In Syria, governors hope for end to 'exile'

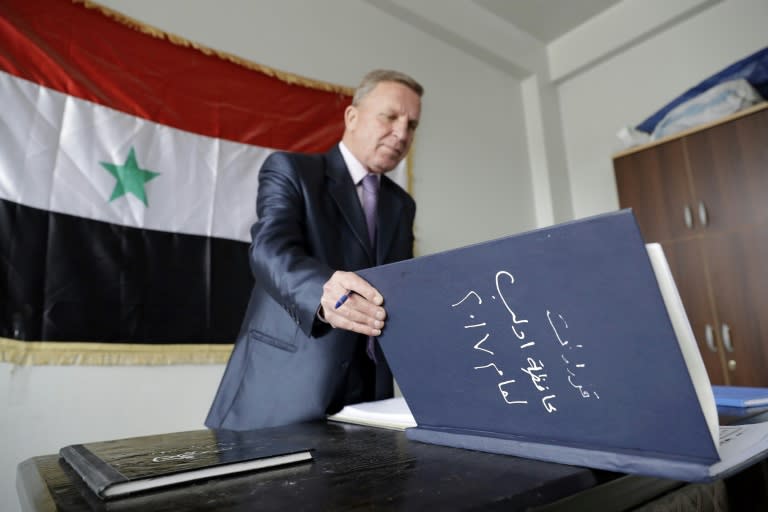

"Welcome to Idlib province!" the Syrian governor proclaims, seated in a converted classroom in Hama city some 90 kilometres (55 miles) from his real office, held by rebels since 2015. With opposition fighters led by Syria's former Al-Qaeda affiliate in control of the province he was appointed to lead last year, Ali Jassem instead works from the second floor of a Hama school. And he's not alone. One floor up is Raqa governor Abed Khaled al-Hamud, 53, seated behind a desk under a photo of President Bashar al-Assad, flanked by the flags of Syria and the ruling Baath party. His province is even further away than neighbouring Idlib, and its provincial capital is still firmly in the grip of the Islamic State group. Despite being installed more than 220 kilometres (135 miles) from Raqa city, Hamud insists he represents "continuity of the state" in his province. Raqa was the first provincial capital to fall from government control after the country's March 2011 uprising. It was captured by rebels in March 2013, but then taken from them by IS jihadists, who made Raqa city their de facto Syrian capital. But the government has continued to pay the salaries of its employees in the province, which is a key responsibility for Hamud. "Even though the state doesn't collect any taxes (there), the salaries of 67,000 government employees or retirees are issued each month for those who are still in Raqa or in other provinces," he tells AFP. The money is kept in Hama until either the employees or a trusted proxy can reach the province from Raqa and take it back with them. - 'We'll return' - Jassem was appointed the governor of Idlib province just a year ago, long after it was captured by rebels, so he has only ever worked out of his second-floor Hama classroom-turned-office. Idlib city became the second provincial capital to fall from government control when it was captured in March 2015 by the Army of Conquest, an alliance led by former Al-Qaeda affiliate Al-Nusra Front, later known as Fateh al-Sham. "We're temporarily in Hama, but we're certain that we'll return to Idlib thanks to the victories of the Syrian army," Jassem says confidently. "All the institutions, the utilities and public administration were transferred here, but it operates independently of the Hama governorate," he adds. The water utilities from Raqa and Idlib have followed their governors, installing themselves in offices at Hama's public water company. The state electricity providers from the two provinces have also taken up residence in Hama's electricity company. But at such a remove, there is little real work they can do. "In Idlib, the public administration is shut and for an identity card or a passport, people have to come here," says Jassem. "It is the world war against Syria that has forced this unprecedented situation on us," he adds. More than 320,000 people have been killed in the nearly six years of Syria's conflict, which has drawn in international players and attracted jihadists like IS. Jassem is also still overseeing the payment of state employee salaries, and says dozens of people a day pass through the offices of his governorate-in-exile. - 'State still functioning' - On the same floor, a group of farmers waits for Mohamad Hmashdo, director of planning for Idlib. "We distribute childhood vaccines, medicine for animals and even small generators for water pumps," he says. While residents of Idlib can travel relatively easily to neighbouring Hama, the situation is more complex for Raqa residents. "Daesh doesn't let anyone leave, unless they are seriously ill," says Hamud, using the Arabic acronym for IS. "So they come clandestinely through the desert." "One time a student who wanted to take his exams left from Raqa on horseback until he reached Aleppo and then took a taxi to Hama to take the exams," he adds. Marriage contracts and birth and death certificates are registered sometimes two or three years late. "Daesh has destroyed all the archives... We must reconstitute them completely. It's a huge job, but it proves that the state is still functioning," Hamud adds. At the end of the corridor, a banner reads "Raqa City Municipal Council." Municipal council head Talal al-Sheikh, 49, was appointed a year ago, and says he ensures that municipal employees who remain in Raqa, of the 740 who once worked there, keep doing their jobs. Communication with the employees is still possible, but is done secretly for their safety. "They clean the city, they collect garbage, drive municipal vehicles, under the supervision of a Daesh emir (commander), but it is the government that pays their salaries," he says.