Tributes to 'justice done' as Yugoslav war crimes court closes

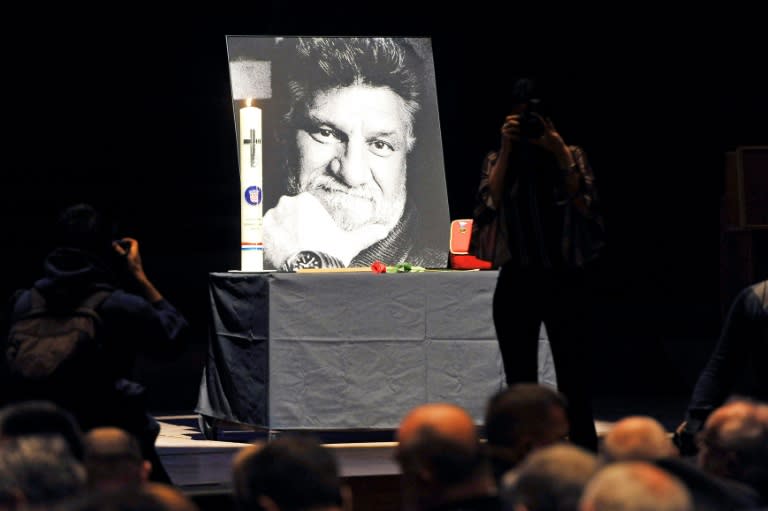

Tributes flowed Thursday to mark the end of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), whose groundbreaking work brought to justice those behind the worst atrocities in Europe since World War II. It has heard more than 4,650 witnesses tell their stories. Its judges have sat for more than 10,800 days and read some 2.8 million pages of transcripts. And now after 24 years with 161 people indicted for their roles in the 1990s Balkans wars -- all of whom have had their cases dealt with -- the ICTY is shutting its doors. "Beyond these numbers, the tribunal gave a voice to victims," UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres told a closing ceremony in the imposing Hall of Knights in the centre of The Hague. And he saluted the courage of the witnesses, such as a boy who crawled over bodies to survive the 1995 massacre Srebrenica and a girl who was repeatedly raped, for their courage in testifying, saying "reliving such horrors takes tremendous fortitude." For the court's last registrar, John Hocking: "After the ICTY, justice is no longer a question of if. It is a question of when and how." "The ICTY set the bar. Now let us raise it higher," he said, pointing to continuing suffering such as the atrocities being committed against the Rohingya in Myanmar. "Let us demand justice where it is still denied. Where it seems impossible." - 'Justice became reality' - At the beginning when the court had no staff and no accused, "justice seemed improbable," Hocking told the guests, who included Dutch King Willem-Alexander. "Yet accused after accused, leader after leader, saw their day in court. Until there were no fugitives left and justice had become a reality," Hocking said. Established by a UN resolution in 1993 at the height of the inter-ethnic fighting, the ICTY was the first international war crimes tribunal set up since the Nuremberg trials after WWII. It painstakingly gathered the evidence to put former Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic on trial, even though he died in his cell in The Hague in 2006 before judgement could be handed down. In many ways, the court helped write the history of the conflicts, establishing the facts of what happened on the ground amid the death throes of Yugoslavia as fell apart after the collapse of communism. And some of the biggest perpetrators who once rained terror on the region -- Radovan Karadzic, Ratko Mladic dubbed the Butcher of Bosnia, Zdravko Tolimir -- have been tried and handed long prison terms for crimes including the Srebrenica genocide. Ninety people, including top politicians and military leaders who devised cruel, inhumane schemes to carve the disintegrating country up along ethnic lines have been sentenced -- some to life in prison. Nineteen were acquitted, 13 had their cases referred back to domestic courts, and 37 others either died or had their cases withdrawn. A retrial of two others, former Serbian spy chiefs Jovica Stanisic and Franko Simatovic will be heard at the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT), which is mopping up the final legal cases including the Karadzic and Mladic appeals. But the ICTY is closing under a cloud. In its final judgement on November 29, former Bosnian Croat military commander Slobodan Praljak, 72, committed suicide swallowing cyanide as his 20-year term for war crimes against Bosnian Muslims was upheld. The incident is being investigated by Dutch authorities, while the ICTY's own probe is due to be published before the end of the month. It was a shocking illustration of how the court's work has been bedevilled by lingering tensions in the region, where many continue to question its authority. - Exceeding expectations - Yet legal experts agree the ICTY leaves a legacy of unparallelled work in writing international jurisprudence, setting a gold standard for future prosecutions in other deadly conflicts. "The ICTY was a resounding expression of international resolve to fight against impunity and for human dignity," said judge Carmel Agius, the tribunal's last president. In a poignant moment, Serbian actress Mirjana Karanovic sobbed as she read out harrowing testimony from some of the witnesses who had helped bring their persecutors to justice. Chief prosecutor Serge Brammertz acknowledged the court's legacy "looks different depending on the perspective you adopt." But he insisted the court was closing with "a credible record that exceeds even the most optimistic expectations." The international community now "recognises that transnational justice is an essential element in peace-building and conflict prevention," he said.