is determined to change that this year.

“In December, we will be monthly profitable,” the former computer scientist vows, although she won’t be drawn into when the bank might turn an annual profit.

“We’ve always had a business model that was going to be profitable. Some of these other banks that launched from 2014 thought they could be Amazon and make losses for the foreseeable future. But the Bank of England really wants banks to be profitable within five years.”

Threadneedle Street has clearly started to lose patience with some of the banking industry’s newcomers. Over the summer, its supervisory arm the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) said that many new banks had “underestimated the development required” to become successful and now needed to focus on making a profit. Its message came after losses at Revolut more than tripled to £106.5m in 2019, while Monzo’s rose from £47.1m to £113.8m, and Starling’s doubled to £52m.

Boden, who reads several business books a week, has not lowered her ambitious growth plans during the pandemic and this week will find out if the bank has been awarded £35m in funding to encourage competition in banking. While she has accused her rivals of “swimming naked” without a route to profitability, the Welsh entrepreneur’s end game has always been for digital-only Starling to compete against FTSE 100 giant Barclays, an ambitious goal she’s well aware can only be achieved by making money.

“If you look at why we’re going to make a profit [before others], there’s a couple of things going on. A lot of the others make a lot of money on international travel and we’re far more domestic payment based. We’re less impacted by international travel. Secondly, our customers are not necessarily spending on Starbucks or Pret; they’re much more likely to be spending at Sainsbury’s or Tesco,” she says.

“Our customers are older and tend to use us as a real account. What we’ve done is build a customer base that is far more profitable. We have just launched kids cards, and our customers have kids. It’s paying off.”

The intense competition in the online banking sector and the bitter rivalry between Monzo and Starling is widely known in the fintech industry. Monzo’s founder and former chief executive Tom Blomfield led a walkout of key Starling executives in 2015, just before launching Monzo. For 18 months, the two companies were based on either side of a small street off Finsbury Square in London.

With the competition so close, Starling decided to frost all of its windows. “It’s true,” says Boden, laughing. “But now they’ve moved up the road”.

The competitiveness is not surprising given that the potential rewards are huge. Coronavirus has accelerated the shift away from branches and towards online banking and Boden says this could create opportunities. “Trying to find things for branches to do is a bad idea,” she says, addressing a problem facing the high street lenders she’s trying to compete with.

“The banks need to get together to share branches. You don’t need a branch from every bank in every town. People are not using debit cards; they’re using mobile wallets. We did really well on new account opening during lockdown as people didn’t go into a branch”.

Bank bosses have long been trying to grapple with this shift in behaviour. Senior executives from taxpayer-backed lender NatWest Group approached Monzo for informal talks about a takeover around three years ago, highlighting how seriously major rivals take the threat posed by these players even before they’ve turned a profit.

After executives baulked at the suggested price tag, they decided to launch their own rival product. The attitude of some inside NatWest at the time was that there were 42 million people in the UK without Monzo, so why give the fintechs a “free run”?

But mimicking the success of these start-ups proved trickier than expected and six months after launching its product, Bó, the bank shut it.

Boden, a veteran of the banking industry who has worked at NatWest, Allied Irish Banks, Lloyds Bank and UBS, has no doubt received similar approaches from the large banks, but has her eye on a future stock market listing instead.

“I’ve always said that I didn’t do this to sell out to a big bank, and I think that’s still true,” she says. “It’s too early [to say for sure]. Now is the exciting stage because profitability will give us an awful lot of options.”

Are investment bankers trying to get work on Starling’s potential float already? “I can’t possibly say,” she adds, laughing. “Everybody wants to talk to us. It’s not us wanting to talk to them.”

But the next few months will also be tough. Coronavirus cases are rising and although no job cuts are on the cards (and no staff have been furloughed) Boden acknowledges that working from home for such a long time could impact employees’ mental health, so has launched a programme called “Never Home Alone”, where staff can socialise with each other through online events such as cooking classes. Boden says she unwinds herself by trawling through fabric books, adding that perhaps she should have been a designer.

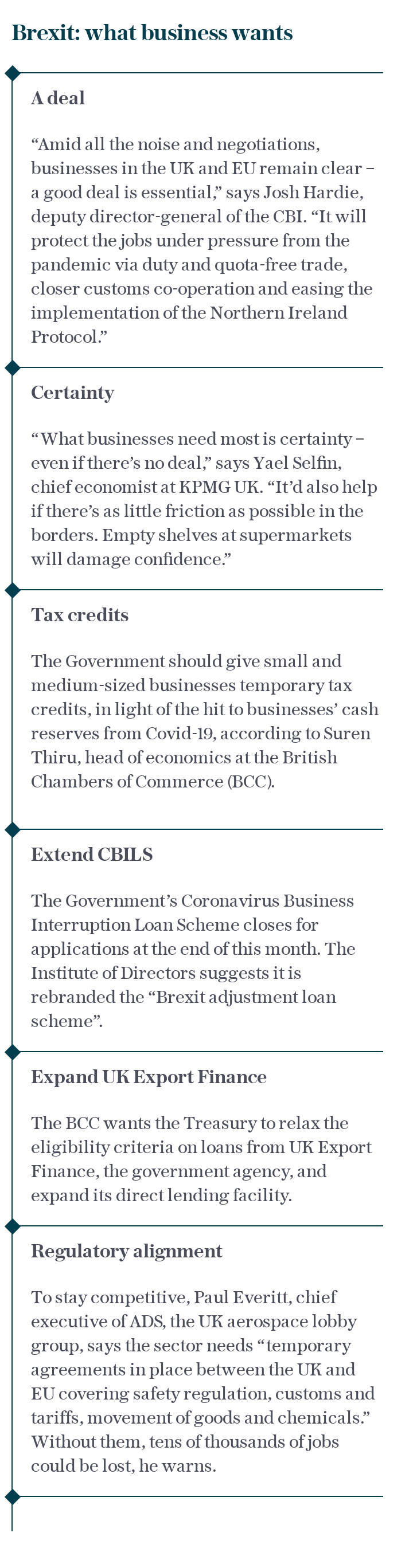

As well as keeping morale up during what could be a very difficult winter, Starling is also facing the same headwinds as the rest of the industry. It is among the banks that have been offering Government-backed coronavirus loans to small businesses, including the Treasury’s hugely popular Bounce Back Loan Scheme. At some point the sector will be tasked with chasing these debts.

“Collecting [the money] is going to be difficult and we’re expecting a substantial amount of defaults. At the momen,t UK Finance is working with the Treasury and the British Business Bank on all the processes to collect those loans,” Boden says. “Everybody is concerned about the reputational damage on this sector when we have to start collecting these loans, but everybody realises this has to be done carefully.”

Boden’s CV has also got longer this year. She is now on the board of UK Finance, the trade lobby group, and was appointed to the Government’s new post-Brexit board of trade earlier this month.

UK Finance is currently looking for a new chief executive after its former boss Stephen Jones quit over sexist comments he allegedly made while at Barclays during the 2008 financial crisis and Boden thinks it’s important that women make it onto the final shortlist. Although the banking industry is still male-dominated, more women are taking leadership roles. Boden says there are many top female executives with experience of “actually getting things done”.

“You’ve got a situation where they weren’t at the sharp end during the financial crisis, but they were cleaning up the mess afterwards. Those women are not going to let it happen again,” she says.

“I have a lot of confidence in a whole cadre of women who will be leading British banks over the next couple of years and I’m proud to be one of them.”