'Thank God Zhou Guanyu's family isn't going through what ours did – it's why dad fought for the halo'

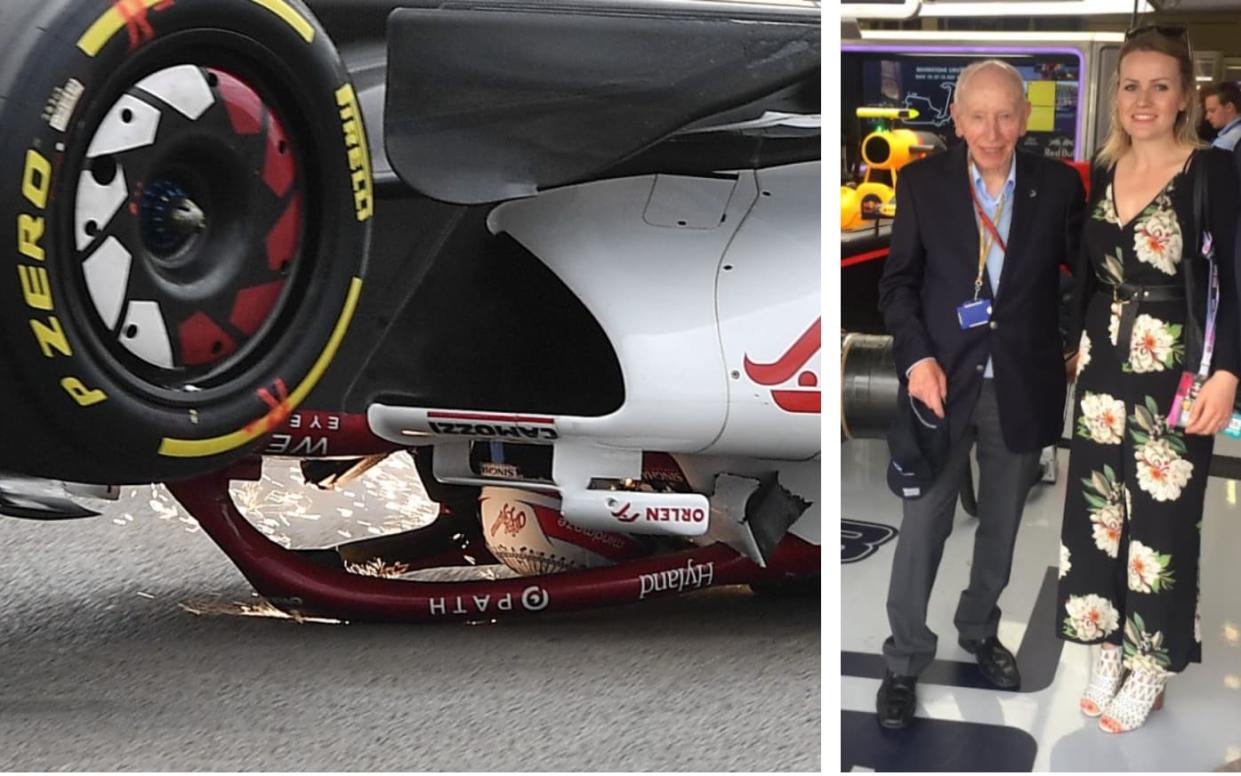

So sickening was Zhou Guanyu’s upside-down crash at Silverstone, and so chilling the wait for any update on his condition, that Leonora Martell-Surtees was contemplating whether to leave the circuit early. As the daughter of the great John Surtees, the only man ever to win world championships on both two and four wheels, the sight of the Chinese driver’s shattered Alfa Romeo triggered hideous flashbacks.

It was on July 19, 2009, that her younger brother Henry, racing in Formula Two at Brands Hatch, had been killed in a freak accident, when the wheel of a rival car, having broken its tether in a high-speed spin, bounced back across the track and landed on his head. Leonora, having endured an agonising wait that day before receiving the worst possible news, had no desire, amid the initial swirl of doubt over Zhou’s fate, to be reacquainted with the memory.

“It was horrifying, to say the least,” she reflects, the day after. “I was finding the accident difficult. We were thinking, had he been injured, we might potentially leave the race.”

She had been watching from the grounds of the British Racing Drivers’ Club, alongside her husband Rich, at the heart of Silverstone’s vast human sprawl. “I have to say that at first we, like most people, didn’t really know what was going on. But anyone who follows motorsport understands, the moment they stop showing the replays, that the crash has been pretty gnarly.

“We had noticed, in the background of the starting grid shot, the car shoot off to the side. The fact that we were all left with nothing being said, and a red flag, we were really worried that Zhou was seriously injured, or that we were looking at a fatality. Having had such a traumatic experience with Henry’s accident, we had decided that we might go. It was a difficult situation. Inevitably, it all comes flooding back.”

Ultimately, Leonora, now 33, can be glad she stayed. For this unforgettable British Grand Prix brought not a repeat of the tragedy that befell her brother, but a stirring affirmation of her late father’s tireless campaigning in honour of his son. Zhou did not perish, instead staging such a staggering escape that, within an hour of being pinned in the wreckage between a tyre barrier and a steel fence, he was seen talking calmly with his team. The rookie owed his survival, he acknowledged, to the halo – an innovation for which Surtees had long agitated.

Asked what he would have made of such a scene, unthinkable amid the lethal dangers that he faced in F1 throughout the 1960s, Leonora does not hesitate. “My dad would have been very, very thankful that things had moved on,” she says. “Even just a few years ago, this crash probably wouldn’t have been survivable. Dad would have been grateful that neither Zhou’s parents nor his family were having to deal with this on a personal level. Yes, these are sportspeople and we put them on a pedestal, but fundamentally, they are someone’s child, someone’s partner. Thank God his family isn’t having to go through what ours did. There’s relief on all fronts that we have seen progress.”

Henry’s death inflicted devastation upon the Surtees family. At 18, he was living up to a daunting paternal inheritance with distinction, holding his own in the feeder series for F1. That a life so rich in promise should be ended by the impact of a loose wheel, his car just finding itself in the wrong place at the wrong time, was an unbearable cruelty. “He was my best mate as well as my son,” a bereft John once said. “He was a golden boy.” And yet he channelled his anguish into lobbying for improved safety at the highest levels of motor racing, desperate to persuade a sceptical sport of the virtues of the halo.

“It’s miraculous that a driver can have such a horrendous accident and survive – and I think everyone can see that the halo must have played a huge part in that,” Leonora says. “What I do know, from the time when my dad was supporting the halo, was that he was very frustrated at how much pushback there was from the industry. It was primarily about aesthetics, but also the aerodynamic aspect. Dad felt angered. He thought that if there had been other people in his position, with what had happened to Henry, they would never had said the same. We’ll never know if Henry had survived, had the halo been in place on his car. But there was obviously a good chance, given the type of accident it was.”

Surtees was exasperated when, in 2016, Lewis Hamilton claimed he would have nothing to do with the halo. “This is the worst-looking modification in F1 history,” he wrote on Instagram. “I appreciate the quest for safety, but this is Formula One, and the way it is now is perfectly fine.” He later deleted the message. Against the backdrop of his shattering loss, Surtees found Hamilton’s remarks irresponsible, arguing that the halo was an essential intervention.

“That’s the key thing I remember, how passionate Dad was about it, how much he was trying to urge people in the industry to support it,” Leonora says. “He was desperate for any measures that would push safety forward. I recall a real frustration that it took so long for people to get on board. Undeniably, it has been such a great addition in terms of safety.”

Indeed, Hamilton can count himself as one fortunate to be alive thanks to the halo. At Monza last year, Max Verstappen’s Red Bull was launched in the air off a sausage kerb, eventually falling on top of his Mercedes. Only the halo saved him from grave injury or worse as he ducked down in the cockpit. It was the same for Charles Leclerc, who had a memorable reprieve at Spa in 2018 after Fernando Alonso’s airborne McLaren descended violently on his Sauber. The device’s greatest moment, though, came at Silverstone on Sunday, when it rescued two drivers in four hours: first F2’s Roy Nissany, then Zhou.

“When Dad was racing in the sixties, one of the main reasons drivers died was due to fire,” Leonora points out. “It would have been catastrophic for Zhou had there been any kind of fire. But safety has come on so much, and this was a massive factor in him not being more severely injured.”

For several years, Leonora ran the Henry Surtees Foundation alongside her father, raising over £1 million for causes from air ambulance services to wheelchair rugby. Last summer, sadly, she had to wind it up – a consequence of both the pandemic and the death, in 2017, of the inspirational John. “Losing the momentum that Dad created was huge for us,” she explains. “I oversaw things with him, but he was very much the figurehead. It was a challenge to continue without him. So much good had been done, the worst thing we felt could have happened was to let it peter out, becoming a shell of what it had been. We didn’t feel that would be a fitting tribute to Henry.

“There’s always more you can do – more causes, more projects. It’s neverending. Unfortunately, the donations aren’t neverending. But we’re proud of what we were able to do. We worked with almost every air ambulance across the UK, increasing the blood they had on board, improving the survival rates of those involved in serious road accidents. That’s at the acute end. But we also kept rugby central. Henry loved rugby. I know that, had he survived the accident but been injured, wheelchair rugby would have been an option. We always tried to think, “What would Henry have wanted?”

At Silverstone, Henry was once more at the forefront of Leonora’s mind as Zhou’s distressing ordeal played out. Except this time, in an abiding testament to John Surtees and his steadfast belief in the halo’s capacity to transform motorsport, there was a different outcome. “I’m just so relieved that someone else doesn’t have to experience what we did,” Leonora says, firmly. “This time the halo was there, doing its job.”