Teargassed, beaten up, arrested: what freedom of the press looks like in the US right now

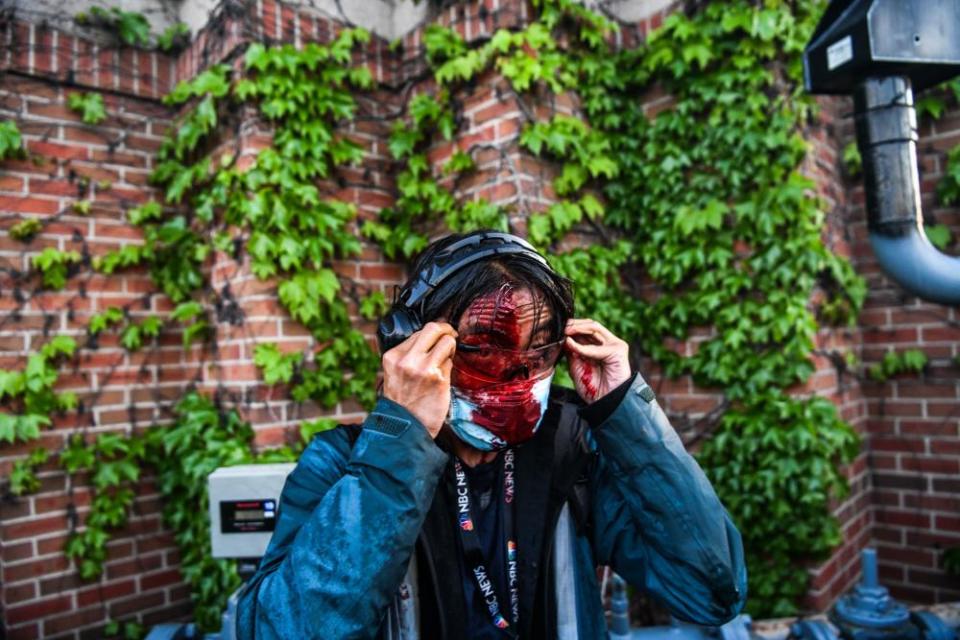

Caught in the middle of a scrum covering protests in Minneapolis on Saturday, photojournalist Ed Ou could feel his hands and face were wet. For a long time, he didn’t know if it was teargas, pepper spray, or blood – in the end, it turned out to be a combination of all three.

Related: 'I’m getting shot': attacks on journalists surge in US protests

Sheltered behind a wall in a pack of journalists, Ou had not seen the attack coming. He has documented civil unrest in the Middle East, Ukraine and Iraq, where he learned a few things: never get in the police’s way, find shelter, stick together and make sure you are clearly identifiable as press. So when the curfew hit and police fired teargas into the crowd of protesters, Ou stood steady, out of the way, documenting. And then the unexpected happened.

“They literally started throwing concussive grenades in our direction, in the middle of the journalists,” he says. The police approached Ou directly and maced him in the face, spraying his camera, too. What ensued was a prolonged attack that involved being hit at with batons, being teargassed, dodging concussive grenades and begging for help.

The account has been corroborated by several other journalists on the ground, including the Los Angeles Times’ Carolyn Cole, who incurred an eye injury, and Molly Hennesy-Fiske, who was shot with rubber bullets several times in the leg. They describe the journalists as having been “completely against the wall, in an alcove, at least 15ft off the road to allow the police line to pass”.

Having covered conflict nationally and internationally for years, each express that whilst they understand the dangers of covering civil unrest, they never expected to be directly attacked by police forces in America. “I have never been shot at by police – even when covering protests overseas and war zones in Afghanistan and Iraq,” says Hennessy-Fiske.

This is what freedom of the press in America has looked like over the past week. As of 9pm Thursday, the US press freedom tracker has received 192 reports of journalists being attacked by police forces while covering the protests across the US.

This weekend, journalists in a group covering the protests in Minneapolis were hit with pepper spray, concussion grenades, batons, and tear gas by Minnesota State Patrol. We had our cameras out, press badges on and were clearly identifiable as media. I ended up with 4 stitches. pic.twitter.com/pR3aoRDco3

— Ed Ou (@edouphoto) June 2, 2020

Among them, some have sustained serious injuries. Linda Tirado, a photojournalist, was hit in the face with a tracer round, resulting in loss of sight in one eye. The Chicago Tribune’s Ryan Fairclough was left with stitches after being shot through the window of his moving car while trying to retreat away from a police blockade. In Detroit, Nicole Hester was hit by pellets fired by Detroit police, leaving welts on her body. Others have been beaten up, arrested, their equipment damaged and they have been threatened for taking photos and filming on public streets.

These are not one-off incidents: this is a picture of widespread attacks on the profession. Whether it is constitutional is already under question – this week, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has filed what is thought to be the first lawsuit accusing a US city of breaking the constitutionally mandated freedom of the press.

Ou has gone back to the incident in Minneapolis several times since Saturday, analysing what he could have done wrong, or what he might do differently next time. But he is left with one conclusion: “The biggest mistake I made was trusting that the police would recognize the fact that we are there to document and remain impartial in that situation.”

‘They will treat you any way they choose’

“When the people start looting, we start shooting,” Donald Trump tweeted as mass unrest unfolded in America following the death of George Floyd.

From that point on, the world knew how America’s political leadership wanted to handle the protests. Since then, the president has called protesters thugs, terrorists and hoodlums. He has deployed the national guard, berated governors for being weak while urging them to “dominate” protesters and suggested 10-year prison sentences for them.

I think the police see journalists as attacking their tribe – they feel they are getting a lot of bad press because of what happened to Floyd

Barbara Davidson

And at several points, he has made clear that the press is to be viewed as part of the problem. Trump has directly accused journalists of being complicit in the destruction taking place during the protests, suggesting they were in cahoots with looters. “If you watch Fake News CNN or MSNDC [sic], you would think that killers, terrorists, arsonists … would be the nicest, kindest most wonderful people in the world,” he said in one tweet. And then, shortly after: “It is almost like they are all working together?”

For journalists working on the ground, a direct line can be traced between the president’s comments about members of the press and the violence inflicted on them.

“When the president declares you an enemy of the state … Well the police, their job is to protect the state, right? So if they view us as the enemy they will treat you any way they choose,” says Pulitzer prize-winning photojournalist Barbara Davidson. “I think the police see journalists as attacking their tribe – they feel they are getting a lot of bad press because of what happened to Floyd and so I think they are retaliating against us,” she adds.

Davidson was attacked on Saturday evening in Los Angeles. After a confrontation with a police officer telling her to move out of the way, she did – then, he came at her from behind and pushed her. She fell to the ground and whacked her head on the curb. As her neck whipped back and she tried to get up, she felt grateful: she had come to the protest wearing protective headgear and goggles.

That cop may have been a bad egg – just as there are looters amongst the mostly peaceful protesters so too there will be rogue cops who use and abuse their power, she says. But when she is out working, Davidson is not worried about the looters, she is worried about police.

Now, the worst part of Davidson’s day while out covering the protests is finding her car. She runs through highly policed neighborhoods with her head down, waving her press pass and shouting to identify herself.

“That is something you do in war zones – it is such a mindfuck. I am in the streets of Los Angeles,” she says.

‘The police understand the power of visuals right now’

Davidson is not the only one arguing that covering those protests, on American soil, has thrown reporters in extremely dangerous circumstances.

When Christopher Mathias was pushed by a cop in New York while covering the protests on Saturday, he made the mistake of telling the officer to fuck off. Within seconds, cops had their legs on Mathias’ head; twisting his arm and putting pressure on him until he thought his arm might break.

Mathias has covered far-right rallies, the Baltimore uprisings and the first Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson in 2014, and he calls the current protests some of the most intense he has seen. In part, he puts that down to the nature of the protests.

In Charlottesville, Virginia, he watched as armed, white far-right protesters pushed back the police with little resistance. In Georgia, he watched as militarized officers policing a neo-Nazi rally targeted anti-racist protesters, threatening them with semi-automatic rifles while white supremacists were left alone.

You have that badge around your neck, and more often than not it’s going to protect you rather than harm you

Christopher Mathias

“There are a lot of Trump supporters in police departments,” says Mathias. He points out the speech made by Trump in Long Island in 2017, when a crowd of officers clapped as he encouraged them to rough people up.

“We are in this fascist moment and it stands to reason that the [police] probably don’t like the press and think that being law enforcement gives them the right to rough up whomever they please,” says Mathias. In other words, while not all officers act this way, now is an opportune moment to hide in plain sight.

Mathias thinks the police probably dealt with him so heavy handedly because he was disrespectful to them, not because he is a journalist. For him, that’s a reminder of what can happen to any person at a protest in the current climate.

“Journalists have privileges that a lot of people don’t. You have that badge around your neck, and more often than not it’s going to protect you rather than harm you. A lot of cops at least have an understanding that if they mess up a journalist it could backfire,” says Mathias.

NYPD violently arresting protestors, journalists. They rushed @DGisSERIOUS and i with riot shields even though we were complying and credentialed. I think this might be @letsgomathias ? Would love if someone can confirm. pic.twitter.com/eLUqrNwQBI

— Phoebe Leila Barghouty (@PLBarghouty) May 31, 2020

Alzo Slade, a Vice journalist who was detained for 45 minutes and fingerprinted for being out after curfew even after officers reviewed his press credentials, points out that if you are a black man, being a journalist makes no difference. When cops cornered he and his film crew and made them lie on the ground, it didn’t matter that they immediately identified themselves as press.

“[Of] four people in our crew, three are black men. Growing up in America, we know if we are to reach for anything besides the sky there’s a signifiant chance we get beat up or shot at.” That, he says, should give pause for thought. “The way we were being treated is nothing … In terms of what people are in the streets angry about, that pales in comparison.”

The reason why we are where we are today is because visual [footage] captured what happened to Floyd

Barbara Davidson

If journalists and citizens can’t even attend a protest and safely record from their phones, what happens to truth? “The reason why we are where we are today is because visual [footage] captured what happened to Floyd,” says Davidson. “The police understand the power of visuals right now, and they don’t want the visuals – at least not ones that show them acting abusively.”

For her, the frightening part is that she thinks twice now about reporting on a sticky situation; she has to weigh whether staying out past curfew is worth a rubber bullet to the head. Nevertheless, the case for continuing their work is clear. “If you have nothing to hide, you would not be afraid of journalists or people with cellphones standing and recording you,” says Ou.

In this moment, being able to do their work freely is proving harder than ever.

“Right now, I don’t know how to act, when the very act of bearing truth and just being a witness is now interpreted as a political statement or seen as taking a side,” says Ou. “That’s difficult – because the only side we should take is truth.”